Originally delivered on Sunday, January 13, 2008 at the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship at Easton (Maryland).

Opening Words

(Embellished version from Pulp Fiction)

Ezekiel 25:17—The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he that shepherds the weak from the valley of darkness for he is truly his brother’s keeper, and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers, and you will know my name is the lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.

Meditation: Psalm 103:15—As for man, his days are as grass; as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth; for the wind passeth over it and it is gone.

The Gospel According to the Hit Man and the Dude

The Gospel According to the Hit Man and the Dude

One of the few times I remember feeling any real sense of community when I was growing up was when my family and I went to the drive-in movies together. This was back in the early ‘70s when there were still plenty of these outdoor theaters around, especially in Southern California where we lived at the time.

If you’ve been to a drive-in you probably remember that it was a lot different than going to a multiplex is today. I remember it being cheaper, for one thing. My family didn’t have a lot of money…we didn’t have any money, really. Yet my mom could afford on her waitress wages to take my unemployed stepfather, my younger sister, and me regularly to an evening at the drive-in.

This included admission, popcorn, sodas, maybe even hotdogs and a box of Raisinets. Today, I almost have to take out a small loan just to so my family and I can see a matinee over at Easton Premiere Cinemas.

But there was something else that was special about going to a drive-in: the social aspect of it. I remember playing on the playground as the sun went down, adults chatting around their cars as the massive white movie screen grew silhouetted against the evening sky.

Then there was that moment in the twilight when the darkening screen erupted into colorful cartoons of those singing and dancing soda cups, hamburgers, and boxes of candy inviting you to visit the concession stand. You knew the movie would begin soon and everyone settled into their cars, kind of like we all settle into our seats here every Sunday when the worship leader rings the chime.

Then there was that moment in the twilight when the darkening screen erupted into colorful cartoons of those singing and dancing soda cups, hamburgers, and boxes of candy inviting you to visit the concession stand. You knew the movie would begin soon and everyone settled into their cars, kind of like we all settle into our seats here every Sunday when the worship leader rings the chime.

Strange as it may seem, when I look back on going to the drive-in, it was a lot like going to church is for me today. We didn’t attend a church at the time, so the drive-in was the closest thing I had to that kind of experience, anyway. There was the social aspect, as I mentioned, but at the heart of going to church or to a drive-in is the sermon like the one you’re listening to now, only the drive-in sermon was preached to us from a larger pulpit than the one before you now.

And unlike celluloid sermons, there probably won’t be any explosions or fistfights or romantic trysts during this sermon, but who knows? Life does frequently copy art.

I don’t mean to make a facetious comparison here between movies and church sermons. Depending on how you define “religion,” both a movie and a sermon can serve the same religious function in my mind. Many scholars believe the word “religion” derives from the Latin word ligo, which means “to bind together.”

I don’t mean to make a facetious comparison here between movies and church sermons. Depending on how you define “religion,” both a movie and a sermon can serve the same religious function in my mind. Many scholars believe the word “religion” derives from the Latin word ligo, which means “to bind together.”

Using this meaning of religion, a movie, like a sermon, can bind us together in the shared experience of celebrating certain values (some of which we may find offensive). Movies, like sermons, can offer us hope and reassurance, or confront us with profoundly disturbing questions. And like a sermon, movies have the power to enlighten or delude.

Entertainment has always been an integral part of religion. The ancient Greek comedies and tragedies were part of sacred civic ceremonies that unified Athens in a common cathartic experience. Medieval European morality plays, which evolved into Renaissance theater, promoted Christianity to a wide audience through drama. The theater played an important role in creating and perpetuating a communal identity.

According to John Belton, an English professor at Rutgers, movies play a similar function in modern America. He writes that because “there is no single myth or system of belief that ‘explains’ American identity” in our mass culture, movies serve to “assist audiences in negotiating major changes in identity; they carry them across difficult periods of cultural transition in such a way that a more or less coherent national identity remains in place.”

