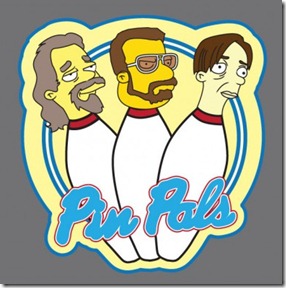

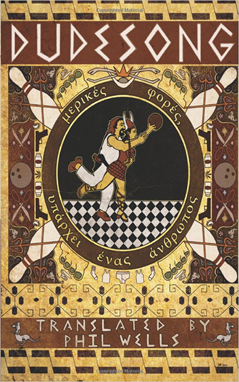

The book Dudesong was written as translation of the screenplay of The Big Lebowski into a mock-heroic form. The book itself is at face value a plain translation but closer study reveals that there is a deep influential connection to a long history of poetry. Not only is Dudesong a brilliant showcase for poetic ability and knowledge, but also has philosophical value for understanding the story of The Dude and Dudeism. The book itself is about 250 pages of iambic pentameter rhyming couplets in the mock-heroic form, with few exceptions. Through conversation with the author the depth of this book’s connection to poetry was made apparent and readily made available an understanding of its meaning. Poetry is utilized as a way to perceive the story of The Dude in a new way that shows the values of the character that otherwise went unnoticed.

Phil Wells is 30 years old and currently lives in New Jersey. He attended the New Jersey Institute of Technology and works primarily as a computer software tester. His writing career generally comes secondary to his work with computers since today writing alone doesn’t pay the b ills very well. Dudesong is the second self-published work from Wells after a collection of essays, poems and sketches entitled “Try the Veal.” Phil Wells also mentioned that his first publication was primarily things he found interesting and funny at the time, but not so much anymore. He keeps a blog that was inspired by the work of Dorothy Parker and her ability to quickly go from serious to comedic tones. Wells also has a heavy influence from Robert Frost since a young age and noted him as the first poet that he first started analyzing critically. Wells’ writing career currently consists of editing a literary journal of short stories and has the idea of beginning a novel. (Wells, Interview)

ills very well. Dudesong is the second self-published work from Wells after a collection of essays, poems and sketches entitled “Try the Veal.” Phil Wells also mentioned that his first publication was primarily things he found interesting and funny at the time, but not so much anymore. He keeps a blog that was inspired by the work of Dorothy Parker and her ability to quickly go from serious to comedic tones. Wells also has a heavy influence from Robert Frost since a young age and noted him as the first poet that he first started analyzing critically. Wells’ writing career currently consists of editing a literary journal of short stories and has the idea of beginning a novel. (Wells, Interview)

Defining a heroic, especially a mock-heroic (or mock-epic), must be accomplished before any argument that Dudesong acts as a mock-heroic can be made. The most accurate definition given by the Oxford English Dictionary is listed as the third adjective form of the word: “a. Relating to or describing the deeds of heroes; of a poem or poetry = epic; so heroic poet. b. Of verse or meter: Used in heroic poetry. In Greek and Latin poetry it was the hexameter; in English, German, and Italian, the iambic of five feet or ten syllables; in French, the Alexandrine of twelve syllables. c. Of the style or language used in heroic poetry; magniloquent, grand;  hence, high-flown, exaggerated.” (OED Online, “heroic”) The definition of a mock-heroic is therefore a “Burlesque imitation of the heroic style in literature; a mock-heroic verse, poem, etc.; imitation of the character, manner, or actions of a hero, esp. for humorous effect.” (OED Online, “mock-heroic”) Dudesong was not originally inspired by the screenplay of The Big Lebowski, but rather the inspired form of The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope happened to fit this story perfectly. (Wells, Interview) The author also commented that Robert Dryden was influential in his motivation to try to take on something of the epic form in metered verse. The definition of a mock-epic from poetryfoundation.org is extremely appropriate in this regard: “A poem that plays with the conventions of the epic to comment on a topic satirically. In Mac Flecknoe, John Dryden wittily flaunts his mastery of the epic genre to cut down a literary rival. Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock recasts a petty high-society scandal as a mythological battle for the virtue of an innocent.” (Poetry Foundation, “mock-epic”)

