Todd Alcott, one of the esteemed contributors to our very own Lebowski 101 has allowed us to republish his good and thurrah analysis of the Coen Brothers’ latest masterpiece, Inside Llewyn Davis. There are a lot of ins and outs to this movie, but Todd has produced the deepest and most comprehensive analysis out there.

Before we meet Llewyn Davis, we get a title card; “The Gaslight Cafe, 1961.” The location and date are important. The Gaslight Cafe was one of the hubs of the folk-music revival scene in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s-early 1960s. That scene is primarily known today for producing Bob Dylan, the most brazenly talented American songwriter of his generation. Dylan is an important shadow cast over the narrative of Llewyn Davis, but, more important, the whole Macdougal Street scene and its attendant joys, sorrows and contradictions, inform the shape of the narrative, which I’ll do my best to discuss as we move forward.

So we meet Llewyn onstage at the Gaslight, singing a song onstage. The song is “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” by Dave Van Ronk. Now, the reader should be aware, that when a song like this is “by” someone, in this venue, what that generally means is that the singer-songwriter has built on a much older song, sometimes a song that has been through a dozen previous permutations. In the case of “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” it’s based on a much older song called “I’ve Been All Around This World.” The point I want to make here is that “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me, at first glance, as sung by the bearded hipster Llewyn Davis with no introduction, seems a little bit pretentious. Is this guy, the viewer wonders, really equating himself with a condemned man? “Poor boy,” he croons in the refrain, implying that his hanging is unjust, that he’s been persecuted by a big monolithic political machine. The point of this stance, in its time, was to connect the sophisticated hipsters of the gritty city to the darker corners of ancient American life. There was, and is in this scene, an air of disingenuousness: what could someone like Llewyn know about the troubles of the unjustly-persecuted rural poor from a hundred years or more before? There has always been the air of the worship of the “noble savage” in the stance of the modern folk singer: all those songs about working the land, wandering the back roads, being hunted and wronged, cruel judges and princes and queens. The singer always seems so far removed from the situation. The folk singers of the Gaslight in 1961 were trying to revive and re-define a deep strain of Americana. In a way, the narrative of Llewyn Davis asks “Does Llewyn deserve to sing these songs?” That is, is he really the “poor boy” he claims to be, or is he a pretentious hipster?

(In some ways, Llewyn is a saddened sequel to O Brother Where Art Thou?. That movie was about these exact same songs, revived just thirty years earlier, at a time when the preservation of Americana was a pressing concern. O Brother was about the “Old, Weird America,” an America before global consumerism kicked in, when there were still pockets of “real people” to be found. Llewyn takes those same songs and places them at another crossroads, at the point where they were about to explode into the popular consciousness, just when they were about to become mass culture, consumer products. In some ways, the Greenwich Village folk scene succeeded well beyond its intentions: it took the songs of the people and handed them over to the corporations.)

So there is Llewyn onstage, singing his ancient song of poverty and persecution. Is he a poser, an archivist, a revivalist? Or is he an artist?

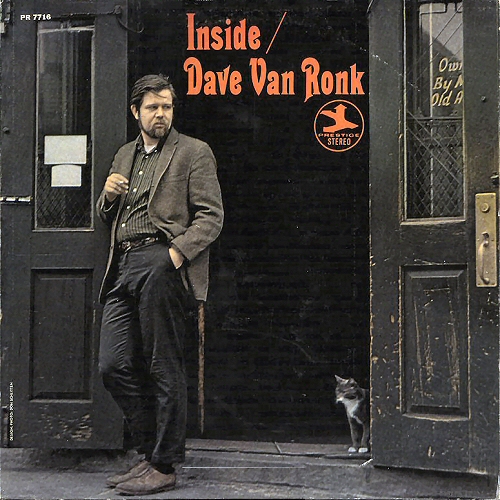

It’s been bandied about that the character of Llewyn is based on Dave Van Ronk, “The Mayor of Macdougal Street,” a mainstay and centerpiece of the Greenwich Village folk scene. This is nonsense. Llewyn shares one or two biographical details with Van Ronk, but has none of his personality. More importantly, he has none of Van Ronk’s expansiveness, his desire to reach out, to promote, to connect. Llewyn is a very inward singer, up in his own head. He demands that the audience comes to him. That demand, in fact, is, I think what the protagonist wants. Llewyn Davis wants success, craves it, but insists that it be on his own terms. Like Bob Dylan (and the movie will continue to draw comparisons to Dylan), Llewyn refuses, absolutely refuses, do do what is expected of him.

Which brings us back to folk music. At a time when the Cold War reigned, when the shadow of nuclear apocalypse hovered over New York, when a hard rain very much threatened to fall, why did hipsters reach into the guts of American music? The movie being discussed never raises the specter of the nuclear shadow, it keeps the folk scene a show business phenomenon. The hipsters of Llewyn Davis sing folk music not because it speaks to them or because it connects them to their roots, but because there is a market for it.

That’s an important distinction. Because the next thing that happens to Llewyn is that he goes out to the alley behind the Gaslight and gets his clock cleaned by a lean, angry Southerner. The man sucker-punches Llewyn in a paroxysm of righteous fury. We don’t yet know who this telephone-pole of vengeance is, and the Coens shoot the scene with dispassionate observation, but we gather that Llewyn has misbehaved toward this man’s wife, “caused a scene” at his expense. Like the folk songs of old, the movie will come back and repeat this scene, and at that point we’ll know what it means, and when that meaning is revealed, then we’ll know what the movie is about.

To put yesterday’s question differently, “authenticity” is a key concept in Llewyn Davis. Who is authentic, who is not, who “means it” when they perform music, and who is faking it, who is willing to prostitute his or her talents for the sake of commerce, and who is not. Authenticity wasn’t an issue in O Brother Where Art Thou, the songs performed belonged to everybody. “Old-Timey Music” was a pop-culture fad of the day, and it was used as both a commercial and political tool, but it also rose up out of the very soil under the characters’ feet. The songs of O Brother were being sung whether anyone was listening or not. No such freedom is put forth in Llewyn Davis — all the songs (but for one crucial exception) exist on the commercial stage.

(The subject of American musical authenticity is a tricky one. A while back I read an article in the New York Timesabout how there is evidence to suggest that Robert Johnson, the King of Delta Blues Guitarists, enjoyed playing pop songs and show tunes in his live sets, but recorded his protean blues numbers “because there was a market for ‘race’ records” at the time. If Robert Johnson was motivated by commerce to sing the blues, then there is no authentic blues voice — it’s all show business. Which is also the subject of Llewyn.)

