Introduction

"Now this a-here story I’m about to unfold…"

The Big Lebowski is a 1998 comedic movie by Joel and Ethan Coen which has gone from virtual obscurity to become one of the best-loved films of the subsequent decade. Barely earning more than its modest 15 million dollar budget in the theaters, it’s gone on to generate impressive revenues in DVD sales and rentals, not to mention a huge cult of devoted fans, perhaps rivaled in numbers and enthusiasm only by the venerable Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Describing the film to those unfamiliar with it can be tricky because it generally represents different things to different people. This is certainly of the principal reasons it received such delayed commendation by critics, and why it took so long for audiences to catch on to its charms. Like many great masterpieces (e.g. novels like Melville’s Moby Dick and Joyce’s Ulysses) it works on so many different levels that it generally takes repeated viewings before people "get it" — even if they tend to disagree on what "it" actually is. Furthermore, since the film intentionally plays with (and against) genre stereotypes, expectations are often initially confounded.

Nevertheless, as with most complex pleasures, investing a little time in it can pay off huge rewards. The Big Lebowski is one of those rare movies that can be watched over and over again without ever growing stale. In fact, it’s not unusual for serious fans to have watched it ten times, twenty times, or more, and see something new in it each time.

This article is directed both at established aficionados as well as those who just want to know what all the fuss is about. Out of respect to the latter group, it doesn’t include all the details of the plot. It is not meant to be taken as a detailed overview of every aspect of the film. This in mind, think of it as part review, part overview, part who’s-who, and part celebratory whoo-hoo!

Overview

"A way out west there was this fella, fella I want to tell you about…"

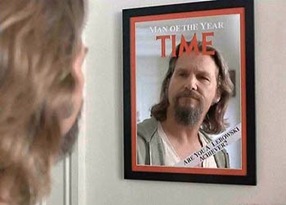

The story concerns one Jeffrey Lebowski (portrayed by Jeff Bridges), a man in his mid-to-late 40s whose life hasn’t amounted to much, at least not by the standards of the early 1990s in which the film takes place. He’s unmarried, unemployed, drives a lousy car, lives in a modest apartment in a run-down part of Venice Beach, a district of Los Angeles, California. He spends most of his days enjoying "bowling, driving around, the occasional acid flashback" and indulges in a steady stream of White Russian cocktails and marijuana cigarettes.

Despite superficial appearances, however, he’s clearly not a "loser." Lebowski appears quite content with his simple, untroubled lifestyle. One might even say he enjoys a certain wisdom, confidence and peace of mind that more "successful" folks might aspire to. Though his attitude is revealed in several ways, the most obvious and immediate is that he fancifully refers to himself as "The Dude." It is a moniker both proud and humble at the same time — he appears to employ it not out of hip self-regard but because it so aptly describes his easygoing outsider persona.

The Dude’s peaceful lifestyle is suddenly compromised at the beginning of the film. Two thugs turn up at his apartment demanding money that they claim his wife has stolen from a man named Jackie Treehorn; one of them even jams the Dude’s head in the toilet to underscore their seriousness. When the Dude finally protests that he doesn’t have a wife ("the toilet seat is up, man!"), the thugs look scornfully around the ramshackle flat and realize that this must not be the Jeffrey Lebowski they are after. Before leaving, however, the second thug urinates on the Dude’s rug. It is a rug the Dude valued very highly, as in his estimation it "really tied the room together."

The Dude’s peaceful lifestyle is suddenly compromised at the beginning of the film. Two thugs turn up at his apartment demanding money that they claim his wife has stolen from a man named Jackie Treehorn; one of them even jams the Dude’s head in the toilet to underscore their seriousness. When the Dude finally protests that he doesn’t have a wife ("the toilet seat is up, man!"), the thugs look scornfully around the ramshackle flat and realize that this must not be the Jeffrey Lebowski they are after. Before leaving, however, the second thug urinates on the Dude’s rug. It is a rug the Dude valued very highly, as in his estimation it "really tied the room together."

