By David Masciotra

By David Masciotra

Dudeists looking to The Dude for instruction and inspiration should seek to find, identify, and befriend a miniature and personDude in their own lives. The following is an excerpt from my book in progress called Faith That Won’t Die: Death, Defeat, Sex, and Spirituality in One Rust Belt Town. In this passage I describe my own personal Dude—an English professor at the University of St. Francis, which is a small, Catholic liberal arts college in Joliet, IL.

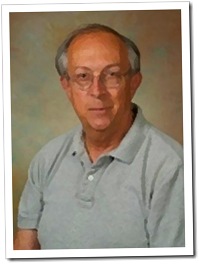

The first person I met with at the University of St. Francis—my alma mater—on my first day of work as an adjunct English instructor was English professor Marvin Katilius-Boydstun, “Vin.” I was Vin’s student before working for him as a writing tutor and teaching assistant.

Author and priest Addison Hart brilliantly distinguishes spiritual friendship from superficial friendship. Superficial friendship turns on socializing, while spiritual friendship “is a uniting of minds and hearts at a deep level.” The unity of friendship is maintained in “in relationship to those we have grown to love and trust, whose support upholds us.”

Vin is a spiritual friend and a spiritual brother. For hours we would sit in his office when I was an earnest atheist and argue about the validity of God and the value of religion. His deceptively soft and Socratic style of argumentation didn’t convert or convince me at the time, but years later when I was in the middle of a spiritual awakening, my mind wouldn’t stop hitting the rewind button and replaying his questions and insights, which were so tightly packed with wisdom it took years of pulling, prying, and plunging to get to the center. The hands of my intellect were bleeding to the bone, but my spirit gained a new set of skin.

Vin is a spiritual friend and a spiritual brother. For hours we would sit in his office when I was an earnest atheist and argue about the validity of God and the value of religion. His deceptively soft and Socratic style of argumentation didn’t convert or convince me at the time, but years later when I was in the middle of a spiritual awakening, my mind wouldn’t stop hitting the rewind button and replaying his questions and insights, which were so tightly packed with wisdom it took years of pulling, prying, and plunging to get to the center. The hands of my intellect were bleeding to the bone, but my spirit gained a new set of skin.

Vin barely noticed my quiet entrance through the open doorway of his office, and only stood up once I announced myself with a “hey Vin.” Dressed in his standard uniform—flannel shirt, faded jeans, and brown loafers—he stood with his hand out waiting for me to shake. As quickly as he stood up, he sat back down returning to his  equally standard pose—crossed feet resting on his desk, clenched hands on the back of his balding head. He handed me six folders, each with a student’s name written on it, and provided some guidance for leading the weekly scheduled tutorials I have with these students who have enrolled in the supplemental course with me because they have difficulty writing at a college level. His instruction didn’t last long—it didn’t need to—and quickly turned over into a discussion of Jack Nicholson film noir classics—Postman Always Rings Twice, Ironweed, and the criminally underrated Blood and Wine. The specifics of our discussion, which ranged from film criticism to literary theory to amateur philosophy, aren’t very important, but they capture the intellectual experience of campus life at its best. Rarely do the most memorable mind-altering moments take place in the classroom. More often they happen in the student lounges, faculty offices, and late night barroom discussions—all of which lead you to realize that, as Cornel West says, “Your worldview rests on a foundation of pudding.”

equally standard pose—crossed feet resting on his desk, clenched hands on the back of his balding head. He handed me six folders, each with a student’s name written on it, and provided some guidance for leading the weekly scheduled tutorials I have with these students who have enrolled in the supplemental course with me because they have difficulty writing at a college level. His instruction didn’t last long—it didn’t need to—and quickly turned over into a discussion of Jack Nicholson film noir classics—Postman Always Rings Twice, Ironweed, and the criminally underrated Blood and Wine. The specifics of our discussion, which ranged from film criticism to literary theory to amateur philosophy, aren’t very important, but they capture the intellectual experience of campus life at its best. Rarely do the most memorable mind-altering moments take place in the classroom. More often they happen in the student lounges, faculty offices, and late night barroom discussions—all of which lead you to realize that, as Cornel West says, “Your worldview rests on a foundation of pudding.”

