Roy Hamric interviews poet Jim Harrison

Roy Hamric interviews poet Jim Harrison

[Originally published in the Kyoto Journal as “A Pilgrim in the Void”]

By Roy Hamric

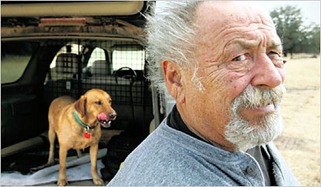

One of the most accomplished poets in American letters, Jim Harrison, who lives in Livingston, Montana, has written ten books of poetry, eleven novels, five novella collections, four nonfiction books and dozens of screenplays.[1] Movies based on his books or original screenplays include Legends of the Fall, Wolf, Revenge, Farmer and Dalva.

Harrison, a brilliant conversationalist, is known for his vitalism, elan, and love of Nature. He is among a group of American poets who have created work that shares the spirit of Asian masters, probing the mysteries of consciousness and savoring the natural world.

A longtime student of Zen, Harrison shares the exuberant independence of Ikkyu, the loner qualities of Han Shan (Cold Mountain) and the sophistication of Su Tung p’o, all entwined in his unique American spirit which early on was influenced by Emerson and Thoreau, the dominate masters of American nature and “consciousness” writing. He once described the thread running through his writing as, “The individual soul struggling for a life that’s more abundant.” No American poet since Whitman has probed and celebrated their life more robustly and perceptively than Harrison.

ROY HAMRIC: In your twenties, you had a brief academic career. You were recognized as a poet and potential scholar with a bright future. You had ambivalent feelings?

JIM HARRISON: My academic career was truncated partly because good universities are in the wrong places. I only feel comfortable physically in rural or relatively remote places. At one point I flunked out of graduate school. At Stony Brook I was asked by a New York publisher, I think it was Knopf, to do the official biography of William Carlos Williams but such a project was alien to my temperament. I recall when I was about 25 sitting in Charles Olson’s apartment up near Groton’s very smelly fish business in Gloucester. He admonished me to only traffic in my own sign.

JIM HARRISON: My academic career was truncated partly because good universities are in the wrong places. I only feel comfortable physically in rural or relatively remote places. At one point I flunked out of graduate school. At Stony Brook I was asked by a New York publisher, I think it was Knopf, to do the official biography of William Carlos Williams but such a project was alien to my temperament. I recall when I was about 25 sitting in Charles Olson’s apartment up near Groton’s very smelly fish business in Gloucester. He admonished me to only traffic in my own sign.

Did you relate to the Beat generation writers, or did you feel outside that scene? You were 19 when On the Road appeared.

Well, at 19 I felt a certain sympathy with Beat writers. I was a restless soul and did a great deal of hitchhiking around America. I was lucky to have talked with Kerouac several evenings at the Five Spot in New York right after On the Road appeared. I don’t suppose I was ever part of any "scene" as such.

How did the poetry of Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg affect you, in your formative stage and later as a mature poet?

I read all the work of Kerouac, Snyder, and Ginsberg early on and continued to keep up with them. Kerouac and Ginsberg waned for me but Snyder had staying power likely for temperamental reasons, a similarity in backgrounds. For instance yesterday in the mountains I saw seven very wild bighorn sheep. I felt intense pleasure.

Which earlier poets most influenced you and how?

Which earlier poets most influenced you and how?

I’ve always been an obsessive reader of world poetry since the age of 14. Early obsessions were Whitman, Rilke, and Lorca, and the French Symbolists, especially Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Actual influence is another matter. There were so many I have no idea. I was in my teens when Ezra Pound turned me to the Orientals and they never left me.

Rilke and Yesenin are two strong poetic precursors. What’s the key to their power for you?

Yesenin’s influence was a matter of temperament. He was a country boy who had bad luck with urban life. It was a bad match. Rilke’s power over me has waned because of what I see as his implicit narcissism and a gift for abstraction I have lost in the process of getting older. For instance I used to think I understood Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (at age 14!) and The Heart Sutra. Now both of them have left me far behind compared to my comprehension of red wine and garlic.