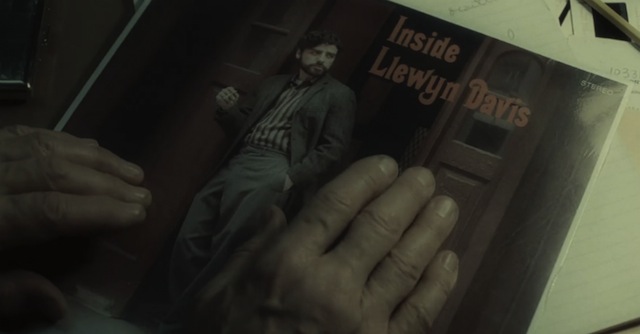

The movie doesn’t tell us, but after Llewyn gets punched by the mysterious Southerner in the alleyway behind the Gaslight the narrative begins. We’ve just seen the end of the movie, now we’re going back to the beginning. The movie doesn’t tell us that, of course. There is no title card that says “Three Days Earlier” or anything. Rather, the movie plays with that doubt. Llewyn wakes up in someone’s apartment on someone’s couch with someone’s cat sitting on his chest, and this all seems to be part of his routine. He makes himself at home, he strums his guitar, He makes himself some eggs, he peruses the apartment’s artworks and record collection. He finds a copy of his own record, the one he made with his partner, the Timlin and Davis album If We Had Wings.

He drops a needle on the record and listens to himself and his partner singing. The song is titled “Fare Thee Well,” but folk-song aficionados know it as “Dink’s Song.” And, as this song comes to be fairly important to the narrative, it behooves me to discuss it.

“Dink’s Song” was first noted (by folk music aficionados) in 1908. John Lomax (father of folk music aficionado Alan Lomax) heard it sung by a black woman in Texas, singing it as she washed her clothes by a riverside levee-building camp. It is called “Dink’s Song” because the only thing John Lomax knew about the woman singing it was that she was called “Dink.”

So for the purpose of our analysis, let’s say that Dink qualifies as “authentic.” Here is a woman, singing as she washes her clothes, for the purposes of we don’t know what — keeping a rhythm, passing the time, entertaining herself, expressing herself, whatever. Let’s set aside for the moment the idea that Dink is singing “to impress the ethnomusicologist.” If Dink is “authentic,” singing from the heart for no commercial purpose whatsoever, what does that make Timlin and Davis? They may be champions, they may be preservationists, they may be motivated by celebration and joy, but they are still singing “Dink’s Song” for money, for a commercial end. However gorgeous and heartfelt their recording is, and it is, it’s not authentic. They don’t know, and cannot know, Dink’s life. (Assuming “Dink’s Song” actually begins with Dink, and not from some earlier source, which is a dumb assumption to make.) The narrative of the song is one of loss: the singer has lost a loved one and now cannot go home. Well, everyone has lost a loved one, and people in their 20s often can’t go home for a variety of reasons, so the song is certainly singable by a wide variety of folks. But has Llewyn felt the kind of loss the song implies, and can he go home? And if he cannot, why not? Again, as with “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” the narrative will slowly unfold the answers to those questions.

Llewyn leaves a note on the sideboard: “I was a sorry mess last night.” Because of the previous sequence, we think he’s referring to getting punched in the alleyway. On a second viewing, we realize that Llewyn apparently apologizes for being a mess every goddamned morning. (The notepad gives us the location of the apartment, near Columbia University, and the job of the lessee, a professor in the sociology department. For those unfamiliar with New York geography, Columbia University is at the opposite end of Manhattan from Greenwich Village. And, for the young, it was once possible for downtrodden artists, even folk singers, to live in Greenwich Village in 1961.)

But he’s about to make a worse mess. As he leaves the apartment, the cat gets out and the door locks behind him. And, since this is the Coen Bros, there’s a good bet that the cat “means” something. Let’s say for now that the cat symbolizes “responsibility,” and that Llewyn’s handling of the cat is a mirror of how he handles his other responsibilities. Because, if nothing else, Llewyn is really bad at handling responsibilities. First he tries to fob the cat off on a neighbor (who isn’t home) and then the elevator man (who refuses), then tries to contact the owner (a Professor Gorfein) but gets only his secretary. He gives the secretary a message, “Llewyn has the cat,” which gets repeated back to him as “Llewyn is the cat.” So maybe the symbolism of the cat isn’t that difficult to parse: the cat is Llewyn, Llewyn is the cat.

Considering, however, that Llewyn and the cat end up having markedly different character arcs, maybe Llewyn is notthe cat. Or, keeping in mind the last time the Coens contemplated a cat in one of their movies (ie Schroedinger’s cat in A Serious Man), maybe Llewyn is the cat and is not the cat at the same time. In any case, the cat will turn out to be okay, in part, the narrative suggests, because, unlike Llewyn, it pays attention to its surroundings. It watches out the windows of the subway train as it rushes from Columbia University down to Greenwich Village. We don’t know it, but the cat, unlike Llewyn, has plans to make it home.

Llewyn takes his cat, or rather the Gorfein’s cat, to a friend’s apartment in the Village, drops it off with a saucer of milk and goes to see the guy in charge of his label, Legacy Records. Legacy Records does not seem to be a huge operation. It has, apparently, two employees, Mel and Ginny, both witheringly old. Their office is a mess, they can’t find anything; this is not a high-powered recording company. Llewyn, we learn, is not selling records, and didn’t really sell records when he was part of a duo act either. He doesn’t even have a winter coat (a detail inspired by this record cover).

What does Mel want? Is Mel a marginal chiseler keeping money from his hard-working charges, or is he just barely scraping by himself? It’s difficult to say. Mel seems closely related to any one of the many characters from A Serious Man, he is both things at once. On the one hand, he brushes Llewyn off as a pest, on the other hand he offers him a winter coat. When Llewyn calls Mel on his bluff, Mel gets angry: is he actually angry with Llewyn, or is his anger just part of the bluff, a way to keep his money and his winter coat? Is Mel a good-hearted loser who believes in his sad-sack acts, or is he a penny-pinching miser tone-deaf to commercial trends and incapable of selling an act? He scolds Llewyn for being rude, but then gives him forty dollars. Either the forty dollars is a small percentage of what he owes Llewyn (which other characters later hint at) and/or he’s being generous with an act he considers a friend.

