Given the fact that the term “dude” has become so all-encompassing in popular language, used in every grammatical form possible from noun (“dude”) to exclamation (“dude!”) to greeting (“duuuude”) to expression of awe (“doooood!”), it’s hard to believe that a mere quarter of a century ago, the word was largely unheard outside of urban black communities.

In fact, outside of the ghetto in the 1970s, the term dude may have been partially associated with homosexuality as evinced by a popular David Bowie/Mott the Hoople glam-rock song (“All the young dudes”) and the legacy of the original "dandy" dude (see this older Dudeism article on dude etymology).

So how did “dude” become such an integral part of modern pop culture? It traveled via a curious vector, through a subculture that has been long-admired but little-understood, a quasi-religious fraternity of dropouts that prefigured much of modern Dudeism. I refer, of course, to the Surfer Dude. Had it not been for this itinerant band of fluffy-headed wave-chasers, our current conception of “the dude” would have likely involved a mix of Shaft (the famous blaxploitation movie featuring Richard Roundtree as a violent urban private eye) and shafting. Thus, it might not have become the widespread and all-encompassing term it is today.

Although surf culture had been around since the early 1960s, a result of Hawaii becoming an official state of the U.S. in 1959, it didn’t really become a big part of popular culture until the 1980s.

Although surf culture had been around since the early 1960s, a result of Hawaii becoming an official state of the U.S. in 1959, it didn’t really become a big part of popular culture until the 1980s.

The seminal moment in which the Surfer Dude emerged, like Venus, from the ocean of mythos can be traced to the 1982 film Fast Times at Ridgemont High. In this critically-panned cult-smash, a then-unknown Sean Penn played a perpetually stoned high school student named Jeff Spicoli – one of those cultural torchbearers, like Shakespeare, Derrida, or Snoop Dog, who change the way we think about language and meaning forever.

The setting for much of the movie was perhaps the most high-profile shopping mall in the United States at the time – the Sherman Oaks Galleria, a site featured in a host of other 80s films as well, and notably in Frank Zappa’s hit novelty song “Valley Girl.”

This mall was an apt setting for a cutting-edge youth flick, as it helped usher in a new zeitgeist for youth culture in that decade. It was in the gleaming neon-lit shopping center that upwardly mobile mainstream American kids flocked to on weekends to play video games, secretly smoke cigarettes and talk about sex.

This mall was an apt setting for a cutting-edge youth flick, as it helped usher in a new zeitgeist for youth culture in that decade. It was in the gleaming neon-lit shopping center that upwardly mobile mainstream American kids flocked to on weekends to play video games, secretly smoke cigarettes and talk about sex.

As a result, the outdoors were increasingly coming to be seen as something old-fashioned. The beach especially, while occasionally visited to touch-up one’s tan, was deemed a lame place to spend too much time. Not only was the beach where homeless people lived, but outside of bad food, there was nothing to buy. Moreover, unless you wanted to catch a skin disease, you certainly didn’t go swimming in its polluted surf.

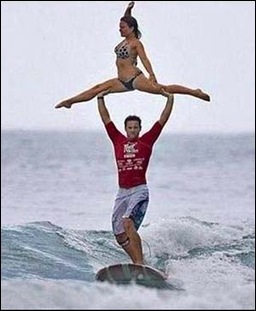

To another breed of youth culture, however, the beach was the best place on earth. Though chastised for being lazy, “surfers” woke regularly at dawn to ride the best waves on fiberglass planks, and did so for hours, sometimes missing a few hours of school to do so. Unlike their mall-bound contemporaries, instead of flying in a spaceship on a videogame screen they flew over the ocean in real life. Instead of smoking cigarettes they smoked weed. And instead of talking about having sex, they actually had it.