Like Aeschylus did with his tragedies or a minister does in a good sermon, the creators of movies reach into deep mythic pools for the raw material that underlies their narratives.

George Lucas in the Star Wars series, for example, draws from various world religions and folklore to create a mythology that reassures us a cosmic Force holds everything together in harmonious balance. Even a sci-fi movie with no apparent religious concern like Alien can explore unsettling existential questions about our place in an indifferent or hostile universe, just as Job does in the Bible.

George Lucas in the Star Wars series, for example, draws from various world religions and folklore to create a mythology that reassures us a cosmic Force holds everything together in harmonious balance. Even a sci-fi movie with no apparent religious concern like Alien can explore unsettling existential questions about our place in an indifferent or hostile universe, just as Job does in the Bible.

Even movies that some find offensive or dismiss as pointless can have at their center a life-defining worldview that audiences identify with. The two films I want to discuss today, Pulp Fiction and The Big Lebowski, are examples of such films. I should offer a caveat here before I begin, though. If you haven’t seen either film, I hesitate to recommend them.

Both films contain violence (especially Pulp Fiction), both have incredibly foul language, and both uncritically depict drug use and harsh or casual sex. Yet, in spite of such questionable content, I believe each of these cult classics preach important spiritual messages.

“Cult classic” is a perfect phrase for what I want to examine this morning. The word “cult”, of course, evokes a group of people devoted to religious beliefs outside the mainstream culture. Similarly, a “cult classic” is a movie that, for whatever reason, has brought together a subculture of highly devoted fans around it.

“Cult classic” is a perfect phrase for what I want to examine this morning. The word “cult”, of course, evokes a group of people devoted to religious beliefs outside the mainstream culture. Similarly, a “cult classic” is a movie that, for whatever reason, has brought together a subculture of highly devoted fans around it.

Since their release in the ‘90s, Pulp Fiction and The Big Lebowski have become quintessential cult classics. Both films have legions of loyal fans that watch them numerous times, memorize and recite lines, and, reminiscent of the faithful who bought religious relics from the medieval church, buy movie memorabilia—everything from T-shirts to action figures to reproductions of props used in the movies.

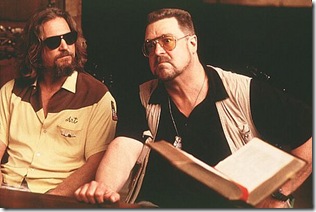

Fans of The Big Lebowski even make annual pilgrimages to “Lebowskifests,” where they dress up like characters and watch the film together. There’s also a quasi-religion centered around the movie’s main character, a slacker called the Dude (played by Jeff Bridges). According to the Church of the Latter Day Dude, adherents (of which I am one) preach non-preachiness, practice as little as possible, and follow the Dude’s admonition to just take it easy, man.

So what is it about these films that people find so deeply appealing? Pulp Fiction is basically just a film noir crime drama. Its fragmented, non-linear narrative follows the lives of a group of characters—including two hit men played by John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson—caught up in a seamy and violent world ruled by a crime boss named Marsellus.

So what is it about these films that people find so deeply appealing? Pulp Fiction is basically just a film noir crime drama. Its fragmented, non-linear narrative follows the lives of a group of characters—including two hit men played by John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson—caught up in a seamy and violent world ruled by a crime boss named Marsellus.

Although more difficult to define, The Big Lebowski is something of a takeoff on Raymond Chandler’s crime mystery The Big Sleep. But it’s also a tall tale of the old West with nihilism, eastern philosophy, bowling, pornography, and lots of foul language thrown in. To paraphrase the Dude, “This is a very complicated movie. You know, a lotta ins, a lotta outs, a lotta what-have-yous. And uh, lotta strands to keep in your head, man.”

Although Pulp Fiction won the Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival, some critics have dismissed it as a “terminally hip postmodern collage” of American nihilism. The Big Lebowski didn’t fare well with movie-goers or many critics initially. One critic accused it of being “too clever for its own good,” while even a sympathetic reviewer describes it as a mess, albeit a “glorious, wonderfully entertaining mess.”