How influential were Emerson and Thoreau?

Emerson and Thoreau were curiously enough part of our big family in my childhood. My father was obsessed with Thoreau though he treated him with some humor. Nothing has more ill-equipped me for modern life than my early study of Emerson. I wrote in a recent comic novel, The English Major, that Emerson ought to have a product warning label on his books. How do you work for SONY if you’ve studied Emerson? Well, I did in Hollywood in a schizophrenic stage of my life.

Do you think there’s sufficient appreciation of Emerson and Thoreau–– the way they established what is really an American dharma esthetic based on a “consciousness practice” and deep relationship with Nature?

I of course don’t think there’s a sufficient appreciation of Emerson and Thoreau, but then such things are quite hopeless. It sleepily exists in the American literary canon and then I suppose it gradually emerges, as it did in my own family. It’s notable that both Emerson and Thoreau strike me as so Oriental. When I was studying the Haida Indians I noted that their liturgy was obviously pre-Buddhist Chinese. I’ve often wondered at the fact that so many of our western natives came over the Aleutian land bridge and that this liturgy has become part of the land. This is a spooky and not-really-rational idea, but then even Karl Jung believed that our dreams emerge from the landscape.

You often quote Lawrence, who said, “The only aristocracy that matters is that of consciousness.” Emerson and Dogen both talked about kindling the mind, the “mind on fire.”

Yes, I suspect that D.H. Lawrence, Emerson and Dogen were talking about the same thing. The Lawrence quote is kind of a koan. Ultimately everything is led by mind, and Lawrence was pointing out that consciousness is about all that we can own. I think of Lawrence as a relentless reminder that time is short, so why limit our consciousness?

Your actual writing method shares similarities with Ginsberg’s and Kerouac’s idea of “first thought, best thought,” right? The story is that you wrote Legends of the Fall straight through in nine days and only revised one sentence. Do you try to use that technique in both fiction and poetry?

Your actual writing method shares similarities with Ginsberg’s and Kerouac’s idea of “first thought, best thought,” right? The story is that you wrote Legends of the Fall straight through in nine days and only revised one sentence. Do you try to use that technique in both fiction and poetry?

Well, I’m quite different from Ginsberg and Kerouac. Yes, Legends of the Fall came in one piece, but I had brooded about the story for a decade. I think of my mind as an "image bank", from which I draw. Consequently the actual composition time might be relatively short because the novel is essentially written in my brain. We have to keep remembering that Wallace Stevens said "Technique is the proof of seriousness." If I have spent 50 years as a writer, presumably I know how to write, so when lightning strikes I’m immediately capable of rendering the lightning.

You once said, “The gift of fiction is to make life live itself.” What is the gift of poetry?

I think it was Heidegger who said that poetry is not elevated common speech, common speech is poetry in severe decline. I recall in Julian Jaynes’ book on the mind, people used to think they were actually talking to the gods, with no irony attached. Rilke said one reason we write poems is to keep the gods alive. The gift of poetry is that it is the first and most primal art form, which gathers together our most valuable feelings.

There’s a branch of American poetry with a strong kinship to Asian poetry and sensibilities, in the tradition of the Buddhist poets of China and Japan.

There’s a branch of American poetry with a strong kinship to Asian poetry and sensibilities, in the tradition of the Buddhist poets of China and Japan.

The U.S. is several countries. There is the eastern seaboard with its peculiar geopieties, but in the Midwest (Bly and his wonderful crew) and the west the traditions of Japanese and Chinese poetry are everywhere apparent.

You and Ted Kooser produced a terrific book of short, pungent poems, Braided Creek, an exchange of Asian flavored poetry equal to anything in China or Japan. Each poem is anonymous.

