By Rev. Oliver Benjamin

There is a persistent romantic myth that children are born innocent and become evil only after becoming socialized, though anyone who clearly remembers their early childhoods knows in their heart that this is not so. Against the evil genius of children, we are all of us in the gutter.

There is a persistent romantic myth that children are born innocent and become evil only after becoming socialized, though anyone who clearly remembers their early childhoods knows in their heart that this is not so. Against the evil genius of children, we are all of us in the gutter.

And so it was with me as well. I already suffered a sufficiently dorky first name, but even my last name was seized upon. They called me “Benjamin Franklin,” and though he was a great revolutionary hero with an unsurpassed genius, all I could see as an eight-year old was a short, fat, elderly, bespeckled bald man who dressed like an old woman.

Thankfully, now that I am grown I have a new perspective on my near-namesake. And not only because I too am short, fat, myopic and balding now, but because I have finally discovered what a cool guy he was. This year, three hundred years after his birth, a series of celebrations and exhibits have brought old Ben back into cultural currency, and I’m not just referring to hip-hop artists calling the US 100-dollar bills that bear his visage “Benjamins.” Alas, if only hip-hop had been around when I was a boy.

Franklin’s emerging re-popularity stems not only from his storied accomplishments, but from his successful cultivation of personal virtue. In our modern world of often plastic, ignoble and unworldly leaders, a man like Benjamin Franklin would be cooler than the Clintons, even more eloquent than Obama, and far more with it than any given Bush.

Franklin’s emerging re-popularity stems not only from his storied accomplishments, but from his successful cultivation of personal virtue. In our modern world of often plastic, ignoble and unworldly leaders, a man like Benjamin Franklin would be cooler than the Clintons, even more eloquent than Obama, and far more with it than any given Bush.

Admiring the scope of Franklin’s life is a bold task in itself – the man accomplished more in his 91 years than some entire countries. His printing business was essentially the first US media conglomerate, allowing him to retire at 42 and devote his life to living (and thinking) large. In that period he brought down Promethean fire from the heavens in the form of electricity, provided cheap heating with his Franklin stove, set up numerous charities for workingmen’s benefit, and played a pivotal role in securing American independence by obtaining war funding from the French. He brought us the postal service and the library. Not least, he was also famously successful with the ladies. This is a fact that should not be lost on those who invoke his name in today’s rap music, nor should his skillful facility with words – a great deal of our most-beloved popular sayings can be attributed to Franklin.

There’s no arguing it: Benjamin Franklin was cool. Equal parts intellectual, humanitarian, voluptuary, successful businessman, artist, cosmopolitan, and cad, he was exactly the type of post-renaissance man the modern world is now looking for. Compared to him, James Bond is a dilettante, Arnold Schwarzenegger is a eunuch, and Mother Theresa was a shameless self-promoter.

Admittedly, we’re a long way from recreating a man from a strand of DNA. So until someone creates Neoclassic Park, how can we cultivate more Frankliness in our own lives? Probably the easiest way to learn Franklin’s secrets is to read his autobiography. Sadly, condensing his own enormous existence proved too much of a task even for him, and so he was never able to complete it. Still, it is the most accurate map we have of his mind and methods – the accounts of others were normally either superficially fawning or acerbically jealous. It seems that only a man of Franklin’s potent humility and reason could accurately measure his own mythic stature. It’s a good read, too, and by some estimations the best-selling autobiography of all time.

Admittedly, we’re a long way from recreating a man from a strand of DNA. So until someone creates Neoclassic Park, how can we cultivate more Frankliness in our own lives? Probably the easiest way to learn Franklin’s secrets is to read his autobiography. Sadly, condensing his own enormous existence proved too much of a task even for him, and so he was never able to complete it. Still, it is the most accurate map we have of his mind and methods – the accounts of others were normally either superficially fawning or acerbically jealous. It seems that only a man of Franklin’s potent humility and reason could accurately measure his own mythic stature. It’s a good read, too, and by some estimations the best-selling autobiography of all time.

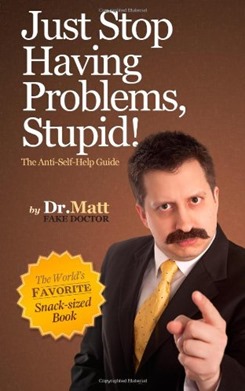

It’s a shame, because the lessons are of timeless value. One section of his autobiography in particular contains an ingenious practical step-by-step plan for nothing less than acquiring what Franklin called “moral perfection,” and what we in the post-Tony Robbins age, leery of using such a loaded term like “morals” might call “personal power.” But in fact, he created the plan with the bold expectation that becoming perfect was possible, and that he would be one to find the way. You’ll need to read the autobiography yourself to see how it turned out, but the plan still stands. Franklin admits that he had intended to publish this section as a small book in its own right. Called simply “The Art of Virtue,” it would be a guide that told you not only what to do, but how to do it.

Had Franklin written the section today in the simple, direct and cozy prose of Dr. Phil, he’d probably have a self-help bestseller on his hands. But elaborate sentences like “I concluded, at length, that the mere speculative conviction that it was our interest to be completely virtuous, was not sufficient to prevent our slipping; and that the contrary habits must be broken, and good ones acquired and established, before we can have any dependence on a steady, uniform rectitude of conduct” would be unlikely to win over a talk-show host or studio audience.

Had Franklin written the section today in the simple, direct and cozy prose of Dr. Phil, he’d probably have a self-help bestseller on his hands. But elaborate sentences like “I concluded, at length, that the mere speculative conviction that it was our interest to be completely virtuous, was not sufficient to prevent our slipping; and that the contrary habits must be broken, and good ones acquired and established, before we can have any dependence on a steady, uniform rectitude of conduct” would be unlikely to win over a talk-show host or studio audience.