Although Pulp Fiction won the Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival, some critics have dismissed it as a “terminally hip postmodern collage” of American nihilism. The Big Lebowski didn’t fare well with movie-goers or many critics initially. One critic accused it of being “too clever for its own good,” while even a sympathetic reviewer describes it as a mess, albeit a “glorious, wonderfully entertaining mess.”

Still, each movie has proven itself an enduring pop culture phenomenon. Pulp Fiction is regarded as one of the top 100 movies of all time and has inspired numerous copycat films, while The Big Lebowski is considered the first cult classic of the Internet era and continues to grow in popularity a decade after its initial disappointing release.

So the question remains: What is the staying power behind these movies? For me, the answer is found in what I said about the connection between movies and sermons. Underlying the vulgarity in these two films are the same theological themes—such as the possibility of redemption, the need for communion—that inspire homilies delivered from the pulpit.

Mark Twain’s satirical writings have been criticized for their violence and crudity, but Twain (who was himself a frustrated preacher) observed that his humorous narratives have endured because, at their heart, they are essentially literary sermons that preach and teach as well as entertain. Pulp Fiction and The Big Lebowski each, in their own cinematic way, do the same thing.

Mark Twain’s satirical writings have been criticized for their violence and crudity, but Twain (who was himself a frustrated preacher) observed that his humorous narratives have endured because, at their heart, they are essentially literary sermons that preach and teach as well as entertain. Pulp Fiction and The Big Lebowski each, in their own cinematic way, do the same thing.

It’s impossible for me to give a thorough discussion here of how these complex films accomplish this, but I will focus broadly on the theological themes I find in them, the themes that I believe either consciously or unconsciously resonate so deeply with their fans. Amid all the shooting, cussing, and general sordidness in Pulp Fiction, for example, runs a deep theological question that confronts at least two of its main characters, the hit men named Jules and Vincent.

It’s the same question Jesus confronted during his temptation in the desert, and that Buddha contemplated beneath the bodhi tree: are we to be defined by a fallen, corrupted world, or, like the hit man Jules discovers, is there something more meaningful to our lives than that—a higher, more authentic purpose?

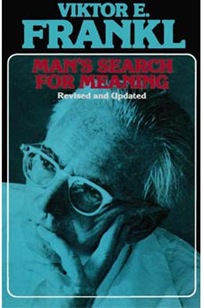

This is also a question that psychiatrist and Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl dedicated his life to resolving. During his time in the notorious death camp, Frankl observed that the prisoners who allowed their “inner hold on their moral and spiritual selves to subside eventually fell victim to the camp’s degenerating influences.”

This is also a question that psychiatrist and Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl dedicated his life to resolving. During his time in the notorious death camp, Frankl observed that the prisoners who allowed their “inner hold on their moral and spiritual selves to subside eventually fell victim to the camp’s degenerating influences.”

Jules the hit man finds himself in a similar degenerative world in Pulp Fiction. He inhabits a squalid, cruel underworld where life is cheap and one must brutalize others or be brutalized. In his service to the ruthless crime lord Marsellus, whose briefcase has a latch-lock combination that happens to be 666, Jules has made a satanic bargain in which he has lost his soul in order to survive.

Somewhere in his life, however, Jules was exposed to a different story than the lurid fiction he’s in. The passage I read today for our opening words is something Jules loves to recite. He says it’s Ezekiel 25:17, but it’s actually a jumble of prophetic voices from the Bible with the verse from Ezekiel as it main theme (according to one modern translation, the actual verse is much shorter: “I will take heavy vengeance on them, and when I carry out my vengeance they shall learn that I am Eternal”).

Wherever he originally heard the verse, it has lost its sacred value and now shows just how disconnected Jules has become from his moral and spiritual center. He likes to say the passage right before he kills someone because he believes it’s just a “cold-blooded thing to say.”