Vin’s belief in the value of higher education and the promise of the University of St. Francis steadily weakened as he watched tuitions rates skyrocket, liberals arts diminish, and the hiring of part time instructors when there are thousands of out-of-work intellectuals grow ever more common and contemptible. Unfortunately, none of these shameful developments are unique to USF or any other school. They are all part of a larger movement in American education that places profit over people and pecuniary gain over principled commitment. As college administrators and board members turn to cost and throat cutting business measures to run their schools, faculty becomes detached from the world outside their well-protected walls. Vin went so far as saying that, with few exceptions, there is “no attachment” to the poor, working class, or anyone else that could directly benefit from the assistance, instruction, and outreach of the educational elite. He told me a story that perfectly captured the changes and behavioral model that causes him to worry about the future of higher education in America.

Vin’s belief in the value of higher education and the promise of the University of St. Francis steadily weakened as he watched tuitions rates skyrocket, liberals arts diminish, and the hiring of part time instructors when there are thousands of out-of-work intellectuals grow ever more common and contemptible. Unfortunately, none of these shameful developments are unique to USF or any other school. They are all part of a larger movement in American education that places profit over people and pecuniary gain over principled commitment. As college administrators and board members turn to cost and throat cutting business measures to run their schools, faculty becomes detached from the world outside their well-protected walls. Vin went so far as saying that, with few exceptions, there is “no attachment” to the poor, working class, or anyone else that could directly benefit from the assistance, instruction, and outreach of the educational elite. He told me a story that perfectly captured the changes and behavioral model that causes him to worry about the future of higher education in America.

“One day I was walking from my office to the cafeteria, and I passed the student lounge near the main entrance of Tower (Tower Hall). One of the Art Professors and some of his students were shaving people’s heads in the middle of the lounge, and a large crowd was watching. I just thought, ‘oh God, performance art,’ and kept walking. Didn’t think much of it. I ate lunch and started walking back to my office. When I walked past the same lounge, the crowd was gone, nobody was around, except one person: A maintenance worker—a cleaning woman sweeping up all the hair. No one bothered to watch that.”

“One day I was walking from my office to the cafeteria, and I passed the student lounge near the main entrance of Tower (Tower Hall). One of the Art Professors and some of his students were shaving people’s heads in the middle of the lounge, and a large crowd was watching. I just thought, ‘oh God, performance art,’ and kept walking. Didn’t think much of it. I ate lunch and started walking back to my office. When I walked past the same lounge, the crowd was gone, nobody was around, except one person: A maintenance worker—a cleaning woman sweeping up all the hair. No one bothered to watch that.”

Vin went on to comment how too many people within academia are too busy playing smart games designed only to showcase their education, intellect, and creativity to give attention to the plight and predicament of everyday people. While the administrators and board members undermine the purpose and meaning of a liberal arts education, the faculty distract themselves with the pursuit of socially disconnected and hollowly clever personal projects. It should go without saying that at every campus there are faculty members who loudly object to the status quo, and rather than busying themselves with distractions, fully engage in important struggles. The University of St. Francis has many faculty members like this—perhaps even more than most. But, even there, one cannot help but notice the creeping moral indifference that resembles the growing selfishness of American culture.

Rebellion comes in many forms, and in an era of hegemonic greed, omnipresent corruption, and reckless narcissism, it is difficult to determine which kind is more effective—outspoken protest or quiet resistance. Vin’s choice is the latter. He lives in the tradition of Melville’s Bartleby who reacted to the inequality and injustice of the world with total withdrawal, saying “I would prefer not to” whenever anyone—his employer, local authorities, anyone—asked him to do anything ranging from the simplest tasks to the duties of his job. Slavoj Zizek posits that what he calls “Bartleby politics” may be the sanest response to the dictums of a broken and rotted social order. It is not cynicism or obliviousness, but a personal internalization of the inconsistency and injustice of the system in which we inhabit, and an attempt to suspend—even if only for a fleeting moment—the vicious cycle of that self-serving system. “Bartleby politics” is the inspiration, intentional or not, for one of the greatest characters in all of American cinema—The Dude. Jeff Bridges plays Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski in the Coen Brothers masterpiece, The Big Lebowski.