Which brings to mind a question that has bothered me ever since I tried to study Shakespeare in High School: Why is it that a book written in outdated and difficult English prose can be freely translated into simple, lucid Spanish or Chinese but not into modern, easily-readable English? Imagine, for instance, how nice it would be for students to understand implicitly that “wherefore art thou Romeo” actually means “why do you have to be who you are” and not the commonly erroneous “where the hell are you?” To disallow a contemporary adaptation is to fall in love with the mothballed manuscript, not the ideas it contains. But this would be regarded as simple desecration by lovers of the English language and its statuesque saints.

Luckily today we have something old Ben would have been absolutely besotted with: The Internet, a rabidly democratic publishing house of ideas and speculation, categorically free from the controls of kings, civil servants, and tenured bureaucrats. In fact, the Web is chock-a-block with amateur “Poor Richards” churning out all varieties of almanacs, both rich and poor, preposterous and sublime. Finally, one needn’t press any presses to print an easy translation of The Art of Virtue – it already exists.

Glen Norris, its creator, seems to have accumulated his own fair share of Frankliness. According to his website he was involved early on with the first CD-ROM publishing outfits, traveled the world, set up the first human rights website (to help oppressed minorities in Burma), wrote a book, started a telecommunications company based in the Philippines, invented 3D telephony (with a portfolio of patents), P2P micro-charity, and doles out regular contributions to online poetry compendiums. One little known project is the concise, easily-accessible version of The Art of Virtue, available as a free pdf file from his website.

Glen Norris, its creator, seems to have accumulated his own fair share of Frankliness. According to his website he was involved early on with the first CD-ROM publishing outfits, traveled the world, set up the first human rights website (to help oppressed minorities in Burma), wrote a book, started a telecommunications company based in the Philippines, invented 3D telephony (with a portfolio of patents), P2P micro-charity, and doles out regular contributions to online poetry compendiums. One little known project is the concise, easily-accessible version of The Art of Virtue, available as a free pdf file from his website.

Norris’ rendering is often comically laid-back. For example, Franklin’s circuitous “that hard-to-be-governed passion of youth hurried me frequently into intrigues with low women that fell in my way, which were attended with some expense and great inconvenience, besides a continual risque to my health by a distemper which of all things I dreaded, though by great good luck I escaped it” is now simply “I don’t party too much. I must say, I did sow my wild oats, but thank Goodness it didn’t become a way of life.” Straight up, Ben Franklin.

Though the phrasings are reinterpreted, the content is all Franklin’s including his reasoning for how he came up with it. Importantly, the ingenious system of acquiring virtue is unchanged. In it, Franklin identified after lots of pre-internet reading and research, a certain thirteen virtues and decided to concentrate on each of them for an entire week. He devised a weekly chart enumerating virtues in a clever attack plan. And he used that plan, improving it through the years, for the rest of his life.

Though the phrasings are reinterpreted, the content is all Franklin’s including his reasoning for how he came up with it. Importantly, the ingenious system of acquiring virtue is unchanged. In it, Franklin identified after lots of pre-internet reading and research, a certain thirteen virtues and decided to concentrate on each of them for an entire week. He devised a weekly chart enumerating virtues in a clever attack plan. And he used that plan, improving it through the years, for the rest of his life.

In crafting this simple method, Franklin beheld in literal black and white the evolving quality of his own character, and boldly intended that others might try as well. This is assuming, of course, that said virtues are agreed upon and that the moral resolve to attain them is in order, otherwise the chart would likely reveal only a pointillist selfie or dubious morality.

Taken into consideration all that’s changed in the last centuries, it might justifiably be up to the individual to accept or reject any or all of the virtues as given. Chastity might not be the average college student’s cup of tea, and frugality might not endear itself to an ascendant Hollywood luminary. In keeping with Norris’ spirit of modernization, entirely new, more timely virtues might be inserted – maybe drive carefully, or be nicer to waiters or even eat less carbs. Nevertheless, when it comes to inculcating self-discipline, it couldn’t hurt to err on the side of the old fashioned. Allow dead and distinguished Ben his props.

A key feature to Norris’ version is the ability to print it out as a small booklet so that you can keep it with you at all times. Print. Cut. Fold. Voila! One can only imagine how Ben might exult: America’s first self-improvement book, conceived by her first great publisher, finally sees its way into paper and pocket. Even Franklier, it’s practically free – allowing a new perfection pilgrim to put some points on the board right away, specifically, in the frugality column.

A key feature to Norris’ version is the ability to print it out as a small booklet so that you can keep it with you at all times. Print. Cut. Fold. Voila! One can only imagine how Ben might exult: America’s first self-improvement book, conceived by her first great publisher, finally sees its way into paper and pocket. Even Franklier, it’s practically free – allowing a new perfection pilgrim to put some points on the board right away, specifically, in the frugality column.

I’m on the program and in the third week in my quest for virtue. Week one, or temperance, was relatively easy, though Friday and Saturday both received black dots, though week two, silence, proved a challenge due to the fact that I play in a rock band. Nevertheless, the very fact that I’m writing this article is a direct consequence of this week’s cardinal goal, order. See, I’ve been planning to write this article ever since seeing Ben’s original manuscript in a museum but it became increasingly submerged in the back pages of my disorganized life. Thanks Ben and Glen, for impelling me to dig it out.

And so cheers to you, Benjamin Franklin, from a guy who shares one of your names and perhaps some small, but increasing, measure of your virtue, and with fresh marks in the gratitude column.

~ Note: This was originally written in 2006. It’s been edited and updated a bit. Some anachronisms may persist. ~

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.