Wherever he originally heard the verse, it has lost its sacred value and now shows just how disconnected Jules has become from his moral and spiritual center. He likes to say the passage right before he kills someone because he believes it’s just a “cold-blooded thing to say.”

His identity as a hit man leads Jules to focus only on the vengeful and violent implications of the verse, and has obscured its message that a larger, more eternal and meaningful reality exists beyond the paltry Pulp Fiction world of Marsellus.

Still, the fact that Jules has some awareness of this biblical perspective, however mistaken it may be, helps to provide the framework for what Frankl calls “a confrontation with and reorientation toward” the ultimate meaning of his life. When both Jules and his fellow hit man Vincent are shot at point blank range with a .357 magnum, surprisingly neither is hit. While Vincent shrugs it off as a freak occurrence, Jules sees the incident as a life-transforming miracle.

How the two interpret what happens says a lot about how they understand the world. Vince, a heroin addict, sees no reality beyond the brutal world he inhabits. Jules, who at least has some dim awareness of Ezekiel’s higher, more spiritually ennobling perspective, insists it was an act of God. “Whether what we experienced was an according-to-Hoyle miracle is insignificant.” Jules tells Vincent. “What is significant is I felt God’s touch, God got involved.”

How the two interpret what happens says a lot about how they understand the world. Vince, a heroin addict, sees no reality beyond the brutal world he inhabits. Jules, who at least has some dim awareness of Ezekiel’s higher, more spiritually ennobling perspective, insists it was an act of God. “Whether what we experienced was an according-to-Hoyle miracle is insignificant.” Jules tells Vincent. “What is significant is I felt God’s touch, God got involved.”

As a result of feeling God’s touch, he chooses to turn away from his life of iniquity—to repent, in other words—and decides to walk the earth until God puts him where God wants him to be. Vincent, whose skepticism blinds him to the miraculous implications of what happened, remains in the Pulp Fiction narrative and later meets an unexpected and violent end—the wages of sin being death, after all.

So beyond the drugs, violence, and sex, Pulp Fiction is really something of a morality tale about the redemption of a hit man—and if he can find salvation through an awareness of the divine (however murky it may be), perhaps we can too. As one commentator puts it, Samuel Jackson’s performance “is so perfect that we utterly believe every word he says and take all of his theological philosophy into our consciousness and ponder it ourselves.”

So beyond the drugs, violence, and sex, Pulp Fiction is really something of a morality tale about the redemption of a hit man—and if he can find salvation through an awareness of the divine (however murky it may be), perhaps we can too. As one commentator puts it, Samuel Jackson’s performance “is so perfect that we utterly believe every word he says and take all of his theological philosophy into our consciousness and ponder it ourselves.”

A minister preaching from a pulpit can only hope to have that kind of impact. But what about The Big Lebowski? Could there be such a spiritual purpose underlying this entertaining cinematic mess?

When I first saw the movie, I have to admit that I was a bit puzzled by it. I couldn’t make a lot of sense out of series of random events that serve as the movie’s plot. But there was also something deeply satisfying about The Big Lebowski that I couldn’t quite define.

When I first saw the movie, I have to admit that I was a bit puzzled by it. I couldn’t make a lot of sense out of series of random events that serve as the movie’s plot. But there was also something deeply satisfying about The Big Lebowski that I couldn’t quite define.

Was it the hilarious, f-word laden dialogue between Jeff Bridges and John Goodman, who plays Walter, an edgy Vietnam veteran, private investigator, and bowling partner of the Dude? Was it the absurd situations that unfold around the Dude, like when a trio of nihilists barge into his apartment and toss a live ferret in the tub with him as he’s taking a bath and smoking a joint?

Yes, that’s all entertaining, but there is still something more to The Big Lebowski that’s hard to describe. As Jeff Bridges has said about the movie, “What’s great about (it) is how it says it all without saying anything.” He goes on to reflect: “Maybe that’s one reason people dig the movie and are able to watch it over and over again. It’s like picking up a kaleidoscope. You see something new each time.”