Llewyn makes his way back to his friend Jean’s apartment. Jean is furious, first about the cat, then about being pregnant. (In a movie filled with songs, and plot points, about unborn or missing children, it’s tempting to believe that the cat, unnamed as it is, stands in for one, or all, of those missing children. Which is another way of saying that Llewyn himself is a missing child.) Llewyn is hoping to crash at Jean’s for the night, but finds that his place has been taken by a young soldier named Troy. Troy, it seems, is the exact opposite of Llewyn: a soldier instead of a bohemian, naive instead of streetwise, patriotic instead of cynical, enthusiastic instead of world-weary. The one thing they have in common is that they’re both folk singers. Troy, in fact, is singing at the Gaslight later that night.

(The Gaslight, it occurs to me, also turns up in The Hudsucker Proxy, with Steve Buscemi tending bar. Bob Dylan, who, like the Coens, is a Minnesota Jew, turns up on the soundtrack to The Big Lebowski and, my favorite, as the unspoken punchline to a joke in The Ladykillers, when Irma P. Hall makes a reference to a civil-rights event being attended by “a Jew with a guitar,” a line spoken as though “a Jew with a guitar” was as wondrous and as absurd as a pig with wings.)

Troy sings his number at the Gaslight (“The Last Thing on My Mind” by Tom Paxton — a tiny bit anachronistic, since Paxton wouldn’t record it until 1964). It is, once again, a tale of lost love, of sorrow and separation — none of the songs on the Llewyn Davis soundtrack have happy endings, or even rousing choruses. The word most of them share is “Farewell.” (With one wicked exception, which we’ll get to soon.) Troy holds his own at the Gaslight, much to Llewyn’s bafflement and dismay. Jean’s boyfriend Jim shows up and confirms the audience’s opinion: “Wonderful performer,” he gushes, “Wonderful.”

Llewyn takes the opportunity to ask Jim for money to pay for an abortion. He doesn’t mention that the girl who needs the abortion is Jim’s own girlfriend Jean. Jim can’t do it, he couldn’t give Llewyn money for “another” abortion without telling Jean.

Up on stage, Troy finishes his number to warm applause. (Oddly enough, “finger snapping” is not represented in this movie, even though the Gaslight is where the cliched beatnik habit took root: the upstairs neighbors of the Gaslight complained about the noise, forcing the audiences to find a quieter way of expressing their appreciation.) He begins to ask “someone special” to come up and join him on stage, and Llewyn rolls his eyes. He can’t stand to be called upon to perform, certainly not by the likes of a straight-arrow loser like Troy. His consternation is misplaced: Troy asks Jim and Jean to come up instead, leaving Llewyn doubly insulted. Now he’s been overlooked by a straight-arrow loser.

(Llewyn keeps the entire world at arm’s length, but has he earned his weariness, or is it all just a pose? As someone remarked recently, Llewyn’s primadonna behavior would be forgiven if he were a genius, but he’s not a genius. He’s doing all the things Bob Dylan did at the same time – sleep on people’s couches, skulk through the streets of NYC with a guitar on his back, break hearts and be a jerk – but he doesn’t have Dylan’s magnetism and raw talent. In a way, Llewyn’s problem may be that he loves folk music too much to sully it, whereas Dylan started sullying it early on, cannibalizing it for its raw elements and spinning them into pop gold. If Llewyn had become successful, would he have also “gone electric,” or would he have been one of the ones jeering Dylan that fateful day?)

Onstage, Troy, Jim and Jean sing “Five Hundred Miles,” another song of painful separation, this time about a lonely railroad man who is too ashamed of his poverty to come home. Llewyn, we will learn, is also poverty-stricken, but need he be? He seems to have chosen his path when easier paths were laid before him. (There is also the matter of the not-talked-about breakup of his duo act, which we’ll get to later.) The song is a big hit in the room, everyone in the club seems to know it and sings along, much to Llewyn’s dismay. Pappi, the club’s owner, plops himself down next to Llewyn and says “That Jean. I’d like to fuck her.” His profanity sticks a sharp needle into the glowing balloon of the trio’s performance, and we feel violated that he’d bring such a base show-business attitude to such purity. But then Llewyn nods and says “Uh-huh,” and we realized that he, too, thought the exact same thing the first time he saw Jean onstage. If Jean is the purity of folk, Pappi is the music industry ready to make folk its bitch.

The morning after Troy performs to such acclaim, Llewyn wakes up on the floor of Jim and Jean’s apartment. Normally, he would have slept on Jim and Jean’s couch, but his place has been given to Troy. Now, Llewyn is woken by the sound of Troy eating breakfast cereal, sitting straight back on a rocking chair, the bowl in his hands. “Well that was very good,” he remarks after finishing his simple meal: the tiniest pleasures are a cause for reflection in Troy’s world.

“What’s next?” says Llewyn. “Do you plug yourself in somewhere?” Llewyn sees the guileless Troy as a machine, a robot, a tool of the military-industrial complex. Troy (a Trojan horse?) sets Llewyn straight on that tip: he’s in the army for the discipline, but he’s getting out in a few months and is going to become a folk singer. He mentions one Bud Grossman, a club-owner and big wheel who has expressed interest in representing Troy. Every Coen Bros movie has its head guy, the guy from whom all power flows, and Bud Grossman is this movie’s. Bud Grossman (whose name mean, literally, “big man”), we gather, has “cracked the code” of making a living off of Folk music. He has his club, The Gate of Horn (which was a real club in Chicago), which, the reader will not be shocked to learn, has roots in Greek mythology. There are two gates, one of horn and one of ivory, through which dreams pass. The gate of horn produces “true” dreams, and the gate of ivory produces “deceptive” dreams. A nightclub called The Gate of Horn, then, would be a place where one would go to hear the truth, as expressed through dreams, which is what songs (and movies) really are. So Bud Grossman, we gather, will be a final arbiter of truth and deception. He likes Troy, and therefore we gather that Troy represents truth, at least for Bud Grossman.

But for now, the point of the scene is that Troy has taken his youth and invested it in a craving for discipline, which is one thing Llewyn has decidedly not done. A self-styled artist, Llewyn has to “feel” it or else he can’t abide it. And if his path hurts or offends, that’s the offended party’s problem. The one creature he feels any responsibility toward is the Gorfein’s cat, who, when Llewyn opens the window to have a cigarette, dashes out of and vanishes into the great city. Llewyn is more upset about the cat getting lost than he is about Jean’s unborn child. Perhaps because the cat sort of is Jean’s unborn child, or perhaps another of Llewyn’s unborn children, all those potential lives out there, just as Troy is a potential version of Llewyn.