hence, high-flown, exaggerated.” (OED Online, “heroic”) The definition of a mock-heroic is therefore a “Burlesque imitation of the heroic style in literature; a mock-heroic verse, poem, etc.; imitation of the character, manner, or actions of a hero, esp. for humorous effect.” (OED Online, “mock-heroic”) Dudesong was not originally inspired by the screenplay of The Big Lebowski, but rather the inspired form of The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope happened to fit this story perfectly. (Wells, Interview) The author also commented that Robert Dryden was influential in his motivation to try to take on something of the epic form in metered verse. The definition of a mock-epic from poetryfoundation.org is extremely appropriate in this regard: “A poem that plays with the conventions of the epic to comment on a topic satirically. In Mac Flecknoe, John Dryden wittily flaunts his mastery of the epic genre to cut down a literary rival. Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock recasts a petty high-society scandal as a mythological battle for the virtue of an innocent.” (Poetry Foundation, “mock-epic”)

The idea of Dudesong being a parody to the film The Big Lebowski is entirely accurate and adds perspective to what makes a story “epic.” Phil Wells commented on this idea of a parody in conjunction with the way meaning is perceived, “Dudesong is a parody in the modernist sense that it uses a well-known pastiche to convey another, unlikely, well-known narrative. But Don Quixote was a parody, too. Even The Big Lebowski itself is a genre parody of the gumshoe detective story. It occurred to me as I was writing that putting the film in the context of an epic poem makes the statement "the poet thinks this story is epic." And really, that’s similar to the message people get when they see a Lebowski religion. "These people think The Dude is sacred." Is the message being stated earnestly? In both cases it’s sort of a profound "well, kinda." The joke is that someone translated Lebowski into a religion or a book-length poem at all. The result can be sublime or just an extension of the punchline. It’s

The idea of Dudesong being a parody to the film The Big Lebowski is entirely accurate and adds perspective to what makes a story “epic.” Phil Wells commented on this idea of a parody in conjunction with the way meaning is perceived, “Dudesong is a parody in the modernist sense that it uses a well-known pastiche to convey another, unlikely, well-known narrative. But Don Quixote was a parody, too. Even The Big Lebowski itself is a genre parody of the gumshoe detective story. It occurred to me as I was writing that putting the film in the context of an epic poem makes the statement "the poet thinks this story is epic." And really, that’s similar to the message people get when they see a Lebowski religion. "These people think The Dude is sacred." Is the message being stated earnestly? In both cases it’s sort of a profound "well, kinda." The joke is that someone translated Lebowski into a religion or a book-length poem at all. The result can be sublime or just an extension of the punchline. It’s  in the eye of the beholder.” (Wells, Interview) There are many ways to interpret works such as “Don Quixote” but the factors that make it both a comedy and a tragedy is part of the ironic presentation that Dudesong is also trying to achieve. Anything in the mock-heroic form is a parody on the traditional heroic form and the evidence of influential works like Don Quixote, The Rape of the Lock, and MacFlecknoe shows that this parody narrative form of a mock-heroic can be influential. Wells also mentioned how Dryden’s translation of the Aeneid into metered verse was inspiration to translate The Big Lebowski. (Wells, Interview)

in the eye of the beholder.” (Wells, Interview) There are many ways to interpret works such as “Don Quixote” but the factors that make it both a comedy and a tragedy is part of the ironic presentation that Dudesong is also trying to achieve. Anything in the mock-heroic form is a parody on the traditional heroic form and the evidence of influential works like Don Quixote, The Rape of the Lock, and MacFlecknoe shows that this parody narrative form of a mock-heroic can be influential. Wells also mentioned how Dryden’s translation of the Aeneid into metered verse was inspiration to translate The Big Lebowski. (Wells, Interview)