Interestingly, Bridges also sees a Zen-like wisdom underlying the film. For him, The Big Lebowski is, as Zen describes itself, like a finger pointing at the moon, something small and finite shifting our awareness to something much larger and more enduring than itself. That, for me, is the something that I couldn’t exactly put my finger on when I first saw the movie.

Interestingly, Bridges also sees a Zen-like wisdom underlying the film. For him, The Big Lebowski is, as Zen describes itself, like a finger pointing at the moon, something small and finite shifting our awareness to something much larger and more enduring than itself. That, for me, is the something that I couldn’t exactly put my finger on when I first saw the movie.

Where Pulp Fiction presents an essentially dualistic Christian dilemma (do we define ourselves by our godly or satanic selves, our lower or higher impulses?), The Big Lebowski, like Zen, questions whether such an egocentric dilemma even exists. As one author points out, in Zen “it is not enough to raise the ego to a higher synthesis; it is necessary to transcend the ego altogether, that is, to break out of the dualistic matrix which the ego itself embodies.”

In other words, it doesn’t matter whether you allow the satanic narrative of Marsellus to define who you are, or whether you accept the divine perspective of Ezekiel…according to Zen, they’re both equally subjective and ultimately false.

In The Big Lebowski there is no larger, objective narrative, just characters that all bump up against the limitations of each others subjective ego stories. As one character in the movie says, “You have your story, I have mine.” Walter’s story, for example, is forever mired in his combat experience in Vietnam. The Dude, an aging SDS radical from the ‘60s, still smokes pot, loves Credence Clearwater Revival, and frequently says “far out.”

These and other fragmentary stories make up the ever-shifting kaleidoscope of confusion that the Dude tumbles through like the tumbleweed we see drifting around LA in the film’s beginning. Everything in his world is relative. Words have no common meaning. Situations are arbitrary and chaotic. No one’s identity is clear or certain.

As Walter says to another character, everyone in the movie, and everyone in the audience, is like a child who wanders into the middle of a movie with no frame of reference. Any cohesive meaning in the movie—and perhaps even in our own lives—is as elusive as the Dude’s fruitless search for the rug that really tied his room together.

As Walter says to another character, everyone in the movie, and everyone in the audience, is like a child who wanders into the middle of a movie with no frame of reference. Any cohesive meaning in the movie—and perhaps even in our own lives—is as elusive as the Dude’s fruitless search for the rug that really tied his room together.

It would be wrong to say that The Big Lebowski is nihilistic, though. In fact, it portrays nihilism as just another contrived and self-deluding ego story. Jeff Bridges points out that the movie’s message of there being no message is more in line with Zen. According to one source, “the western Judeo-Christian teaching is that of words, concepts, theology and philosophy…(while) the Zen teaching communicates neither ‘the word,’ nor a ‘message,’ but awareness. It is in this sense that Zen teaches nothing.”

This difference between the western and eastern approach is illustrated toward the end of the movie when the Dude and Walter are at a funeral home attempting to dispose of the body of their friend Donnie. On the wall of the funeral director’s office are words from the Psalm that I read before our time of silent meditation: “As for man, his days are as grass; as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth; for the wind passeth over it and it is gone.”

Moving words about our mortality, to be sure, but they seem to have little impact on Walter and the Dude. It isn’t until Walter pours Donnie’s ashes from an empty coffee can along the California coastline (in accordance, Walter says, with what they thought his dying wishes might well have been), that the two have a sudden and direct experience with the wind of mortality the Psalm describes.

Moving words about our mortality, to be sure, but they seem to have little impact on Walter and the Dude. It isn’t until Walter pours Donnie’s ashes from an empty coffee can along the California coastline (in accordance, Walter says, with what they thought his dying wishes might well have been), that the two have a sudden and direct experience with the wind of mortality the Psalm describes.