Llewyn takes Jean out to Washington Square Park to talk about her pregnancy. The headline of the scene is “Jean Does Not Like Llewyn.” “You should not be in contact with any living thing,” she hisses. She so regrets having sex with him that she would rather abort her pregnancy than risk the chance that the baby might be Llewyn’s. We’re reminded that Llewyn has been down this road before, with a “Diane,” and “knows a doctor.”

After Jean’s anger is somewhat spent, she says “I miss Mike.” Mike, the reader will recall, was Llewyn’s old singing partner. The tone in Jean’s voice suggests that perhaps she was in love with Mike, and perhaps had sex with Llewyn because he reminded her of him. Perhaps they both missed Mike, and spent a night together to comfort each other. For that matter, the death of Mike may be the inciting incident of Llewyn’s downfall, although he seems to have had plenty of personality issues before that event. In any case, Mike, dead as he is, has made the genuine final farewell, that one gesture that clearly separates the authentically pained from the posers.

So who is Llewyn Davis? Where does he come from? Does he, like Dylan (and the Coens), come from the bleak, rugged land of the north Midwest, land of farms and iron?

Nope, he comes from Queens. Which is where he goes now, to visit his sister. Does he love and miss his sister? Nope, he goes to her house to see if she has any money. Their parents’ house has apparently sold, and he’s hoping to get some of the money from that.

Llewyn looks down on his sister, whom, he feels, has “sold out,” joined the ranks of middle-class losers who live merely to “exist.” Llewyn’s father, now in a nursing home, is one of those “existers.” Now that Llewyn’s sister has sold their father’s house, Llewyn wants the money to fund his show business career, but at least he’s not merely “existing,” which for him would be a death sentence. This is a fairly typical attitude for Llewyn, he looks down on all the people he mooches from.

Llewyn’s sister has a gift for him: a box of his belongings from the old house (obviously, Llewyn has left dealing with the father completely to her). In the box are his merchant marine papers (which will become important later) and an acetate of a record Llewyn made when he was eight, “Shoals of Herring.” Llewyn tells his sister to put the box “out on the curb.” Like Dylan, and many of the NYC folk scene, he’s seeking to reinvent himself, shed himself of his middle-class background and become a mysterious, urban-bumpkin folk star.

Llewyn calls Mitch Gorfein to lie about the whereabouts of his cat, then hustles over to Columbia Records, where Jim, the boyfriend of the woman he may have impregnated, is having a session for a novelty song, performing, with a handful of other musicians, as “The John Glenn Singers.” Columbia is the belly of the beast for Llewyn, the heart of commercial recording. The halls of Columbia are as cold, stark and empty as a mausoleum, the dead opposite of the digs at the Gaslight. The song they’re there to record is called “Please Mr. Kennedy,” and it’s as close as Llewyn Davis comes to addressing current world events. But this novelty song isn’t about the Cold War, the nuclear shadow or civil rights. It’s a song about the most optimistic of Cold War issues, the space program. Llewyn is shocked to learn that fellow folkie Jim wrote this throwaway ditty; the mere fact of it, in Llewyn’s eyes, disqualifies Jim from any sense of “authenticity.”

Jim, of course, is merely filling a niche in the marketplace. There is money to be made in the music business and he’s figured out how to do that. Llewyn has not, although he certainly feels entitled to it. The recording of “Please Mr. Kennedy” is the moral fulcrum of Llewyn Davis: as the record producer stares down, gimlet-eyed, from his glass tower, Jim and his band of folk minstrels jump through their hoops to make a silly record. That’s the state of the music industry in the winter of 1961: the Beatles haven’t happened yet, and John Hammond hasn’t yet discovered Bob Dylan. Young musicians are performing monkeys, producing nonsense for cash, striving to get a foothold on a whirling merry-go-round. Llewyn gives the recording his all, but then rushes out of the session as though afraid he will contract a disease. He takes a flat session fee rather than garner royalties, and makes sure to get a date on one of the backup singer’s couch before the ink on the contract is dry.

(The scene stands in sharp contrast to its equal in O Brother Where Art Thou. In that movie, Ulysses and his band of misfits stumble into a tiny recording studio unannounced, record their old-timey number in nothing flat for a clearly delighted producer, and take off with their money, masters of their destiny. Llewyn is a hired hand for a brand-new novelty song, the studio is vast, the producer stares at his charges with dollar signs in his eyes and Llewyn, disgusted, signs over his rights to the recording.)

(Faithful reader Curt Holman notes in the comments that “Please Mr. Kennedy” is a burlesque of this song. Not only does this bring up relevant questions of authenticity, but it speaks to a common practice at the time of creating spoof versions (and “answer songs”) of popular numbers, and how those spoof versions sometimes would eclipse the originals. For instance, while many accused Elvis Presley of ripping off Big Mama Thornton with his recording of “Hound Dog,” in fact Elvis was not recording her version. Rather, Elvis’s recording is based on a “spoof version” by a Vegas act, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys. And, of course, with regards to authenticity and the practice of white singers becoming famous by imitating black singers, it’s important to remember that “Hound Dog” was written by Leiber and Stoller, two Jews from the Brill Building.)

Llewyn goes to see his manager Mel. Mel has gone to a funeral, which he apparently does a lot of, not because he needs to but because he enjoys them. In a morbid way, you could say that he’s built a career around it, making his label, Legacy Records, a lifelong funeral for American music. As long as he’s there, Mel’s secretary Ginny gives Llewyn a box of his remaindered albums, the record he recorded with his partner Mike. “What am I gonna do with it?” sighs Llewyn, but he takes it with him anyway. He heads over to the apartment of the backup singer Al Cody. Al dresses like a cowboy and has a box of remaindered records under his end table just like Llewyn’s — clearly, Al has been around the same block as Llewyn, just a beat before.

Llewyn, having worn out his welcome at Jim and Jean’s place, is now without abode. He meets Jean at the Cafe Reggio for a kiss-off date.