Rebellion comes in many forms, and in an era of hegemonic greed, omnipresent corruption, and reckless narcissism, it is difficult to determine which kind is more effective—outspoken protest or quiet resistance. Vin’s choice is the latter. He lives in the tradition of Melville’s Bartleby who reacted to the inequality and injustice of the world with total withdrawal, saying “I would prefer not to” whenever anyone—his employer, local authorities, anyone—asked him to do anything ranging from the simplest tasks to the duties of his job. Slavoj Zizek posits that what he calls “Bartleby politics” may be the sanest response to the dictums of a broken and rotted social order. It is not cynicism or obliviousness, but a personal internalization of the inconsistency and injustice of the system in which we inhabit, and an attempt to suspend—even if only for a fleeting moment—the vicious cycle of that self-serving system. “Bartleby politics” is the inspiration, intentional or not, for one of the greatest characters in all of American cinema—The Dude. Jeff Bridges plays Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski in the Coen Brothers masterpiece, The Big Lebowski.

The Dude is a happily unemployed, grass smoking, White Russian drinking, hippie bowler living in Los Angeles. He was one of the authors of the “original Port Huron statement” and a former roadie for Metallica, who he claims are a “bunch of assholes.” “The Dude abides” and “take it easy” are his two mottos, which summarize his life philosophy—resistance and withdrawal. His commitment to loafing and quietly exiting from capitalist America is tested when two men break into his apartment and piss on his rug because they believe he is the millionaire Jeffrey Lebowski, whose wife owes money “”all over town, including to the known pornographers.” The film is rewatchable over and over again because it never ceases to be funny, the characters grow increasingly lovable, and because it is the most entertaining examination of the conflict of competing values and clash of cultures that define America and test the validity and limits of Bartleby politics. “All the Dude ever wanted was his rub back,” he says, but the attempt to find a replacement rug takes him on a noir-like investigation into the background of Lebowski—one of the richest and most powerful men of California—the business dealings of Jackie Treehorn—a wealthy political lobbyist who is also a pornographer—and a bizarre band of nihilist gangsters who are wrapped up with Lebowski and Treehorn. In the beginning of the movie, Lebowski screams “the bums will always lose” to The Dude, and by the end of the movie The Dude, with help from his Vietnam veteran friend Walter Sopchek played by John Goodman, reveals that Lebowski is actually the bum. He is broke, barely living off an allowance from his rich, feminist painter daughter, and siphoning money from a fund for underprivileged children the daughter established in his name. Ironically, The Dude makes earth-shattering discoveries by doing as little as possible, thereby demonstrating the subversive nature of Bartleby politics. Only someone with as little connection and little interest in the system of greed, status, and power as The Dude, could so utterly destroy it.

The Dude is a happily unemployed, grass smoking, White Russian drinking, hippie bowler living in Los Angeles. He was one of the authors of the “original Port Huron statement” and a former roadie for Metallica, who he claims are a “bunch of assholes.” “The Dude abides” and “take it easy” are his two mottos, which summarize his life philosophy—resistance and withdrawal. His commitment to loafing and quietly exiting from capitalist America is tested when two men break into his apartment and piss on his rug because they believe he is the millionaire Jeffrey Lebowski, whose wife owes money “”all over town, including to the known pornographers.” The film is rewatchable over and over again because it never ceases to be funny, the characters grow increasingly lovable, and because it is the most entertaining examination of the conflict of competing values and clash of cultures that define America and test the validity and limits of Bartleby politics. “All the Dude ever wanted was his rub back,” he says, but the attempt to find a replacement rug takes him on a noir-like investigation into the background of Lebowski—one of the richest and most powerful men of California—the business dealings of Jackie Treehorn—a wealthy political lobbyist who is also a pornographer—and a bizarre band of nihilist gangsters who are wrapped up with Lebowski and Treehorn. In the beginning of the movie, Lebowski screams “the bums will always lose” to The Dude, and by the end of the movie The Dude, with help from his Vietnam veteran friend Walter Sopchek played by John Goodman, reveals that Lebowski is actually the bum. He is broke, barely living off an allowance from his rich, feminist painter daughter, and siphoning money from a fund for underprivileged children the daughter established in his name. Ironically, The Dude makes earth-shattering discoveries by doing as little as possible, thereby demonstrating the subversive nature of Bartleby politics. Only someone with as little connection and little interest in the system of greed, status, and power as The Dude, could so utterly destroy it.