Braided Creek is partly a testament against personality which becomes tiresome indeed, a Romantic throwback. I care for the poem, not who wrote it. Of course you can’t actually write haiku in English so we certainly didn’t call them that. I have no interest in nationalistic aspects of poetry. It reminds me of the Tennyson-Kipling foghorn. Kooser is one of the best read poets I have ever met and I suppose we were sharing the influence of Japanese and Chinese poets in our lives.

There’s a greater taste of Zen and Chinese poetry in your last four poetry books, which cover a 22-year period. Your stance seems to come from a more moment-to-moment, centered voice with a “letting go” feeling akin to the wisdom of old hermits.

We shrink into what we truly are with age. For instance in the late work of Antonio Machado you could pass some poems off as Oriental. We gather ourselves then disperse the non-essential parts. My reading of Dogen was ill-digested because of my limitations but I came to understand that the self gets in the way except as a literary construct, a form for the voice.

Who are your favorite Chinese and Japanese poets?

I don’t have favorite poets per se. I have hundreds that I read with interest and full attention. For instance, this morning on waking I was reading Jonathan Chaves exquisite work on Yang Wan-Li, and also Norman Waddell’s fine new book on Baisao. Of course certain poets have overwhelmed me whether Ikkyu or in recent years Su Tung-p’o.

Is there any hope for a contingent of critics who seem not to understand the role and power of the ordinary in poetry? They sometimes twitter at your homey, everyday subject matter and observations.

Is there any hope for a contingent of critics who seem not to understand the role and power of the ordinary in poetry? They sometimes twitter at your homey, everyday subject matter and observations.

No, there’s no hope. Such critics are victims of the bad aspects of the French Enlightenment which places man far above the ordinary despite the fact that that’s where he lives. Right now in my life I can only read two critics: Roberto Calasso and George Steiner.

Talk about your Zen practice and specifically some events that were instrumental in leading you to where you are today. First, what books most influenced your Zen practice early on?

My Zen practice is a total hoax though I’ve been involved nearly forty years. I’m just a poet and a novelist. My first germinal influences were D. T. Suzuki, the scholar, and Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.

Who were the people who influenced you in the early stages?

The problem was that I lived far from any zendo and early on had little traveling money. My influences were friends Dan Gerber and Bob Watkins who were students of Sensei Kobun Chino, and later Jack Turner, a student of Aitken Roshi and Nelson Foster.[2] Also my friendship with Peter Matthiessen which began to burgeon in the sixties along with my friendship with Gary Snyder. All along the way the critical factor was reading the translations of Burton Watson, Cid Corman, Willis Barnstone, Red Pine, Rexroth, Sam Hamill, or early anthologies like White Pony, or Sunflower Splendor and finally the brilliant The Roaring Stream edited by Nelson Foster and Jack Shoemaker.

What was your relationship with your teacher Sensei Kobun Chino like?

What was your relationship with your teacher Sensei Kobun Chino like?

I don’t think I met with Sensei Kobun Chino more than a half dozen times. I think Kobun was amused by my general disrepair. Of all the Zen men I’ve met Kobun had the most intricate and conclusive understanding of literature. He gave me a medallion of Achala because I kept falling off the log into the fire, crawling back on the log, and then falling back into the fire again. I still find myself mourning him and have had several dreams of Kobun and his daughter as adult and sub-adult ravens rising skyward from the lake in which they drowned. I sat with Kobun and Dan Gerber for a full stick of incense in a snow bank at the grave of D.H. Lawrence.

How does Peter Matthiessen fit in?

Early on I determined that Peter Matthiessen and Gary Snyder were the modern writers who knew how to live. Every year Peter comes to Montana and we fish floating down an immense river in a drift boat watching the prodigious bird life.

You once described your Zen practice as “nickel-plated,” and said you now prefer Zen-flavored poetry to abstract texts.

As I said, the ability to deal with abstract texts has fled my mind. I mean “nickel plated” in terms that by any conceivable test I’m a failure as a Zen student. In Dogen’s terms, I’m missing key ingredients for cooking my life.