“Do you ever think about the future at all?” despairs Jean, after making sure Llewyn has lined up an abortion doctor for her. Llewyn sighs and looks at the ceiling. “You mean, flying cars?” he asks. What Llewyn is trying to say is that “the future,” for him, isn’t something you plan for, that to plan for the future is “careerist.” He thinks of himself as above that. He disowns his past (while trying to mooch off his family) he doesn’t consider the future, he lives “in the now,” which would be admirable if it didn’t take a whole (Greenwich) village to support his artistic freedom.

In the middle of rejecting Jean’s vision of life, Llewyn sees what he thinks is the Gorfein’s cat walking down the street and dashes after it. Like Tom chasing his hat in Miller’s Crossing, Llewyn chases a cat. Tom’s hat was a key part of his identity, but Llewyn’s cat is something else, a symbol of the one shred of responsibility he carries.

Llewyn heads over to Al Cody’s house with the cat, only to learn that he must vacate Al’s apartment, because Al’s girlfriend is coming to visit. Glancing at Al’s Mail, he finds that Al’s given name is Arthur Milgrum. (Not to be confused with Stanley Milgram.) Al, with his cowboy hat, goatee and blue jeans, is no more authentic than Llewyn is. (Al Cody was inspired by Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, another Greenwich Village folkie, who styled himself as a cowboy and was born Elliott Charles Adnopoz in the wild-west town of Brooklyn.)

Llewyn goes to see “his guy,” the doctor who will perform Jean’s abortion. Llewyn’s done business with him before, with Diane, the other girl he got pregnant. He’s surprised to learn that the Diane didn’t go through with the abortion, that she had his child and moved to Akron. That means that Llewyn, the singer of songs about lost love and farewells and separations, has a child out there somewhere in the heart of America. The doctor has not been able to get Llewyn’s money back to him, since “I never see you at the hoots anymore.” He’s referring to “Hootenannies,” which were folk-music open-mic nights at Folk City. Llewyn’s dirty look at the word “hoots” suggests that Llewyn considers himself above such a gathering, that perhaps he’s graduated from such an amateur-hour show or else considers Hootenannies too joyous and free-spirited for such a serious-minded man as himself. Or, perhaps “the hoots” was where he performed with his dead partner Mike, and feels a need to distance himself from that part of himself.

Llewyn takes the cat to the Gorfeins’, and gets invited in for dinner. In the Gorfein’s apartment are some dinner guests, “early music” folks from the Columbia faculty. I’m guessing that the Coens picked Columiba University for its geographical distance from the Village, and not for sharing a name with Columbia Records, although I could be wrong: as the record company appears to be a mausoleum, the university folk appear to be quite humorless about their niche and utterly baffled by Llewyn’s understanding of music. Folk music is about tradition, but the university folk are about “serious music,” the whole idea of music conveying joy is alien to them. (Adding to the Columbian aspect of the scene, Llewyn mentions later that Mr. Gorfein lectures in Pre-Columbian history, a term that cuts at least three ways here.)

And yet, in the very next scene, when the Gorfeins ask Llewyn to play a song at the dinner table, he refuses, in spite of Mrs Gorfein mentioning that “music is a joyous expression of the soul.” Llewyn reluctantly begins singing “Dink’s Song,” self-conscious both because he’s being made to literally sing for his supper, and also because he’s embarrassed to be singing a folk song in front of the snooty-nosed early-music academics. When Mrs. Gorfein begins singing “Mike’s part” of “Dink’s Song,” Llewyn loses it. Mike’s death is apparently still a huge sore spot with him, but he covers his pain by lashing out at the Gorfeins for treating him as an amateur. “I’m a professional!” he yells, “I do this to pay the bills!” Of course, Llewyn hasn’t paid the rent, or the bills, in years – he doesn’t even have an address. So his bellowing about professionalism is mere puffery.

To put an exclamation point on the evening, Mrs Gorfein announces that Llewyn has, in fact, brought to their house the wrong cat. “Where’s its scrotum?!” she wails. A question we might also put to Lllewyn. When will Llewyn grow a pair, so to speak, and face up to his responsibilities?

So Llewyn, for the first time in a while, is now truly homeless, due to circumstances entirely within his control. For the next few days, his home is Al Cody’s car, which is being driven to Chicago by a couple of friends of Al’s. He takes his cat, which is not the Gorfein’s cat and not his cat, in fact we don’t know whose cat it is, and neither does Llewyn. The cat is, currently, just another orphan of the storm of Llewyn’s life. Spoiler alert!

Driving the car is Beat Personified Johnny Five, and in the back seat is old-time Jazzbo Roland Turner. Roland is full of stories, and full of himself, full of the romance of the road and the life of the musician. He’s not stuffy and ascetic like the Gorfeins’ early music friends, and he doesn’t seem to be an urban hick like Al or a striving careerist like Jim. He’s definitely run down though, you can tell that his time in the spotlight has ended. He’s trudging around the museum of his memories now. Is that the future of Llewyn, a fat old has-been with his stories and his condescension and his bum leg and his need for frequent bathroom stops? Is that cost of “authenticity?”

Even though Llewyn just refused to sing for the Gorfeins, he sees nothing wrong with singing for Johnny Five and Roland, even though Roland is asleep and would prefer to remain that way, and Johnny hasn’t said five words since the trip began. Llewyn’s music can be, it seems, anything he wants it to be at any given moment: a precious gift, an expression of the self, a valuable commodity or an impertinent irritant, a jab to the more high-falutin’ music of his elders, almost a proto-punk.

Roland needles Llewyn about the ease of folk, suggesting that it’s not a form for “serious” musicians – that’s his argument for jazz’s “authenticity.” Llewyn then tells Roland (and us) the fate of his partner Mike: he threw himself of the George Washington Bridge. Even that strikes Roland as inauthentic: a real musician, he says, would throw himself off the Brooklyn Bridge. When Llewyn retaliates with a threat, Roland strikes back with a threat of voodoo: one day, he says, “your life will be shit, and I’ll be somewhere laughing my ass off.” And while it’s easy to believe Llewyn’s life will one day be shit (he’s pretty much there already), it’s hard to buy that Roland will be laughing anywhere at all.

While Roland and Llewyn are sleeping, Johnny Five suddenly turns chatty. “Clean Asshole Poems and Smiling Vegetable Songs, Orlovsky,” is his idea of a conversational salvo. He then mentions that he did “Three weeks in The Brig” (even though that play was not produced for another two years). The production was “closed by the cops. Long story.” The short version of the long story, for those interested, was that The Brig offered an intense, no-holds-barred depiction of life in a Marine prison. The show was such a sensation that congressional hearings were called to investigate the events depicted in the show and the theater producing the show was closed. That, the scene seems to suggest, is the price of “authenticity” – you get shut down by the authorities.