The next day, after sharing the indignity with his bowling partners, Walter, a bombastic Vietnam War veteran played by John Goodman convinces the Dude to locate the other Jeffrey Lebowski the thugs were looking for, in order that he provide compensation for the damaged rug. The subsequent uncharacteristic level of initiative on the Dude’s part sets off a bizarre chain of events in which he awkwardly adopts a role as private investigator for the other ("Big") Lebowski, a cantankerous, condescending tycoon whose debt-ridden trophy wife has just been kidnapped.

In what follows, this stoned old hippie finds himself placed in a role straight out of a typical noir film from the mid-20th century. In fact, the very title of The Big Lebowski is taken from 1946’s The Big Sleep and pays homage to many of that film’s signature elements. But of course, the Dude is no Humphrey Bogart, and much of the film’s more obvious hilarity ensues from this odd, highbrow twist on the "fish-out-of water" scenario featured in many popular modern films.

In what follows, this stoned old hippie finds himself placed in a role straight out of a typical noir film from the mid-20th century. In fact, the very title of The Big Lebowski is taken from 1946’s The Big Sleep and pays homage to many of that film’s signature elements. But of course, the Dude is no Humphrey Bogart, and much of the film’s more obvious hilarity ensues from this odd, highbrow twist on the "fish-out-of water" scenario featured in many popular modern films.

As one would expect, figuring out the caper proves to be quite a wild ride for the normally indolent Dude — and for the audience as well. But by the end of the film, after repeatedly overturning the audiences expectations with myriad red herrings and dead ends, many viewers find themselves unsure what they just witnessed. Bizarre characters have waltzed on and off the screen, only to reappear in various guises — occasionally in dream sequences brought on by the Dude getting knocked out or drugged. As with many a film noir, it’s unsure who exactly is on the level and it is only at the end that the Dude, by dint of pure luck and a bit of "limber" thinking (courtesy of pot and alcohol), is able to figure everything out.

For some viewers, the film’s resolution is terribly unsatisfying — almost pasted-on. Yet for others, especially those who’ve bothered to see it a second or third time, it very cleverly ties the whole film together. Nevertheless, for serious aficionados, its neo-noir plot as well as its unexpected ending hardly figure into its appeal. Rather, it’s the mass of brilliant dialogue, clever cinematography, subtle symbolism, disarming pathos and unique philosophy embedded throughout the film that helps distinguish it as a true original in the history of cinema.

For some viewers, the film’s resolution is terribly unsatisfying — almost pasted-on. Yet for others, especially those who’ve bothered to see it a second or third time, it very cleverly ties the whole film together. Nevertheless, for serious aficionados, its neo-noir plot as well as its unexpected ending hardly figure into its appeal. Rather, it’s the mass of brilliant dialogue, clever cinematography, subtle symbolism, disarming pathos and unique philosophy embedded throughout the film that helps distinguish it as a true original in the history of cinema.

Certainly the film has its antecedents — that is, works which have attempted to imbue comedy with the type of depth of meaning and wealth of poetry normally found in great drama. Novels like Tristram Shandy and A Confederacy of Dunces and films like Withnail and I and Pulp Fiction have all done this to a degree. Yet arguably, not since Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (written 400 years earlier) has a story so hilarious turned out to be so deceivingly multi-layered, so unexpectedly profound as The Big Lebowski.

The Cult of Lebowski

"At least it’s an ethos."

Of course, whether "The Dude" endures quite as long as "The Don" remains to be seen. For now, at least, the film is rapidly becoming an colorful part of many college curricula. In fact, a book of scholarly dissertations of the film will shortly be published by the University of Louisville Press [note: it’s already been published]. Several other books concerning The Big Lebowski have been published or will be published within the next year, helping ensure its legacy lives on.

Among those books are:

- I’m a Lebowski, You’re a Lebowski by Bill Green, Ben Peskoe, Scott Shuffitt & Will Russell