Do you have a regular zazen practice today?

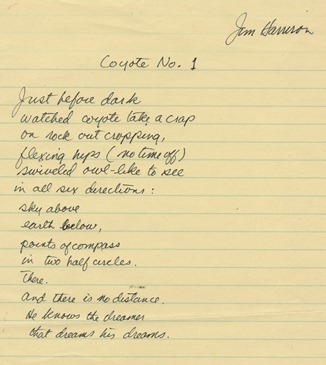

I’m not sure about regular Zen practice. It’s either central to your life or isn’t. I’ve been dealing with the same two koans for twenty years. For 25 years I had a remote cabin and throughout the vast landscape I had a dozen stumps and thickets for my daily sitting. We had a tiny retarded cat who used to sit on my head and sleep during zazen. I asked Kobun if this was okay and he said “fine.” What there is of my practice begins with reading poetry and then walking.

Walking, or wandering, is an honored form of spiritual communion for many hermits and poets, from Han Shan (Cold Mountain) to Wordsworth.

Walking tells you where you are. Dogen said “When you find yourself where you already are practice occurs.” The language of dogs and birds teaches you your own language. I think of reality as the aggregate of the perceptions of all creatures. It’s important for me to understand that I’m no more important than a bird. Walking is walking. We’re bipeds. Everything of value is informed by spirit. The Navajo bow to the directions on waking. I walk. For truly bad weather I have a zafu from which I’ve tipped over sideways several times when thinking about women or food.

Talk about your Livingston Suite of poems, which fit neatly into this category of exploring by foot. Did they come quickly?

Poems can’t be thought of to come quickly when you’ve spent 50 years on them. Of course sometimes in the actual composition it feels like you’re taking dictation.

Ikkyu was your most overtly Zennish poetry up to that time. Ikkyu, in his own time, in fact, shared your sensibilities in regard to throwing out orthodoxy and cant. Talk about the style of your poems in Ikkyu and how they came about.

With Ikkyu I was only having a conversation with an ancient friend whose spirit paid an extended visit. I can’t maintain interest in any institution, Zen or otherwise. I’m a mammal not a citizen.

Your new book In Search of Small Gods is a continuation of these themes. Does poetry come to you easier now?

Your new book In Search of Small Gods is a continuation of these themes. Does poetry come to you easier now?

In In Search of Small Gods the actual writing was peculiar. I figured out that riding on planes was bad for my poetry so I didn’t do it for five months during which most of the book was composed. The process of a poem is always harrowing. Wang Wei said something to the effect that who knows what causes the opening and closing of the door?

You’ve lived with The Muse for 50-odd years. Do you have a better understanding now of how the unknown works in your creative life?

You think you understood the process better but this is possibly an illusion because your understanding can’t cause a poem. The muse, the daemon, doesn’t care if you’re a trashy old drunk vomiting blood.

Was writing novels a second choice––your fiction voice is one of the most identifiable in literature. You and your friend Thomas McGuane both rely on consistent irony as a ballast to describe our contemporary world.

I don’t know if fiction was a second choice. It all happens at once. I don’t separate the genres. Both are who I am. Irony is a tool to pry off the heavy lid that the culture places on life.

People are curious about the correspondence you and McGuane have kept up for more than 40 years. You’ve said it’s mostly about literary matters. Can we expect to see some of it published soon?

We’ve talked about publishing our correspondence but it will likely stay under wraps as too much of it is of a personal nature.

Do you have abundant correspondence with other poets?

I’ve corresponded with a great number of poets. I even have a letter from Robert Duncan that he wrote while sitting up with Charles Olson the entire night that Olson died. Right now I have a weekly fax correspondence with Ted Kooser and Dan Gerber.

In your teens, you overflowed with religious feeling. Truly spiritual matters are approached condescendingly or somewhat intellectually in most contemporary American fiction, yet the critic Harold Bloom says the spiritual search fuels poetry.