That night, at a rest stop, Johnny Five treats his companions to some of his poetry. Johnny seems to be a self-styled Beat, and while Roland appears to like Johnny’s poem well enough, Llewyn is not impressed. The Beats had hit the scene a good five years before the winter of 1961, which to my mind makes Johnny Five a bit of a Johnny-come-lately, an imitator, and thus inauthentic. It’s not authentic to imitate something five years old, it is, however, authentic to sing a song that’s a hundred years old.

Roland excuses himself to use the bathroom, the third time we’ve seen him do so. When Llewyn comes to the men’s room, he finds Roland passed out in a heroin crash: what we thought was a weak bladder is really a bad habit. So we can add “crippling addiction” to Roland’s other “authentic” qualities. And it’s perhaps worth noting that the word “hip” originated with the jazz musicians of Roland’s time, as a term to differentiate between those who used heroin and those who did not. Roland is a portrait of what happens when hip becomes old.

Llewyn’s album, and Dave Van Ronk’s. Complete with cat.

In the middle of the night, outside of Chicago, Llewyn falls asleep in the passenger seat. When he wakes up, the car has stopped and the police are in the middle of arresting Johnny Five. Spoiler alert!

Johnny Five doesn’t take kindly to authority figures. Maybe it’s his affection for the Beats, maybe it’s the time he spent in The Brig, maybe this particular cop is a particular asshole. In any case, Johnny gets whisked away by the police, leaving Llewyn, Roland and the cat stranded by the side of the highway. If Llewyn is a kind of dark sequel to O Brother, then Johnny Five is Llewyn‘s version of Baby-Face Nelson, the trigger-happy bank robber who blows into that narrative like a hurricane and blows out again just as fast, a manic-depressive whirlwind. Johnny Five, like Nelson, has two sides, but instead of manic and depressive, he’s laconic and volcanic, rage with a hair trigger.

In any case, he’s suddenly gone from the narrative, never to return, and Llewyn, an expert escape artist, does not think twice before he abandons the car (which is also his friend Al Cody’s car) with the sleeping, crippled Roland, and the cat who is not the Gorfein’s cat inside. The cat, that last shred of humanity Llewyn had left, is left, literally on the side of the road on a highway somewhere in the darkness of America.

Llewyn hitches a ride to a bus station and then takes a bus into Chicago, leaving Roland and the cat to their own devices. The enormity of this is kind of hard to pass up. He doesn’t even wake up Roland to tell him what’s happened, or attempt to take the cat anywhere. Nor does he try to contact any authority to alert them to the stranded car with the crippled jazz musician and the cat in it. Roland and the cat are just two more pieces of jetsam in Llewyn’s wake.

Where is Llewyn off to in such a hurry? Well, since he didn’t tell us at the top of the act, when he got in the car, he tells us now with his actions: he’s going to go see Bud Grossman at the Gate of Horn, that place where truth is told. Before he can get there though, he needs to rest, perhaps because it’s morning and the club isn’t open yet. In any case, while he’s waiting he gets ejected from a diner by an impatient waitress and then ejected from the train station by an impatient cop. Llewyn doesn’t give the cop any lip, he saw what happened to Johnny Five. He’s got an appointment with destiny (or so he thinks) and he can’t stop to be hassled by the man. He’s got to toe the line.

He gets to the Gate of Horn, which is empty (the gatekeeper is not in attendance) and huge, but the administrator on duty at least let’s Llewyn wait there, out of the Chicago cold. While Llewyn warms up (musically, if not temperature-wise), Bud Grossman, the Great Man, the man who symbolizes the ultimate authority, the man who appears in every Coen Bros movie, Capital, walks in and past Llewyn, without seeing him.

Llewyn gathers his nerve and approaches Bud in his office, as the Great Man struggles to remove his galoshes. Suddenly the Great Man is just another club-owner, struggling to get by on a cold winter’s day. Llewyn introduces himself and reminds Bud that his manager, Mel, has sent him his album. “Oh, you’re with Mel,” says Bud, with a glint in his eye that indicates that Mel is, perhaps, a manager of suckers and losers, the 1960s folk music version of ARK Music Factory. “I was just passing through,” says Llewyn, as though he hadn’t just traveled three days and left his compadres by the side of the road in order to attain this meeting. Turns out, Mel never sent Llewyn’s record to Bud, which means perhaps that Mel’s never really sold any records to anybody. Bud sighs and rolls his eyes as Llewyn struggles to get a copy of his album out of his bag. “Here it is,” his expression says, “Another fucking folk singer from Mel, another poorly-dressed loser with a guitar and a record under his arm.” In spite of Bud’s despair at Llewyn, and in spite of his disdain for Mel, Bud actually steps up. “You’re here, play me something,” he says, game and, under the circumstances, welcoming. “Play me something from inside Llewyn Davis,” he adds, with just a hint of venom in his voice. He seems to doubt that there is, in fact, anything inside Llewyn Davis. From what we’ve been seeing, we’re worried that perhaps he’s right.

Llewyn, who refused to sing for the Gorfeins, then used the opportunity to berate them, then played to Johnny Five and Roland to irritate them, faces a new task: will he, should he, play for Bud Grossman, on demand? Should he be able to put aside his pride and artistic altruism for the sake of impressing Capital, in the hopes of career advancement?

The answer, of course, is “yes.” Because Llewyn, for all his talk of artistic integrity and how advancement is for squares, is still perfectly capable of sucking up to authority, if that authority could launch his career. So Llewyn sits down with Bud on the floor of the Gate of Horn, that place where truth is spoken, and tells the truth. He sings “The Death of Queen Jane,” a song about a woman in a difficult labor. She pleads with her husband, King Henry, to cut her open so that she can be out of pain and that the baby might live. King Henry refuses; he’s worried that the operation might kill both. Because the King cannot choose, the queen dies and the baby lives.

The song has obvious literal relevance for Llewyn, who has one child he doesn’t know and another due to be terminated in a few days’ time. But what other significance might it have? Perhaps Llewyn feels that he is Queen Jane, with a great and precious gift inside himself, willing to die so that the baby might live. Perhaps he feels that he’s King Henry and Queen Jane is his music, and he feels forced to choose between killing the music to save the baby (whatever arises from a career in music) or letting both die. In any case, his performance of this woeful song is definitely sad, bitter and rueful, a real tour-de-force. And Bud Grossman’s verdict is, without question, the most devastating Llewyn could hear: “I don’t see a lot of money here.”