- BFI Film Classics: The Big Lebowski by J.M. Tyree & Ben Walters

- The Dude Abides by Cathleen Falsani

- The Making of The Big Lebowski by William Preston Robertson & Tricia Cooke

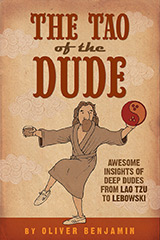

- The Tao of the Dude by Oliver Benjamin

- The Year’s Work in Lebowski Studies by Edward Comentale and Aaron Jaffee

- The Abide Guide by Oliver Benjamin and Dwayne Eutsey

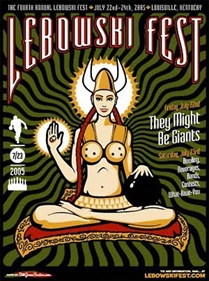

It’s not just books that are helping to keep the film alive in the public awareness. Most famously, a traveling festival called Lebowskifest regularly attracts thousands of Lebowski fans several times a year to various sites in the US and the UK, and is now in its 8th year of operation. Several actors from the movie, including Jeff Bridges have attended, as well as Jeff Dowd, the real-life inspiration for the Dude character. One of the books listed above, I’m a Lebowski, You’re a Lebowski was compiled by the festival’s organizers and continues to be a best-seller in its category over a year after its first printing.

Furthermore, there’s an actual religion devoted to the teachings of the Dude — Dudeism. "The Church of the Latter Day Dude," as it is officially known is inspired by the Dude’s example and the philosophies evinced in the movie. Currently the church has over 50,000 freely-ordained "Dudeist Priests," and an average of a hundred new ones sign up every day. Besides the Dude, the creed draws inspiration from other Dudeish characters and real-life Dudeist prophets throughout history, such as Lao Tzu, Epicurus, Snoopy, George Carlin and many more. In 2008, The Church of the Latter-Day Dude began publishing The Dudespaper, a "Lifestyle Magazine for the Deeply Casual" which aims to promote the ideals of Dudeism.

There is also a regular podcast which addresses aspects of the film and helps promote Lebowskian culture via their downloadable discussions.

Initial Critical Response

"You’re out of your element!"

By the mid 1990s, the Coen Brothers stood alongside other intellectual-but-fun filmmakers such as Woody Allen and Jim Jarmusch in earning critical acclaim while earning little at the box office. Bloated effects budgets and star salaries had conspired to make independent "art house" films increasingly embattled at this time and it was only through lean production and the enthusiasm of sympathetic A- and B-list actors that they were able to continue to churn out exceptional dark and offbeat dramas and comedies. Though they were often celebrated overseas (they won Cannes highest award, the Palme d’Or for Barton Fink), the Coens and their films remained relatively unrecognized in their home country.

That all changed in 1996 when their unexpected sleeper hit Fargo won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (Joel’s wife Frances McDormand, a regular in their films, also won in the Best Actress category). Suddenly the Coens found themselves media darlings, treated with the attention they’d been denied for decades prior. It was a mystery to the brothers why Fargo was the one that clicked with audiences and critics, especially considering it was bleaker in tone than their prior efforts. Despite their newfound success, the brothers remained as laconic and reticent as they had always been, confounding interviewers with their typical deadpan answers to probing questions, if not outright silence.

That all changed in 1996 when their unexpected sleeper hit Fargo won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (Joel’s wife Frances McDormand, a regular in their films, also won in the Best Actress category). Suddenly the Coens found themselves media darlings, treated with the attention they’d been denied for decades prior. It was a mystery to the brothers why Fargo was the one that clicked with audiences and critics, especially considering it was bleaker in tone than their prior efforts. Despite their newfound success, the brothers remained as laconic and reticent as they had always been, confounding interviewers with their typical deadpan answers to probing questions, if not outright silence.

Expectations ran high for the release of their next film, The Big Lebowski. But when it came out, critical response was mixed at best. The wacky comedy seemed almost a slap in the face for fans of Fargo — as opposed to that film’s haunting, cynical mediation on human greed and dissatisfaction, here was a goofy, lighthearted yarn that seemed to make no sense at all and have absolutely nothing meaningful to say about anything. Most critics gave it a similar reception to their other higher-budgeted, star-studded film The Hudsucker Proxy, which had been labeled "a pastiche too far."

The brothers quickly bounced back after Lebowski with hits like O Brother Where Art Thou and Intolerable Cruelty, not to mention winning multiple Oscars in 2007 with No Country for Old Men. But all the while, gradually, as if behind the scenes, Lebowski had been steadily building steam, buoyed by a grassroots coalition of fans, fomented most notably by those involved with Lebowskifest. This, together with strong business in the DVD and rental markets and a high level of repeat viewing drew notice of the press, who have increasingly acknowledged the growing cult-like appreciation of the film.