In your teens, you overflowed with religious feeling. Truly spiritual matters are approached condescendingly or somewhat intellectually in most contemporary American fiction, yet the critic Harold Bloom says the spiritual search fuels poetry.

Well, of course. What motive could there possibly be except the spiritual? Poetry is a calling. It’s wildly undemocratic. “Many are called but few are chosen,” it has been said. I’m unfamiliar with Harold Bloom except for his book on Blake. I could find no room for myself in organized religion so I created my own that changes somewhat moment by moment as it should. I’m just another of billions of pilgrims in the void.

I offer a small satori poem:

BARKING

The moon comes up.

The moon goes down.

This is to inform you

that I didn’t die young.

Age swept past me

but I caught up.

Spring has begun here and each day

brings new birds up from Mexico.

Yesterday I got a call from the outside

world but I said no in thunder.

I was a dog on a short chain

and now there’s no chain.

~ Jim Harrison

Footnotes:

1. Harrison’s poetry books include Plain Songs, Locations, Outlyer and Ghazals, Letters to Yesenin, Selected and New Poems, The Theory and Practice of Rivers, After Ikkyu and Other Poems, Braided Creek, Saving Daylight and In Search of Small Gods.

2. Sensi Kobun Chino was a Soto Zen Master who founded the Hokoji Zendo in Taos, New Mexico. He drowned in a pond in 2002 in Switzerland while trying to save the life of his daughter, Maya, who also drowned. Harrison has a cabin in New Mexico where he lives during the winter months.

Visit Roy’s blog at www.royhamric.wordpress.com

from Eleven Dawns with Su Tung-p’o

9.

Late in life I’ve lost my country.

Everywhere there is the malice of unearned

power, top to bottom, bottom to top,

nearly solid scum. Very few can read or write.

Lucky for me we winter in this bamboo thicket

near a creek with three barrels of bird food.

With first light things seem a little better.10.

Don’t probe your brain’s sore tooth in the dark.

Let your mind drift to the mountains

where migrants are doubtless freezing

on the coldest night of the year. The dogs

found a nest beneath the roots of a big sycamore

tipped over in July’s flood. The ashes of a tiny fire,

an empty water bottle, a pop-top can of beans

scorched by the coals. These dangerous people

whom we’re being taught to hate like the Arabs.

From Braided Creek

Jim Harrison and Ted Kooser (US poet laureate)

Only today

I heard

the river

within the river.

*

An empty boat

will volunteer for anything.

*

I have used up more than

20,000 days waiting to see

what the next would bring.

*

Today a pink rose in a vase

on the table.

Tomorrow petals.

From Ikkyu

29

The four seasons, the ten oaths, the nine colors

three vowels

that stretch forth their paltry hands to the seven

flavors

And the one money, the official parody of prayer.

Up on this mountain, stumbling on talus, on the

north face

there is snow, and on the south, buds of pink flowers.54

This morning I felt strong and jaunty in my mail

order

Israeli commando trousers. Up at Hard Luck Ranch

I spoke

to the ravens in baritone, fed the cats with manly

gestures.

Acacia thorns can’t penetrate these mighty pants,

then out

by the corral the infant pup began to weep,

abandoned.

In an instant I became another of the Earth’s billion sad

mothers.

i like 54.

Marvelous interview and trenchant comments. Have you seen Zen painting?

Marvelous interview and trenchant comments. Have you seen Zen painting?

Interesting interview, what I wouldn’t give to spend an hour or two with him, though I fear I wouldn’t have anything interesting to say…’Barking’ is a poem to read and reread

Marvelous!!! Please send me more of whatever you do,d

I attended a lecture by Jim Harrison several years ago in Hailey, Idaho. He was visiting because the birthplace of Ezra Pound is in Hailey. He read some of his favorite poems, talked about his writing process and entertained questions from the audience. He graciously signed a stack of books I presented to him after the lecture. If you ever have a chance to see him in person do not miss it!

Mr. Harrison’s cabin was in Arizona.