If Vin were not employed as a full time English professor, he would be Joliet’s version of The Dude. He is admittedly lazy, he never applied for tenure because he objects to the tenure system and he didn’t feel like going through the process in which he must impress bureaucrats and administrators with sufficient conformity to their codes, by-laws, and policies, he routinely ignores instructions from the deans, and has isolated himself from the endless committee meetings and internal debates of USF. Because he never applied for tenure, he has to apply for contract renewals every three years, and has risked denial by not complying with arbitrary demands for documentation of credentials and recommendations. He sees the system in perpetual decline, falling further away from the ideals he committed to many years ago, and therefore he falls further away from the system, content to use his literature courses and office hours as means of quiet protest that give thoughtfully alternative philosophy lessons to his students. He recommends philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s pamphlet On Bullshit to everyone who darkens his door, and has been on the receiving end of scorn from many colleagues for responding to their self-congratulatory rhetoric, such as an Education professor’s proposal for instilling “moral values” in elementary students as part of curriculum for education majors, by simply calling it “bullshit.”

If Vin were not employed as a full time English professor, he would be Joliet’s version of The Dude. He is admittedly lazy, he never applied for tenure because he objects to the tenure system and he didn’t feel like going through the process in which he must impress bureaucrats and administrators with sufficient conformity to their codes, by-laws, and policies, he routinely ignores instructions from the deans, and has isolated himself from the endless committee meetings and internal debates of USF. Because he never applied for tenure, he has to apply for contract renewals every three years, and has risked denial by not complying with arbitrary demands for documentation of credentials and recommendations. He sees the system in perpetual decline, falling further away from the ideals he committed to many years ago, and therefore he falls further away from the system, content to use his literature courses and office hours as means of quiet protest that give thoughtfully alternative philosophy lessons to his students. He recommends philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s pamphlet On Bullshit to everyone who darkens his door, and has been on the receiving end of scorn from many colleagues for responding to their self-congratulatory rhetoric, such as an Education professor’s proposal for instilling “moral values” in elementary students as part of curriculum for education majors, by simply calling it “bullshit.”

He is the Dude of USF and like The Dude, he may be only one insult, infraction, or injustice away from activating his Bartleby politics. Just as the Dude needed someone to piss on his favorite rug, Vin may need only a contemptuous move against him—some unforeseen provocation—to take on a fully Dude-like presence of the fly in the ointment. He would strike a small, but scarring blow against the corporate model of the modern university, and perhaps, win a fight for the Catholic liberal arts tradition.

Richard Russo writes about a Vin-like character in his novel Straight Man. The protagonist is William Henry Devereaux Jr., the reluctant chairman of the English department of a badly underfunded college in Pennsylvania rust belt. Devereaux, like Vin, is quiet, stays out of people’s way, and does his best to remove himself from the boring and small-minded affairs of academic committees and in-fighting. He also doesn’t take any shit, and like Vin rebels against the dominant order through inactivity. If he’s asked to complete a mindless task, he simply doesn’t do it and if asked to explain his actions, he replies in witticisms. It isn’t until he is continually denied a department budget that he takes some action. Unable to go on telling his full-time and part-time department to “keep waiting” to hear if they still have jobs, he takes advantage of the presence of a television news crew on campus to cover an unrelated event. After getting the news anchor’s attention, he grabs a goose wandering around the pond in the quad and promises to kill one goose for every day he is made to wait for his budget. He eventually gets his budget, but is voted out as department chair, and is made to watch as the college struggles against budget cuts made by administrators who buy books they never read and never plan to read in bulk just to fill the shelves in their offices. He takes on the role of picaresque rebel and decidedly small literary hero.