The brothers quickly bounced back after Lebowski with hits like O Brother Where Art Thou and Intolerable Cruelty, not to mention winning multiple Oscars in 2007 with No Country for Old Men. But all the while, gradually, as if behind the scenes, Lebowski had been steadily building steam, buoyed by a grassroots coalition of fans, fomented most notably by those involved with Lebowskifest. This, together with strong business in the DVD and rental markets and a high level of repeat viewing drew notice of the press, who have increasingly acknowledged the growing cult-like appreciation of the film.

Current Criticism

"A lotta ins, a lotta outs, a lotta what-have-yous."

As criticism and interpretation of The Big Lebowski gathers momentum, new ideas about the film are popping up all the time. What follows are just a few of the impressions critics have come up with over the last decade.

The Decline of the American Male

Lebowskitheory.com presents a cohesive and compelling thesis that the movie portrays the emasculated position the average American male at this moment in history. With women occupying increasingly powerful positions in society, and consequently not requiring the traditional male role of provider to take care of them, men have lost much of their societal cache and control. The Dude and his cohorts Walter and Donnie represent "losers" in this system — where they have neither status, money, nor females and can only count on each other for companionship and mutual respect. Presented in comedic form with a devil-may-care attitude, the film provides comfort to some male viewers, assuring them they’re not alone, and that perhaps this loss of inherited cultural identity is not such a big deal after all.

The Modern Hero

The narrator’s rumination on the Dude as something akin to a hero, "I won’t say a hee-ro exactly, because what’s a hee-ro?" sets the stage for the film’s repeated examinations on "what makes a man." The traditional idea of the crusading man-of-action gets short shrift in the film, most tellingly as a somewhat outdated idea that may no longer be relevant today. The film introduces several farcical versions of traditional heroes: the cowboy, the private investigator, the war hero, the tycoon, the sports hero, the libertine, the trickster, even The Jesus — an utterly perverted, dissolute version of his heroic biblical namesake. The only clear non-hero among then (besides Donnie) is the Dude, who — though technically the protagonist of the film — champions few if any of the qualities or goals of the traditional fictional hero. As he puts it himself, "all the Dude wanted was his rug back." It’s hardly an epic crusade. This feeble impetus gleefully flies in the face of most modern cinema, which demands that the main character have a clear goal — any goal, what Alfred Hitchcock abstractly termed "The MacGuffin."

The Genre Mash-Up

Given that it features such a broad range of heroic stereotypes, it’s only natural that elements of their respective genres feature in the film. Played against one another, the result can be both comical and illuminating. Most obviously, it reveals the real-world shortcomings of those stereotypes. In placing the hapless Dude in the always-capable role of noir private investigator several assumptions about macho steadfastness are re-evaluted: Namely, sometimes what seems to need fixing is better left alone. Similarly, Walter’s over-the-top military response to minor transgressions are shown to be utterly pointless and ineffective, in fact generally making every situation worse than it needs to be. And the Busby Berkeley dance number that plays out in the Dude’s head after being drugged by Jackie Treehorn makes a farce out of old-fashioned cinematic romance, while the mechanical, emotionless coupling of Maude with the Dude proves antithetical to the common tropes of modern romantic comedy. Finally, unlike most buddy comedies featuring a pair of opposites, the Dude and Walter ultimately learn absolutely nothing from each other, remaining friends out of habit and convenience, and because they’ve got nowhere else to go.

The Eastern Western

In contrast with the film’s numerous Western heroic stereotypes, the character of the Dude is recognized by many critics to taken directly from the Eastern mold. The Dude’s lifestyle and attitude neatly mirror that of several Asian sages, particularly Lao Tzu, the founder of Taoism. Taoism’s basic outlook is that aggression only begets more aggression, and that one lives in harmony with the world only when they "go with the flow" and not try to achieve too much. Additionally, many see elements of Zen Buddhism in the film. For instance, Jeff Bridges’ friend and Zen teacher Bernie Glassman offered Zen Dudeist widsom on his website (removed sometime in 2009). Inadvertently espousing the virtues of Buddhism, the Dude keeps his mind free from attachments and the idea that truth is hard and palpable. Most importantly, he diligently treads the "middle path," that is to say, he practices moderation in all things. It is only when steered from his accustomed course by his friend Walter (whom Buddhists might associate with their mythological tempter demon Mara) that he loses his footing and his life falls into shambles. When all is said and done, though he finds his "center" once more, offering the meditative-sounding mantra, the line viewers tend to associate most with the film: "The Dude Abides."