The comparison of The Rape of the Lock to Dudesong is mostly centered on the reaction of society to what are ultimately trivial things. In Pope’s work the lock of hair cut at a party is a huge scandal that envelops the lives of all the nobles in the poem. Based on a real-life event, Pope found the situation so hilarious that he decided to write the poem in a mock-heroic narrative to reveal the both the social attitude towards the matter as well as a joke on the gossip of the noble class. (Wells, Interview) Wells was inspired by something so trivial and comedic put into a heroic narrative that he wanted to find some way to translate a more contemporary story into the same narrative. The recurring images of fairies and demigods in Pope’s poem directly influenced the recurring images of angels in Dudesong. (Wells, Interview) The opening to Dudesong contains angel imagery right away in its introduction:

The comparison of The Rape of the Lock to Dudesong is mostly centered on the reaction of society to what are ultimately trivial things. In Pope’s work the lock of hair cut at a party is a huge scandal that envelops the lives of all the nobles in the poem. Based on a real-life event, Pope found the situation so hilarious that he decided to write the poem in a mock-heroic narrative to reveal the both the social attitude towards the matter as well as a joke on the gossip of the noble class. (Wells, Interview) Wells was inspired by something so trivial and comedic put into a heroic narrative that he wanted to find some way to translate a more contemporary story into the same narrative. The recurring images of fairies and demigods in Pope’s poem directly influenced the recurring images of angels in Dudesong. (Wells, Interview) The opening to Dudesong contains angel imagery right away in its introduction:

Take heed before our minstrels star to play;

Some thoughts about the city of L.A.

The angels, this metropolis their home,

Kick tumbleweeds around the streets they roam.

(Dudesong, p. 3)

Even the setting of Los Angeles is a part of the comedy of the story because in the screenplay the “City of Angels” is found to contain just the opposite.

Further comparisons can be made to “epic” works such as Dante’s Divine Comedy when in the Dudesong introduction Wells writes:

Be stupefied as I begin to tell

Just how The Dude precipitously fell

And played the hero climbin’outta Hell.

(Dudesong, p. 4)

The heroic motif is extremely present in these three lines not only through vivid imagery, but also through adding a third rhyming line within a work made up of rhyming couplets. Wells also uses a massive amount of abbreviated language which appeared to simply be a method for forcing words into iambic pentameter until the inspiration from “The Rape of the Lock” was revealed. Wells commented that “the heroes of the form had set the precedent” (Wells, Interview), which he found very useful for writing in this form. An example from Dudesong of this would be something like “This guy roll’ng into place in Dude’s front nook.” (Dudesong, p. 28) This can be compared directly to a line from The Rape of the Lock that abbreviates the same way: “O say what stranger cause, yet unexplor’d.” (Pope, The Rape of the Lock: Canto 1)

The heroic motif is extremely present in these three lines not only through vivid imagery, but also through adding a third rhyming line within a work made up of rhyming couplets. Wells also uses a massive amount of abbreviated language which appeared to simply be a method for forcing words into iambic pentameter until the inspiration from “The Rape of the Lock” was revealed. Wells commented that “the heroes of the form had set the precedent” (Wells, Interview), which he found very useful for writing in this form. An example from Dudesong of this would be something like “This guy roll’ng into place in Dude’s front nook.” (Dudesong, p. 28) This can be compared directly to a line from The Rape of the Lock that abbreviates the same way: “O say what stranger cause, yet unexplor’d.” (Pope, The Rape of the Lock: Canto 1)