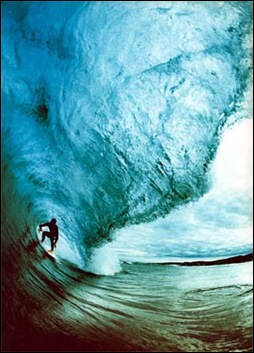

In one of Fast Times at Ridgemont High’s most telling scenes, Jeff Spicoli is interrogated by a hardworking, ambitious, and rather pathetic character named Brad, who manages the local convenience store. Spicoli is fishing around in his pocket for change to pay for a donut to go with his can of fruit juice. “Why don’t you get a job, Spicoli?” Brad demands. “What for?” a surprised Spicoli answers, to which Brad retorts: “You need money!” Spicoli breaks out in a big grin and utters his now-famous philosophy: “All I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine.” He may not get the donut, but he’s got everything else, and he’s happy enough. Shortly afterwards, Spicoli saves Brooke Shields from drowning and then blows all the reward money by hiring the rock band Van Halen to play at his birthday party.

In one of Fast Times at Ridgemont High’s most telling scenes, Jeff Spicoli is interrogated by a hardworking, ambitious, and rather pathetic character named Brad, who manages the local convenience store. Spicoli is fishing around in his pocket for change to pay for a donut to go with his can of fruit juice. “Why don’t you get a job, Spicoli?” Brad demands. “What for?” a surprised Spicoli answers, to which Brad retorts: “You need money!” Spicoli breaks out in a big grin and utters his now-famous philosophy: “All I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine.” He may not get the donut, but he’s got everything else, and he’s happy enough. Shortly afterwards, Spicoli saves Brooke Shields from drowning and then blows all the reward money by hiring the rock band Van Halen to play at his birthday party.

Clearly, unlike all the other neurotic adolescents in the film, Spicoli was not a fellow who worried too much. Most of all, he knew how to go with the flow, something any avid surfer instinctively knows how to do. After all, though you’ve got to catch the wave just at the right time, you’ve also got to wait for it. Until the opportunity arrives, paddling around like a moron will get you nowhere. Though Spicoli may not have been terribly clever, his rejection of dogmatism and celebration of the spirit revealed him to be the wisest, most joyful character in the whole angst-ridden movie. He was certainly the only one worth emulating, and the only one avidly quoted.

Although the stereotype of the surfing lifestyle may seem fairly superficial, surfing as a pastime is in fact deeper than it looks. It may in fact be one of the most philosophical sports around, being long associated with various aspects of spirituality. The long running surf shop, Town and Country incorporated the Yin Yang symbol as its logo before most of the new age community even knew what it was. Christian surf clubs have popped up all over the US, Australia and elsewhere. There’s even a famous and popular “Surfing Rabbi” who wrote a book on the connection between religion and surfing and holds kosher surf camps in Costa Rica.

Although the stereotype of the surfing lifestyle may seem fairly superficial, surfing as a pastime is in fact deeper than it looks. It may in fact be one of the most philosophical sports around, being long associated with various aspects of spirituality. The long running surf shop, Town and Country incorporated the Yin Yang symbol as its logo before most of the new age community even knew what it was. Christian surf clubs have popped up all over the US, Australia and elsewhere. There’s even a famous and popular “Surfing Rabbi” who wrote a book on the connection between religion and surfing and holds kosher surf camps in Costa Rica.

Surfers are often instinctively spiritual, drawn to the union with nature and peace of mind that surfing provides. As one Christian surfer put it in a 2005 New York Times article, “The world is getting gnarlier and gnarlier. You get drawn into God with surfing…[it] teaches selflessness.” Yet most surfers, being outsiders at heart, are wary of organized religion. Which leads one to wonder, if surfing already has the congregation and the church, why bother associating it with established creeds? One famous Australian surfer, Nat Young, in fact tried to register surfing itself as an official religion, though his government didn’t recognize it.

Yet there is hope: Surfers out there looking for religion, but loath to sign up with the commercialized multinationals, would do well to consider Dudeism. For Surferism is merely sun-drenched Dudeism in disguise. It’s no accident that the film which has elevated Dudeism to its current status, The Big Lebowski, ends with a eulogy for a fallen character, in which it is revealed that he was actually a surfer in bowler’s clothing: the filmmakers are evidently paying respects to the surfers who gave “dude” its due, by broadening the concept and distributing it to the masses.

Yet there is hope: Surfers out there looking for religion, but loath to sign up with the commercialized multinationals, would do well to consider Dudeism. For Surferism is merely sun-drenched Dudeism in disguise. It’s no accident that the film which has elevated Dudeism to its current status, The Big Lebowski, ends with a eulogy for a fallen character, in which it is revealed that he was actually a surfer in bowler’s clothing: the filmmakers are evidently paying respects to the surfers who gave “dude” its due, by broadening the concept and distributing it to the masses.