Characters and Cast

"Oh, I know that guy"

[Note: Character descriptions may contain some spoilers. If you haven’t seen the film yet, you might want to do so first]

Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges)

Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges)

An unemployed, unmarried, underachiever in his 40s who appears perfectly happy to spend his days hanging out with friends, bowling, and getting high on marijuana, White Russians, and beer. He has no interest in getting married or having kids, nor pursuing anything resembling an actual career. His temperament is generally extremely easygoing, and he only succumbs to flashes of anger when manipulated by others for their own ends. While the Dude achieved some renown in his youth as a member of the Seattle Seven and as an original author of the Port Huron Statement, he has done little worth noting in his life since, other than a brief stint as a roadie for the heavy metal band Metallica. Early versions of the script explained his unemployment on the fact that he was heir to the Rubik’s cube fortune, but the Coens later removed this from the screenplay. The character is in fact based on a real person — a friend of the Coens named Jeff Dowd, a movie producer and promoter who also referred to himself as "The Dude." Dowd was an actual member of the Seattle Seven but had nothing to do with the Port Huron Statement.

A veteran of the Vietnam War, Walter is obsessed with what he and his fellow soldiers were forced to endure during their duty. Consequently Walter sees parallels to Vietnam in every struggle he — or anyone else — is forced to contend with, no matter how mundane. Though critically aware of the horrors of war, Walter is fiercely militant, believing that war is a necessary part of life and crucial to maintain order in a world infested with both corrupt elites and lowlife criminals. Though prone to break into violent fury, he’s also deeply loyal and even affectionate to those close to him. He’s also revealed to be a bit of a romantic softie, particularly insofar as he can not let go of his attachment to his ex-wife Cynthia. For example, though he converted to Judaism when they married, now that they’re divorced he is vociferously adamant about clinging to the tenets of that faith, most probably for nostalgic reasons. His character was based primarily on film writer/director John Milius.

Theodore Donald "Donnie" Kerabatsos (Steve Buscemi)

Theodore Donald "Donnie" Kerabatsos (Steve Buscemi)

The third member of the Dude’s primary circle of friends. Though a good bowler, he comes off as a little demented. Donnie never seems to understand what is going on in any given situation, and is discouraged from ever finding out by Walter who continually screams at him to "Shut the f**k up, Donnie!" We find out later that he was a surfer as well as a bowler, which could be an allusion to the fact that the old cowboy term "dude" was brought back to popularity by surfers in California in the 1970s. The reason Donnie is never allowed to speak is because Buscemi’s character in the Coens’ previous film Fargo would never shut up.

Jeffrey ("The Big Lebowski") Lebowski

Jeffrey ("The Big Lebowski") Lebowski

(David Huddleston)

A paraplegic tycoon who lives in a mansion in Pasadena, he claims to be a self-made man who "went out and achieved anyway, even without the use of his legs." After the Dude visits him to demand recompense for his soiled rug, The Big Lebowski refuses to accede, insulting his evident lack of employment and ambition in life. Nevertheless, days later the Big Lebowski calls The Dude back to act as courier and investigator to bring ransom money to a group that has kidnapped Bunny, his young trophy wife. Due to the commission involved, as well as the old man’s apparent distress and sorrow, Dude agrees to help. However, later in the film when the Dude appears to be screwing up the job ("They didn’t receive the money you nitwit!"), Lebowski grows angrier and angrier, threatening the Dude with violence. Ultimately, we find that for all his bluster and bravado, The Big Lebowski is a fraud. His character is partially modeled on the character of General Sternwood from The Big Sleep.

Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore)

Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore)

The daughter of The Big Lebowski, Maude is an artist whose paintings have been commended as "strongly vaginal." She contends that her father has taken the ransom money from a charity he runs, "The Little Lebowski Urban Acheivers" and, keen to set things right, hires the Dude to recover the money, raising the Dude’s commission over what her father promised him. Proudly feminist, Maude nevertheless insists that contrary to the stereotype of many feminists, she is fond of sex, which she calls a "natural, zesty enterprise." Ultimately, she pursues The Dude for a one-off dalliance. Though the Dude imagines it’s purely for recreational purposes, she is actually looking to become inseminated, though as it turns out she has no interest in having him help raise the child.

The third character to enlist the Dude’s services as private investigator, Treehorn is a porn movie producer who had worked with Bunny Lebowski (called "Bunny LaJoya" in her films). Bunny has apparently disappeared and reneged on a sizable debt to Treehorn, and Treehorn believes Dude knows where the money is. After providing a ludicrous answer (which The Dude nevertheless believes to be true), Treehorn drugs him and ransacks his apartment in search of the money. Treehorn is also responsible for the thugs visiting the Dude at the beginning of the film — evidently he originally suspected that the other Jeffrey Lebowski had his hands on the missing cash.

Uli ("Karl Hungus") Kunkel (Peter Stormare)

Uli ("Karl Hungus") Kunkel (Peter Stormare)

A German-born self-described Nihilist, and the presumed kidnapper of Bunny, together with his two fellow German Nihilists Franz and Dieter. Formerly the leader of an 80s technopop band called "Autobahn" (together with the other two), he knows Bunny from working with her on porn films in which his screen name was "Karl Hungus." Since the Nihilists are the ones demanding the ransom money, we are led to believe that they are in fact her kidnappers. In the end they stage a showdown with The Dude, Donnie and Walter, but Walter beats them all single-handedly. Though cocky and brash about their Nihilism, they in fact turn out to be "cry babies" (Walter’s words) in search of some easy cash.

Bunny Lebowski (Tara Reid)

Bunny Lebowski (Tara Reid)

The beautiful but tawdry twenty-something trophy wife of The Big Lebowski, Bunny has obviously married him for his money and ostensibly to get out of her previous career as a porn actress. Evidently, she appears to be unsatisfied with the allowance he provides her, as she immediately offers The Dude oral sex for a thousand dollars at their first meeting. Near the end of the film she’s revealed to be a Minnesotan runaway originally named Fawn Knudsen, and who’s parents have hired a professional private investigator to track down and bring home to the family farm.

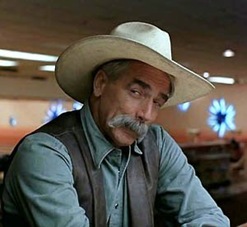

The Stranger (Sam Eliott)

The Stranger (Sam Eliott)

The narrator of the film, The Stranger is explicitly named so only in the screenplay. He speaks in an antiquated Wild West dialect and dresses as if he’s come straight out of that era as well. We know little about him other than that he’s impressed with the Dude’s attitude and sees him as "the man for his time and place." His character most likely provides a framing device for the story — placing it in the context of the great American frontier and its westward expansion, as well as offering a statement on the current state of the American hero.

Brandt (Phillip Seymour Hoffman)

Brandt (Phillip Seymour Hoffman)

Assistant to The Big Lebowski, Brandt is a spineless sycophant in the tradition of "Smithers" on the TV series The Simpsons. Exuding so much awkward, ingratiating affect, it’s hard to know what Brandt actually knows and doesn’t know — he has virtually no personality of his own, except for a constant, bumbling nervousness that seeps through his manicured facade.

Jesus "The Jesus" Quintana (John Turturro)

Jesus "The Jesus" Quintana (John Turturro)

The arch-bowling nemesis of The Dude, Walter and Donnie. The Jesus is a Hispanic bowling aficionado with unusual character traits and sartorial tastes. Revealed by Walter to have been jailed for pederasty (he exposed himself to an 8-year old), The Jesus is sexually vulgar and a highly confrontational opponent. Though he occupies only a few minutes of screen time and serves no purpose in the film other than a bit of comic relief, he continues to be one if its most popular characters. John Turturro has revealed in interviews that the Coen brothers might agree to doing a Big Lebowski spin off one day in which The Jesus is the main character.