The idea of The Dude as a hero is another aspect of the comedic function of his role relative to society. The beginning of the movie is a narrated introduction to The Dude and makes the turn to ask “what makes a hero?”, to which the narrator (the Stranger) concludes is The Dude simply because “he just fit right in there” and was “the man for his time and place.” The story after this is entirely about The Dude so it would make sense that his character was written to be this parody of the traditional hero. (Wells, Interview) The archetypal hero that older texts emulate is not the same type of “mock hero” that The Dude portrays. Many of the characteristics in this type of hero are extremely metaphysical and/or unrealistic in real ity. The idea of this “mock hero” is to put a character in the same narrative of a traditional archetypal hero but has the underlying comedic tone. This tone is important because The Dude’s dedication to his own mindset (Abiding) is the reason that the story began in the first place. His sense of “fairness” and wanting to just restore balance by getting his stolen area rug back is what starts a spiral that sends him on many wandering paths. All the while this idea of Abiding and staying genuine to his own morals is what makes him the hero in the end. The irony is that simply wanting a rug back that was stolen due to a sense of fairness is the heroic aspect of The Dude. (Wells, Interview) This is the mock aspect of this story’s heroism because it plays on the expectation that a hero is someone who does something extraordinary when The Dude simply is himself caught in different types of situations all in the name of trying to restore balance to his life.

ity. The idea of this “mock hero” is to put a character in the same narrative of a traditional archetypal hero but has the underlying comedic tone. This tone is important because The Dude’s dedication to his own mindset (Abiding) is the reason that the story began in the first place. His sense of “fairness” and wanting to just restore balance by getting his stolen area rug back is what starts a spiral that sends him on many wandering paths. All the while this idea of Abiding and staying genuine to his own morals is what makes him the hero in the end. The irony is that simply wanting a rug back that was stolen due to a sense of fairness is the heroic aspect of The Dude. (Wells, Interview) This is the mock aspect of this story’s heroism because it plays on the expectation that a hero is someone who does something extraordinary when The Dude simply is himself caught in different types of situations all in the name of trying to restore balance to his life.

Phil Wells also uses changes in meter to give a sense to the context of the scene. He mentions that in the acid flashback scene he makes a direct meter-for-meter, rhyme-for-rhyme parody of TS Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. (Wells, Interview) Wells wrote this portion in a way that slips from five feet in a line to seven, appropriately giving this part of the story a songlike feel. This change of meter reveals a change of perspective in the narrative of the story as well acts remain genuine to the actual music happening in the movie. Phil Wells mentioned that this metrical change-up give the sense of “reality warping a little” (Wells, Interview) by warping the way the music of the poetry sounds to the reader:

Phil Wells also uses changes in meter to give a sense to the context of the scene. He mentions that in the acid flashback scene he makes a direct meter-for-meter, rhyme-for-rhyme parody of TS Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. (Wells, Interview) Wells wrote this portion in a way that slips from five feet in a line to seven, appropriately giving this part of the story a songlike feel. This change of meter reveals a change of perspective in the narrative of the story as well acts remain genuine to the actual music happening in the movie. Phil Wells mentioned that this metrical change-up give the sense of “reality warping a little” (Wells, Interview) by warping the way the music of the poetry sounds to the reader:

While the angels danced his pain and flashbacked drugs.

Then all at once a million stars were scattered in the black.

The strains of Dylan’s “Man In Me” came slowly playing back.

(Dudesong, p. 71)

In fact, Wells considered doing the entire book in septameter but found that it had too much of a “sing-songy” feel to the overall story. Even though the book is a type of song, thus the title Dudesong, Wells and I agreed that iambic pentameter is the most pleasing to the modern way of speaking English. Wells mentioned that “we’re conditioned by pop music to expect measures of four, and septameter feels like 7 beats and 1 rest.” (Wells, Interview) He thinks that septameter should work out fine, but it doesn’t. Neither of us could really come to a conclusion as to why this may be, but the conditioning to hear in even groups is an interesting phenomenon.