Richard Russo writes about a Vin-like character in his novel Straight Man. The protagonist is William Henry Devereaux Jr., the reluctant chairman of the English department of a badly underfunded college in Pennsylvania rust belt. Devereaux, like Vin, is quiet, stays out of people’s way, and does his best to remove himself from the boring and small-minded affairs of academic committees and in-fighting. He also doesn’t take any shit, and like Vin rebels against the dominant order through inactivity. If he’s asked to complete a mindless task, he simply doesn’t do it and if asked to explain his actions, he replies in witticisms. It isn’t until he is continually denied a department budget that he takes some action. Unable to go on telling his full-time and part-time department to “keep waiting” to hear if they still have jobs, he takes advantage of the presence of a television news crew on campus to cover an unrelated event. After getting the news anchor’s attention, he grabs a goose wandering around the pond in the quad and promises to kill one goose for every day he is made to wait for his budget. He eventually gets his budget, but is voted out as department chair, and is made to watch as the college struggles against budget cuts made by administrators who buy books they never read and never plan to read in bulk just to fill the shelves in their offices. He takes on the role of picaresque rebel and decidedly small literary hero.

Vin, Devereaux, and The Dude. These are the kind of heroes that the University of St. Francis, Joliet, and America needs as the economy continues to plummet, communities continue to tear, and the country’s governing institutions continue to exercise tragic absurdity. The country will need people who demonstrate an alternative method of living and behaving, not by demonstrating delusion and engaging a broken system, but by acting out of the system as examples of quiet, committed protests of lifestyle. As Zizek points out about Bartleby, the very existence of people such as him briefly, but powerfully, suspend the vicious cycle of an unfair and unjust dominant order. Bartleby does not say “I don’t want to” as his protest, but rather “I prefer not to.” In other words, “I want to not…” It is a positive statement of affirmation—an example of empowering passivity as opposed to paralyzing apathy.

Vin, Devereaux, and The Dude. These are the kind of heroes that the University of St. Francis, Joliet, and America needs as the economy continues to plummet, communities continue to tear, and the country’s governing institutions continue to exercise tragic absurdity. The country will need people who demonstrate an alternative method of living and behaving, not by demonstrating delusion and engaging a broken system, but by acting out of the system as examples of quiet, committed protests of lifestyle. As Zizek points out about Bartleby, the very existence of people such as him briefly, but powerfully, suspend the vicious cycle of an unfair and unjust dominant order. Bartleby does not say “I don’t want to” as his protest, but rather “I prefer not to.” In other words, “I want to not…” It is a positive statement of affirmation—an example of empowering passivity as opposed to paralyzing apathy.

Vin sits in his office—one of the only faculty offices with a bathroom, which he nabbed by putting in a reserve for it when he heard rumors that the professor who had it before him was leaving—surrounded by books of Dostoevsky, on St. Francis, and about radical philosophy. He looks at a large picture of him and his wife in Lithuania and a statue of Jesus, with his loafered feet resting on his desk, and he doesn’t convince himself that he is inciting a revolution or that he is of greater moral virtue to average Americans because of his level of education, which is superior to most Americans. He knows he is part of an institution with a solid ethical and education foundation, but an ambiguous future, and he seeks—through his courses, conversations, and mere existence—to be a reminder of something different, yet familiar—something different from the direction things are headed and different from the winning notion that the business model is the best model for higher education. He’s his own man and he’s connected to a different tradition and that is enough, because perhaps he can inspire other individuals who would like to preserve individuality through the dedication to a higher purpose of community and spirituality. Devereaux did not give administrators the epiphany that cutting humanities is a betrayal of the purpose of a liberal arts education, just as The Dude did not rescue Southern California from the hands of greedy, selfish, and corrupt corporate elites. What they did was give those within view and earshot evidence that the way the world is run is often fucked up, and that the individual does not have to be a participant.