Da Fino (Jon Polito)

Da Fino (Jon Polito)

A private investigator whom the Dude notices is following him at various times throughout the film. When the Dude finally confronts him he finds out that Da Fino was hired by the Knudsens — Bunny Lebowski’s parents — to find her and bring her back home. Da Fino expresses his admiration for The Dude’s sleuthing, presuming he has been intentionally playing one side against the other, and suggests they team up. He refers to himself colorfully as a "brother shamus," a "private snoop" and a "dick" — old-fashioned slang terms for those in his profession.

Martin "Marty" Randall (Jack Kehler)

Martin "Marty" Randall (Jack Kehler)

The Dude’s Landlord, and an amateur interpretive dancer. He’s easygoing about collecting rent and appears more concerned that The Dude attends the performance of his dance "cycle." Midway through the film, The Dude, Walter and Donnie show up for the performance but none appear very impressed. In it, Marty dresses up as an ivy-draped cherub and dances with awkward abandon to "Pictures at an Exhibition."

One of the opponents of Dude, Walter and Donnie. During one of their league games, Walter believes that Smokey’s toe has slipped over the foul line and demands that he receive no points. Smokey disagrees and tells The Dude to mark the score eight. This impels Walter to pull out a gun and threaten to shoot Smokey if he doesn’t comply with "the rules." As they flee the bowling alley in advance of the police, The Dude admonishes Walter for being so hard on Smokey, who he maintains is sensitive and a pacifist. The actor who plays Smokey, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, is a real-life country musician (and a pacifist).

Interesting Trivia

"I did not know that."

- The F-word and its variants are uttered 281 times, putting it in the top 20 films of all time as measured by how many times the word is spoken.

- "Man" is said 147 times.

- "Dude" and its variations are said 161 times.

- At the beginning of the film The Dude writes a check for a half gallon of half-and-half to mix White Russians with. The amount on the check is only 69 cents. Eerily, he dates it September 11, 1991, exactly ten years before the bombing of the World Trade Center, and he’s watching George Bush Sr. on the supermarket’s television declaring war on Iraq as he does so.

- The movie contains several allusions to existentialism. The narrator’s name "The Stranger" is the same as the title of a seminal existentialist book by Albert Camus. A copy of Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness is on The Dude’s bedside table. Moreover, nihilism and existentialism have so much in common that they are often confused.

- Many of the Dude’s clothes actually came from Jeff Bridges’ private collection. The jelly sandals were his too.

- In the greatroom scene where The Big Lebowski tells him of Bunny’s kidnapping, The Dude wears a baseball shirt with a drawing of a Japanese baseball star. Jeff Bridges wore the same shirt in an earlier film, The Fisher King.

- The animals mentioned in the movie are identified incorrectly. Walter’s ex-wife’s dog is not a Pomeranian but a terrier. The "marmot" thrown into the Dude’s bathtub by the Nihilists is actually a ferret.

- The screenplay calls for Dude’s car to be a Chrysler LeBaron, but it turned out to be too small for the plus-sized John Goodman to move around in it properly. It was replaced with a larger Ford Gran Torino.

- There were two Gran Torinos used in the film. One was destroyed in the film and the other was destroyed in an X-Files episode.

- Before filming a scene, Bridges would ask the Coens if The Dude was meant to be high at the time. If he was, he rubbed his knuckles into his eyes to make them appear bloodshot.

- Metallica’s "Speed of Sound" tour that the Dude said he roadied for never took place. They never came out with an album of that name.

- The Blue Volkswagen driven by Da Fino is an homage to the car driven by the villain in the Coens’ first film, Blood Simple.

Links

"Have you got any leads?"

- The Movie:

- Books:

- I’m a Lebowski, You’re a Lebowski by Bill Green, Ben Peskoe, Scott Shuffitt & Will Russell

- BFI Film Classics: The Big Lebowski by J.M. Tyree & Ben Walters

- The Dude Abides by Cathleen Falsani

- The Making of The Big Lebowski by William Preston Robertson & Tricia Cooke

- The Tao of the Dude by Oliver Benjamin [this article’s author]

- Lebowskifest

- Dudeism

- The Dudespaper

- Lebowskipodcast.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.