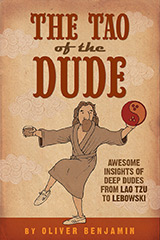

Dudesong was not written with the religion of Dudeism as part of its motivation and there are no intentional connections made by the author. Needless to say it is connected to Dudeism in some form, even if just by its approval from Abide University Press and/or the foreword by The Dudely Lama Reverend Oliver Benjamin. Dudeism is a religion that was founded after the making of The Big Lebowski and is characterized by the figure of The Dude. On the Dudeism website the religion is loosely defined: “Life is short and complicated and nobody knows what to do about it. So don’t do anything about it. Just take it easy, man. Stop worrying so much whether you’ll make it into the finals. Kick back with some friends and some oat soda and whether you roll strikes or gutters, do your best to be true to yourself and others – that is to say, abide. Incidentally, the term “dude” is commonly agreed to refer to both genders. Most linguists contend that “Dudette” is not in keeping with the parlance of our times.” (What Is Dudeism?) Many people commonly mistake this way of life for laziness and do not realize that basic responsibilities do not diminish, only excess stress does. The official philosophy of Dudeism is still very much incomplete and is being constantly refined. The basic connection is to “Abide” in the sense that The Dude did in The Big Lebowski, not necessarily emulating his character the way it portrayed. Abiding is to take a certain perspective on life that a person makes that is in harmony with their minds and the world around them, and never straying from the path of equilibrium. Imagery and method is taken from The Big Lebowski but is not the foundation of what the steadfastness morality necessitates.

Dudesong was not written with the religion of Dudeism as part of its motivation and there are no intentional connections made by the author. Needless to say it is connected to Dudeism in some form, even if just by its approval from Abide University Press and/or the foreword by The Dudely Lama Reverend Oliver Benjamin. Dudeism is a religion that was founded after the making of The Big Lebowski and is characterized by the figure of The Dude. On the Dudeism website the religion is loosely defined: “Life is short and complicated and nobody knows what to do about it. So don’t do anything about it. Just take it easy, man. Stop worrying so much whether you’ll make it into the finals. Kick back with some friends and some oat soda and whether you roll strikes or gutters, do your best to be true to yourself and others – that is to say, abide. Incidentally, the term “dude” is commonly agreed to refer to both genders. Most linguists contend that “Dudette” is not in keeping with the parlance of our times.” (What Is Dudeism?) Many people commonly mistake this way of life for laziness and do not realize that basic responsibilities do not diminish, only excess stress does. The official philosophy of Dudeism is still very much incomplete and is being constantly refined. The basic connection is to “Abide” in the sense that The Dude did in The Big Lebowski, not necessarily emulating his character the way it portrayed. Abiding is to take a certain perspective on life that a person makes that is in harmony with their minds and the world around them, and never straying from the path of equilibrium. Imagery and method is taken from The Big Lebowski but is not the foundation of what the steadfastness morality necessitates.

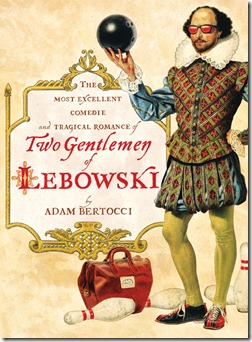

The connection to Dudeism and Dudesong in the poetic sense is quite profound from my perspective. In a phenomenology class I have taken at Gonzaga University the concept of looking at the world “poetically” was explained in “Being and Time” by Martin Heidegger. Having this perspective allows a person to have a more authentic experience with the world around them and allows the things interacted with to reveal a given perception instead of an imposed perception. This is a key method to moving past the solipsism of saying that nothing in the world is fundamentally true. On the contrary, embracing the idea that everything is fundamentally true not only allows us to more openly experience, but also to not have a negative mindset of the universe. The implications of Dudesong to Dudeism in this sense are quite profound because it is literally possible to experience The Big Lebowski poetically. This isn’t to say that this is the only or the first rendition of the screenplay; there is a book called Two Gentlemen of Lebowski: A Most Excellent Comedie and Tragical Romance by Adam Bertocci that is a similar project as Dudesong but uses Shakespearean form instead. The intricacies that Phil Wells put into Dudesong as a mock-heroic reveal a long history of poetry as well as the screenplay itself. With every connection to meaningful literature such as The Rape of the Lock, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock and more the story of The Dude is given to the reader with all of these meanings through poetry.