Vin sits in his office—one of the only faculty offices with a bathroom, which he nabbed by putting in a reserve for it when he heard rumors that the professor who had it before him was leaving—surrounded by books of Dostoevsky, on St. Francis, and about radical philosophy. He looks at a large picture of him and his wife in Lithuania and a statue of Jesus, with his loafered feet resting on his desk, and he doesn’t convince himself that he is inciting a revolution or that he is of greater moral virtue to average Americans because of his level of education, which is superior to most Americans. He knows he is part of an institution with a solid ethical and education foundation, but an ambiguous future, and he seeks—through his courses, conversations, and mere existence—to be a reminder of something different, yet familiar—something different from the direction things are headed and different from the winning notion that the business model is the best model for higher education. He’s his own man and he’s connected to a different tradition and that is enough, because perhaps he can inspire other individuals who would like to preserve individuality through the dedication to a higher purpose of community and spirituality. Devereaux did not give administrators the epiphany that cutting humanities is a betrayal of the purpose of a liberal arts education, just as The Dude did not rescue Southern California from the hands of greedy, selfish, and corrupt corporate elites. What they did was give those within view and earshot evidence that the way the world is run is often fucked up, and that the individual does not have to be a participant.

David Masciotra is the author of Working On a Dream: The Progressive Political Vision of Bruce Springsteen (Continuum Books). For more information visit www.davidmasciotra.com

It’s late so I can’t finish reading this right now, but I will look forward to finishing it in the morning. This looks really good, dude, if I understand it correctly.

A really touching tale of what sounds like a great man. I’m quite interested in reading the rest of the book, considering the subject.

I really like the inclusion of these new concepts to me, such as the Bartleby Politics, and that wonderful quote from Addison Hart that puts into words something I’ve always felt. Going to bandy that one about from now on where appropriate :)

A definate education from Dude University, I’ve had today!

A thoroughly enjoyable and inspirational essay! It’s really sad how colleges are fast becoming over-priced job training centers and liberal arts/humanities are seen as valueless and a waste of time. As a newly employed pizza-delivery driver, I’m finding my B.A. in philosophy to be a priceless investment, although I can’t really say exactly why…

A great prophetic essay.The british educational system has become equally flawed by capitalism.

Finally got a chance to finish this.

I really dig your style, man. Lots of strands going through my head now after reading it.

As someone from the working poor who went to college, I really appreciated your comments on the disconnect between academia and working class resonated with me.

Overall, though, I think your portrait of Vin shows us all how important it is to abide, especially these uptight days. It may seem like we’re doing nothing, but as Vin’s impact on you demonstrates, our abiding example has ripple effects on others that we may never know or see directly.

Sorry that second sentence was a bit blathering in nature. Lost my train of thought…

“As someone from the working poor who went to college, I really appreciated your comments on the disconnect between academia and working class; they resonated with my undergrad experience.” That’s closer to what I was thinking.

Hands down one of the best articles I’ve read on this. Great, great ideas very well written. It added Vin to my list of modern day heroes, a list that includes Derek Sivers (http://sivers.org/blog). An excellent example of how to counter a corrupt and failed system by staying outside of it. Kudos to Marvin Katilius-Boydstun for setting such a fine example and to David Masciotra for sharing it!

Great article. Lots of fresh, zesty ideas for us to mull around on while we have our feet on a desk, drinking an oat soda and contemplating life in a quiet, non-violent fashion. People like Vin are a nice counterbalance to all the paraquats out there today. I’m waiting to read more from David.

I dig it man. Here’s to the Vin’s of the world… may they give the facists ulcers.

Wow, this is such a fantastic article. Reading this I was constantly being reminded of professors I have now who fit the descriptions of every type mentioned. I’m going to graduate school to be a higher education administrator, and I plan to be similar to Vin in every way I can.

Great article. Wish I could meet Vin.