In this funny and strangely poignant scene, a gust of ocean wind blows Donnie’s ashes back onto Walter and the Dude, which jolts them momentarily out of their subjective selves.

The Dude loses his cool façade and in the script Walter is described as “for the first time (being) genuinely distressed, almost lost” as he apologetically wipes the ashes from the Dude and tries to placate his raging friend. They experience the actual wind described in the Psalm which blows through their dualistic ego selves and for a moment unites them in an embrace of genuine communion.

American Buddhist Joseph Goldstein writes that this form of communion is at the heart of Buddhist teaching. “When there is no self, there is no other,” Goldstein observes. “Duality is created by the idea of self, of I, of ego. When there’s no self, there is a unity, a communion.”

Christian monk and Zen practitioner Thomas Merton said that this egoless communion “does not consist in ‘abiding’ in a secret mystical point in one’s own being, but in abiding nowhere in particular, neither in self nor out of self.” And that’s where the Dude finds himself at the end of The Big Lebowski as he and Walter embrace on that wind-blown California bluff: abiding nowhere in particular with no grand insight into anything he can articulate.

Christian monk and Zen practitioner Thomas Merton said that this egoless communion “does not consist in ‘abiding’ in a secret mystical point in one’s own being, but in abiding nowhere in particular, neither in self nor out of self.” And that’s where the Dude finds himself at the end of The Big Lebowski as he and Walter embrace on that wind-blown California bluff: abiding nowhere in particular with no grand insight into anything he can articulate.

That’s it. But that’s enough. As he says at the end of the movie, “Well, you know, the Dude abides.” The cowboy stranger who narrates the movie finds great comfort in that. “The Dude abides…” he says. “It’s good knowin’ he’s out there—the Dude—takin’ ‘er easy for all us sinners.”

But it’s just a movie, right? I’m reading way too much into something that’s just a piece of entertainment. Perhaps. But a volunteer fireman who survived the 9/11 attacks feels differently.

After witnessing firsthand the horror of that day, watching men and women jump from the burning towers and losing many friends and fellow first-responders, the fireman understandably suffered a debilitating case of post-traumatic stress. One day, as he sat depressed in his living room, he spotted a DVD copy of The Big Lebowski on his shelf and decided to watch it.

“For the first time in six months,” he said, “I smiled and I started laughing.” And he kept laughing. As he watched the movie again and again, something about it brought him out of his depression and back into life. The Dude does indeed abide…and so do we.

“For the first time in six months,” he said, “I smiled and I started laughing.” And he kept laughing. As he watched the movie again and again, something about it brought him out of his depression and back into life. The Dude does indeed abide…and so do we.

The stories we create—whether they’re vulgar or not, whether we tell them from the pulpit or from the movie screen—end up also creating us. And in a world where our path is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men, we need stories that create in us the hope proclaimed by the hit man and the Dude: that miracles can happen and even if they don’t, there’s still hope for all us sinners that we will, like the Dude, find some way to abide.

(Hymn: the UU version of “Abide with Me”)

Hymn Closing Words

(Adapted from the end of The Big Lebowski)

‘The Dude abides’ . . . I don’t know about you, but I take comfort in that. It’s good knowin’ he’s out there, the Dude, takin’ ‘er easy for all us sinners. Well, that about wraps ‘er all up. Things seem’d to have work’d out pretty good fer this service. I hope it’s provided some insight into the way the whole dern human comedy keeps perpetuatin’ itself, down through the generations, westward the wagons, across the sands of time until we . . . ah, look at me, I’m ramblin’ again. Well, I hope you folks enjoyed yerselves. Catch ya later on down the trail.

Beautiful

Beautiful, simply beautiful

Thanks for posting, Dudely!

Also, thanks for the comments, harri3kk.

Abidingly,

The A-D

Brother Dudely, you spoke well. True beauty.

Abidingly

Brother Aleks, a.k.a. Swiss Dude