The connection to Dudeism and Dudesong in the poetic sense is quite profound from my perspective. In a phenomenology class I have taken at Gonzaga University the concept of looking at the world “poetically” was explained in “Being and Time” by Martin Heidegger. Having this perspective allows a person to have a more authentic experience with the world around them and allows the things interacted with to reveal a given perception instead of an imposed perception. This is a key method to moving past the solipsism of saying that nothing in the world is fundamentally true. On the contrary, embracing the idea that everything is fundamentally true not only allows us to more openly experience, but also to not have a negative mindset of the universe. The implications of Dudesong to Dudeism in this sense are quite profound because it is literally possible to experience The Big Lebowski poetically. This isn’t to say that this is the only or the first rendition of the screenplay; there is a book called Two Gentlemen of Lebowski: A Most Excellent Comedie and Tragical Romance by Adam Bertocci that is a similar project as Dudesong but uses Shakespearean form instead. The intricacies that Phil Wells put into Dudesong as a mock-heroic reveal a long history of poetry as well as the screenplay itself. With every connection to meaningful literature such as The Rape of the Lock, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock and more the story of The Dude is given to the reader with all of these meanings through poetry.  Discussion with Rev. Oliver Benjamin helped to shed some light on how the form of Dudesong is important: “the mock epic – that is precisely what The Big Lebowski is, and yet in the same way that we’re discussing the parody/not parody aspects of the film, it is both mock and not-mock. I would venture to say that other great works – Quixote, Moby Dick, Ulysses (what i call "litherature" because they are milestones, monolithic signposts on the highway of our long cultural road) also fall into this category to some degree.” (Benjamin, Interview) Even if Dudesong falls short of being something like this the story of The Dude does not. Dudesong should become a milestone at least for Dudeism and its understanding of the story and perhaps further study will help Dudeists to attain a more profound understanding of their own morals.

Discussion with Rev. Oliver Benjamin helped to shed some light on how the form of Dudesong is important: “the mock epic – that is precisely what The Big Lebowski is, and yet in the same way that we’re discussing the parody/not parody aspects of the film, it is both mock and not-mock. I would venture to say that other great works – Quixote, Moby Dick, Ulysses (what i call "litherature" because they are milestones, monolithic signposts on the highway of our long cultural road) also fall into this category to some degree.” (Benjamin, Interview) Even if Dudesong falls short of being something like this the story of The Dude does not. Dudesong should become a milestone at least for Dudeism and its understanding of the story and perhaps further study will help Dudeists to attain a more profound understanding of their own morals.

Overall, this project gained complexity the more in depth I went into it. For something that is regarded as a parody this would seem rather rare. Because the experience of this story became richer with poetic study at the same time as my studying Heidegger and the philosophy of interacting with the world “poetically”, I began to realize that this book could have incredible value to the religion of Dudeism (of which I am an active member). It would seem as if the connections made in this paper are only scratching the surface of the value hidden inside of this book and the idea of a mock-hero and I do not plan to stop my investigations here. I would like to personally thank the author Phil Wells for his time and profoundly helpful discussions. I would also like to thank Reverend Oliver Benjamin for connecting me to Phil Wells, for his enthusiasm for the project and for his assistance with understanding Dudeism.

Dudesong can be obtained for a modest fee via Amazon.com and elsewhere.

I love the references to balance and equilibrium in this article as they apply to Poetry, to Life, and to Dudeism. Balance is so Key. In fact, I’ve heard that to have a good sense of Humor means having a good sense of Proportion.

Thanks for the kind words, govna! I didn’t necessarily think in terms of equilibrium when I wrote this but I definitely tried to approach this from all angles possible. I also very much agree with your last statement.