Because, of course, the guardian of the Gate of Horn, where truth is told, is a capitalist. And while Llewyn’s performance of “The Death of Queen Jane” might be a pinnacle of artistic truth, Bud’s verdict is the pinnacle of another kind of truth: there is no place in show business for an artist like Llewyn. And yet, Bud isn’t a heartless businessman: he mentions that he really likes Troy Nelson, the gawky serviceman from Act I. Why? Because “he really connects with people.” Llewyn, both literally and artistically, does not connect with people, he’s a stubborn individualist, albeit an individualist who requires a raft of people to support him and his individualist ways. Bud, in a moment of compassion, even offers to put Llewyn together with a trio he manages (presumably Peter, Paul and Mary, who were created by Albert Grossman and for whom Dave Van Ronk auditioned, and was rejected for being too uncommercial). Llewyn turns Bud down, which, if you know anything about folk music, is a super bonehead move: within a year, Peter, Paul and Mary would be a million-selling group, the spearhead of the folk movement and a skyrocket that would bring Bob Dylan to national prominence with their recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Bud suggests that Llewyn get back together with his partner, not knowing that Llewyn’s partner is dead. “That’s good advice,” says Llewyn, his path now officially cut short. It’s one of the best scenes of the American movie year.

Llewyn, newly discarded from the world of show business, trudges back to New York in this cold, cold American winter.He hitches a ride with a guy going east, driving so the guy can sleep. The guy, who seems to be a regular working-class guy, one of the millions who, in Llewyn’s mind, merely “exist,” trusts Llewyn to handle the situation. Which, in its way, is the saddest joke of the movie.

In the night, on the lonely, bleary American highway, Llewyn first spies a road sign leading to Akron, where his Queen Jane still lives, with his unknown baby. And even though Llewyn has, literally, been given the verdict of death by the Great Man Bud Grossman, he doesn’t take the turnoff and seek to start a new life as a family man. No, he continues back to New York, avoiding responsibility to the last. How much is he avoiding responsibility? Later in the night, dozing at the wheel, the exhausted Llewyn strikes a cat on the road, and leaves without troubling to make sure it’s okay. It may, or may not, be the same cat that he left in the car with the sleeping Roland (it doesn’t look like the same cat, but that’s kind of beside the point at this juncture) but, when choosing between his sleeping passenger and the injured cat, he decides to honor his contract with his passenger and pushes on into the night. Does that represent a step up for Llewyn, morally speaking, or a step down? Or, if “Llewyn is the cat,” has he just struck himself a death-blow, and decided to leave himself limping on the side of the road, the way he’s left so many others?

(For what it’s worth, when Llewyn passes by Akron, the car radio is playing a jazzy rendition of “Old McDonald.” When he strikes the cat, it’s opera. The first is snappy but vulgar, the latter sublime. Does Llewyn consider family life the equivalent of a dressed-up version of a children’s song, but the abandonment of a wounded cat a moment of ironic bliss? That is, is abandoning his responsibilities, even to his own self, an act of low comedy or high drama?)

Llewyn next awakens in his sister’s house. He leaves without a word of goodbye and heads to the local merchant marines office, looking for work. It seems he’s given up, for the moment at least, his artistic ambitions. Unfortunately, he’s behind on his seaman’s dues. “You haven’t paid your dues,” says the administrator, not knowing the half of it.

Llewyn pays up, grumbling “I’m leaving naked, clean start,” as though perhaps the merchant marines represents a kind of grubby new birth, or perhaps a new death, and, before he leaves, goes to visit his father in the old-folks’ home. His father, it seems, is something of a legend in the merchant marines. Everyone speaks highly of him, and there’s a trophy case full of memorabilia about him at the old-folks’ home. Although the place is gray and grim, it seems as though Llewyn’s father was able to make a name for himself and garner the admiration of his peers, which is more than Llewyn can claim now.

Llewyn’s unable to talk to his father, and his father seems unable to listen; either deafness or dementia has claimed him. So Llewyn, for the fourth time in the movie, takes out his guitar to do the speaking for him. This time, he uses it as a kind of plea to connect to his past. He sings “Shoals of Herring,” the song he recorded when he was eight, the song which, back in Act I, he was eager to get rid of. The song is about a life at sea, and a continuum, the old and the young, the yearning to live away from society and become part of a tradition, and it moves Llewyn’s father, but not in the way he’s intending. Rather, it moves only his bowels, and Llewyn has to fetch an attendant to clean up — Llewyn’s music has, literally, moved the shit out of his father.

He goes back to his sister’s house to fetch the papers he needs to sign on to the ship, but that ship, as they say, has sailed — the papers he needs are the same ones he asked his sister to put out by the curb a few days before. In his rush to discard his past, he’s discarded his future.

Homeless and jobless, Llewyn goes once again to Jean, not to stay or even to crash, but just to rid himself of his belongings. Jean, surprisingly, shows a little concern for where Llewyn might stay. Until he forgets when he scheduled her abortion for, that is.

Jean has good news for Llewyn: she’s talked the manager of the Gaslight into letting him play the following night. Llewyn refuses: he’s done with folk singing, ready to start anew as a merchant marine, like his father — his brain-dead, incontinent father. “The Times is gonna be there,” urges Jean, but Llewyn, exhausted by his life of delusions, still refuses. Unfortunately, the merchant marines don’t want him back — he’s got to pay $85 dollars for a new license, money he doesn’t have. So now Llewyn can’t even quit the way he wants to; he has to play if he wants to quit.

That night, with nowhere else to go, he goes to the Gaslight to see the show. This is not the show the Times will be at, that’s the following night. Instead, on the bill tonight are a vocal quartet who sing songs of prison and executions and canals in Auld Ireland. Are the men onstage Irish? They affect the accents, which is a guarantee of nothing: Bob Dylan affected the phoniest-baloney accent ever sliced, and continued to alter his voice to whatever style he deemed appropriate. It’s just show-business.