Whereas “dude” had heretofore been a term to suggest either high social standing, or a mockery of that status, surfers united the disparate strains of “dude” (fastidious dandy, macho poseur, stoned rocker, nature-seeking elitist) via an all-encompassing arch irony in which all ego and social hierarchies were collapsed against the face of nature, the awesome yet fortifying power of the surf.

Though “water” has been an overused, often banal metaphor for everything, it is not so in this case. The Tao Te Ching frequently alludes to water as the most powerful of all things, the fundament of our being, a force that ultimately overcomes all man-made constructions. That great Dudeist novelist, Kurt Vonnegut put it well: In comparison with the awkwardness he suffered in civilized, landlocked life he mused, “In the water, I am beautiful.” Yet he was only talking about swimming pools.

Stripped of our burdens in the mighty ocean, naked and free, we are more than beautiful: We are dudeiful.

Any biologist will tell you – our origin is in the ocean, and we in fact carry that ocean within us today, the saltwater reservoirs inside our bodies.

Some evolutionary theorists convincingly argue that humans even had an extended “aquatic” phase in which we lived in the shallow waters of a large lake in present-day Ethiopia. If true, it’s no wonder that holidaymakers choose the beach above all other destinations: the ocean is our atavistic Eden. Surfers helped remind us of this, and with their peaceful, laissez-faire attitude also played an important counterpoint to the increasing commercialization and aggressive ideals of the late 20th century.

Some evolutionary theorists convincingly argue that humans even had an extended “aquatic” phase in which we lived in the shallow waters of a large lake in present-day Ethiopia. If true, it’s no wonder that holidaymakers choose the beach above all other destinations: the ocean is our atavistic Eden. Surfers helped remind us of this, and with their peaceful, laissez-faire attitude also played an important counterpoint to the increasing commercialization and aggressive ideals of the late 20th century.

“Dude,” the word they re-appropriated and redefined is their gift to us, a reminder that our vanities amount to nothing in the face of a “totally awesome” wave. The best we can hope to do is ride it out and try to have fun while doing so.

Cowabunga, an old surfer exclamation of joy and exhilaration when riding a monster wave, is another word their tribe contributed to the popular lexicon, and one which we should perhaps employ more often. One never knows which crest will be the last. Do not go gentle into that good wipeout. Cowabunga, dude.

Nice one Dudely! Has a nice wavy flow to ‘er. And let’s not forget Vonnegut’s Galapagos where he depicts the future human race as going back to the ocean and evolving flippers and such; A pretty Dudeist future and one I could only hope we collectively aspire towards. Seems only appropriate with the polar caps melting and ocean levels rising that we should get reacquainted with some tasty waves.

Dude for thought, man. I mark it 8.

Let’s not forget that Great Dude Mark Twain was among the first white guys to surf when he visited what’s now called Hawaii in the 1860s:

http://dudespaper.com/great-dudes-in-history-mark-twain.html/

“And like Donnie, Twain was a surfer — probably the first white guy, in fact, to surf the beaches of Hawaii. In his book Roughing It, Twain described his attempt at what was then called ‘surf-bathing’:

“In one place we came upon a large company of naked natives, of both sexes and all ages, amusing themselves with the national pastime of surf-bathing — I tried surf-bathing once, subsequently, but made a failure of it. I got the board placed right, and at the right moment, too; but missed the connection myself. The board struck the shore in three-quarters of a second, without any cargo, and I struck the bottom about the same time, with a couple of barrels of water in me.”

Well…he tried, anyway. :-)

Doooooode!, I am so impressed. I have been surfing my whole life. I can not remember ever calling anyone “dude”;however, I have heard it used by those we call kooks.

Good blog, I am going one better and giving it a 9.

Forgot the U in Dude, sorry.

Informitive piece of information on the etomology of use of the word Dude. I did not know. I hope to eventually catch up with all of these fine gentlemen’s contributions in The Dudes Paper for there appears to be much I did not know?

Well done Ollilama,

Mark Mac