As if to underscore the point, the Gaslight’s manager, Pappi, sidles up to Llewyn and talks about how Jim and Jean draw a crowd not because they’re talented but because they’re sexy. He then lets slip that he’s “fucked Jean,” although it’s unclear when. When Llewyn asks, Pappi merely shrugs and says “If you want to play the Gaslight…” So either Pappi had sex with Jean in exchange for getting booked at the club, or else she offered herself to him while Llewyn was out of town, in order for Llewyn to get the booking during the all-important Times evening. In either case, that’s the last straw for Llewyn: the Gaslight, what is supposed to be a haven for authenticity, is as corrupt and phony as any Vegas showroom or Hollywood backlot.

So when the quartet introduces the next act, a middle-aged woman from Arkansas named Elizabeth Hobby, Llewyn’s mood is as black as pitch. Mrs. Hobby takes the stage and informs us that this is her first trip to New York, and she’s going to sing a song she grew up with. She’s got an autoharp, that least hip of folk instruments, and is homely and plain, dressed in what an Arkansan might wear to dress up for her first club gig in New York City. “Where’s your hay bale?” jeers Llewyn, “Where’s your corn-cob pipe?” The joke here is that Mrs. Hobby is, in fact, the real deal, one of the “folk” who makes “folk music” what it is. It’s not show-business to her, she loves the music and has sung it all her life. Llewyn, at the end of his rope, has chosen to ruin the debut of a genuine folk artist. He keeps up his jeering until he gets ejected from the club.

The movie does its best to play it down, but that is, in fact, the climax of the narrative: Llewyn has been drawn through the wringer of “authenticity” to the point where he doesn’t know authenticity when he sees it, and, in fact, lashes out at it when it’s in front of him. There is no indication that Mrs. Hobby wants a career in show business or to write jingles or be in TV. She’s unpretentious, not a poser, and rightly horrified by Llewyn’s outburst.

Llewyn goes, one last time, to the Gorfeins’. He’s humbled and deferential to them: he has, perhaps, seen now that, despite their silliness, they’re good people who have welcomed him as family. The Gorfeins’ dinner guests tonight are a couple of middle-aged squares, who have heard Jim’s “Please Mr. Kennedy” song and are delighted by it. That, Llewyn sighs, is the record-buying audience: squares looking for a laugh.

The biggest surprise of the evening, though, is the return of the Gorfein’s cat, whose name is Ulysses. The Greek Ulysses famously took ten years to get home from the Trojan War, but the cat only took a couple of days. (And the Ulysses from O Brother Where Art Thou took about the same amount of time.) If Llewyn is the cat, does that make Llewyn a Ulysses, and does that make the Gorfeins’ apartment his home? And, if a cat can get home from Greenwich Village to the Upper West Side just by memorizing the subway stops during its trip downtown, can Llewyn reach a similar resting place after traveling to Chicago and back, leaving a handful of wrecked lives in his wake?

And here the narrative ends. But of course it doesn’t end, instead it continues where it started, like a reprise of a chorus. Suddenly it’s the beginning of the movie again, not the next day but the day a few days ago, before all this craziness happened. Llewyn is now reborn, a man who needs to sing one more set in order to get the money to ship out for good.

Llewyn leaves the Gorfeins’ apartment for the last time, and we remember that, the first time through this sequence, they showed him playing “Dink’s Song” from his album with Mike. That may be why he chooses to follow “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” with “Dink’s Song” in his set that night at the Gaslight: he’s leaving where he came in. But before he gets to the club, he passes by a theater showing the Walt Disney movie The Incredible Journey (which was not released until 1963). That movie, of course, deals with household pets who, against all odds and reason, cross vast differences to find their home. Ulysses the Greek did that back in The Odyssey, and Ulysses the cat did it over the past few days, but can Llewyn ever really return home? What, in the end, did his journey mean? And where, really, did he get to?

So here we are, back at the Gaslight, on the night the Times is coming, and Llewyn singing “Hang Me, Oh Hang me.” And somehow, as if by magic, questions of authenticity have evaporated. Llewyn, for all his flaws, and they are legion, seems eminently qualified to sing this song of execution and persecution, of hard traveling and dashed expectations. “One more before I go,” he says afterward, leading into “Dink’s Song,” his tie to his own past, to Mike, to lives and loves lost in the American wilderness. “Fare thee well, my honey,” he sings, with genuine force and emotion, not just to his love, but to the audience, his children, show business, everything, perhaps even his life.

Pappi is cheered by Llewyn’s rendition of “Dink’s Song,” because of its association with Mike, who, it seems, was always Llewyn’s better half, and forgives him for the mess he caused in the club the night before. The next act takes the stage, a gangly young man unmistakably Bob Dylan. Dylan starts off his set with a song titled “Farewell,” yet another goodbye song. Is he singing to Llewyn, or is he just another poser, a young man pretending to be world-weary before his time?

As Dylan sings, and the Times is in the crowd listening, and the folk-music world is about to explode into the national consciousness, Llewyn goes out back to receive his beating. The man administering the beating, it turns out, is Mr. Hobby, the wife of the autoharp-strumming naif from the night before. Llewyn watches, aching and bleeding, as Mr. Hobby hails a cab in the street and storms out of New York, never to return. The folk music scene, it seems, is no place for a folk singer. The most often-used word in Llewyn Davis, it seems, is “farewell,” but as Mr. Hobby drives off Llewyn salutes and says “Au revoir.”

This could mean two things, and the Coen Bros, being the Coen Bros, point to neither. The most obvious meaning is that Llewyn is saying good-bye (in a pretentious, mean-spirited way) to the folk scene altogether, and will take his share of the night’s sales and re-join the merchant marines. But another possibility exists: this, remember, is the night the Times has come to the Gaslight, and has, presumably, seen Llewyn sing his electrifying set. We know what happened after the Times came to the Gaslight and saw Dylan: they printed a glowing writeup, which was read by John Hammond, who signed him to Columbia Records, and the course of American music was changed forever. While Llewyn might never attain Dylanesque fame, it’s possible that, like Dave Van Ronk, he might become a genuine folk hero, a champion of the form, “The Mayor of MacDougal Street.” That is, it’s possible that Llewyn, resigned to death is, in fact, on the verge of a re-birth. That the movie ends with this question dangling is its most aching paradox.

[Note: Click on the links to the original parts at his website to see additional comments by Todd’s readers.]

_______

A contributor to Dudeism’s Lebowski 101, TODD ALCOTT is a screenwriter living in Los Angeles. He has a blog, What Does the Protagonist Want?, conveniently located at www.toddalcott.com, where he analyzes screenplays.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.