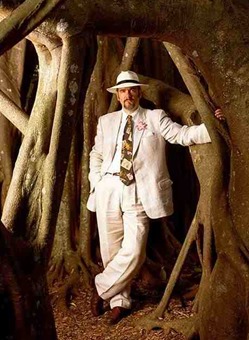

Our friend and contributor to Lebowski 101, Guido Mina di Sospiro is an accomplished writer who, later in life, turned his hand to a new pastime – table tennis. In his recently published book The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, Mina di Sospiro discusses the philosophies inherent in the game, and even how ping pong can relate to various aspects of life. Here’s our interview with him!

Our friend and contributor to Lebowski 101, Guido Mina di Sospiro is an accomplished writer who, later in life, turned his hand to a new pastime – table tennis. In his recently published book The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, Mina di Sospiro discusses the philosophies inherent in the game, and even how ping pong can relate to various aspects of life. Here’s our interview with him!

You’re a big fan of The Big Lebowski and have even contributed an article to our book Lebowski 101 about how the film is influenced by Taoism. Do you feel that Taoism informs the sport of ping pong as well?

Absolutely. And in fact China consistently produces the best players in the world. East Asia, really, remains the place for sublime table tennis: China, Japan and South Korea.

What are the similarities between bowling and ping pong? How do these sports differ from other sports?

What are the similarities between bowling and ping pong? How do these sports differ from other sports?

As somebody who considers The Big Lebowski the greatest film ever made, I’ve asked myself the same question. Bowling would seem to employ the biggest and heaviest ball of all sports, whereas table tennis uses the smallest and lightest. In both advanced bowling and table tennis, however, spin is of the essence. And while I am a poor bowler, unable to produce any spin, when it comes to table tennis, that’s my main weapon. In fact, I would not be interested in table tennis were it not for the amazing amount of spin that can be produced, especially with Chinese rubbers of a certain type. I suppose that’s because I am a philosopher, and I could not resist the allure of non-Euclidean geometry afforded by competitive table tennis. I mean, forget predictable trajectories with moderate curves and speed. In contemporary, competitive table tennis it’s all about the curve, or arc, of the loop, how the ball rotates while in the air, how it dips or kicks or jumps to either side on impact with the table, and then on the opponent’s racket. Much of the game boils down to “reading” the opponent’s spin—and neutralizing it. Some not-so-advanced players have said that playing with me is like playing chess, except at absurd speeds. Coming back to the similarities with bowling, both TT and bowling are widely seen as arcade games, so to speak. Yes, since 1988 table tennis has become an Olympic sport, but most people still consider it a pastime, something to be played in somebody’s basement. Bowling is equally frowned upon. And yet I find that both lend themselves to philosophical extrapolations. In order to participate in tournaments, as both the Dude and I have in the respective sports, it takes a lot of training and concentration, discipline, effort. Last but not least, remember the scene in which the Dude listens in his headphones to bowling sounds—and smiles? When I go to my table tennis club and climb up the stairs that lead to the rooms in which the tables are, and I hear the familiar sound of the little ball bouncing around, a smile dawns on my face. It’s a reflex.

What are the most important life lessons you learned in your quest to master ping pong?

What are the most important life lessons you learned in your quest to master ping pong?

To answer, I’m going to resort to a reader’s review about The Metaphysics of Ping Pong that’s been published on Amazon: ‘Maybe the antidote for the supposed “cultural decay” and “spiritual void” that many of us westerners love to whine about lies in paying close attention to activities that apparently don’t seem to manifest the “gifts of the spirit”. In this brilliant autobiographic essay, Guido Mina di Sospiro shows the reader that initiation, and its inherent intellectual and spiritual discipline, may be more readily available than we think. It might even be lying dormant in our basement, neglected by our prejudices, shrouded by a veil of snobbery that distorts our senses and allows us to be easily impressed by arcane rituals, decorated aprons and other esoteric bling … In this sense, The Metaphysics of Ping-Pong is a lesson about humility, cultural competence and the importance of keeping our mind uncluttered by convention.’ I think that one the Coen Brothers’ many strokes of genius in the film was using bowling as a common ground for the Dude, Walter, Donny and an assortment of eccentrics and weirdoes. Critics, of course, missed the point altogether—but what else is new? We did not. Of course, the lofty would be found in the mundane. The Dude and his friends could have been, say, members of a chess club. In theory, that would have been more suited to philosophical speculation, but in fact it wouldn’t have worked at all. That’s why I have entitled my book The Metaphysics of Ping-Pong: to go from the sublime to the ridiculous; from the lofty to the mundane; from quoting Plato and Lao–Tzu to quoting a proverb.

Speaking of that, I was pleasantly surprised by the tone in your book: now elevated, now folksy.

Speaking of that, I was pleasantly surprised by the tone in your book: now elevated, now folksy.

Well, that’s the idea: the universe has a sense of humor. After all, Jesus, Buddha, Lao-Tzu—all had to take a leak, from time to time. Yes, western philosophy of the discursive type, the one taught at school of an Aristotelian slant, is dreadfully self-serious. But when it comes to the Zen, Tao and Sufi traditions, things change: philosophy is taught through short stories that challenge our assumptions and seem to resemble clever jokes. The western canon still imposes a worldview that has been superseded decades ago, in some cases over a century ago, by academia itself. It’s as if we still lived in the Newtonian mechanistic universe of invariable laws, when it’s all been proven wrong by science itself. Think of non-Euclidean geometry; of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and of quantum mechanics; of the theory of chaos; of ?ukasiewicz’s three-valued logic. The more science advances, the closer it becomes to Taoism and to other ancient esoteric traditions. Yet, here in the West, we are inculcated since kindergarten a materialistic and deterministic nightmare that is nothing more than an intellectual abstraction—and an aberration.

Your ping pong journey introduced you to many colorful characters, all of whom approached ping pong in various ways. Similarly, The Big Lebowski is full of various conflicting attitudes, all of which are appreciated by The Dude. How did you manage to get along so well with such bizarre and often contrary characters? Was there something in ping pong which drew you together?

Your ping pong journey introduced you to many colorful characters, all of whom approached ping pong in various ways. Similarly, The Big Lebowski is full of various conflicting attitudes, all of which are appreciated by The Dude. How did you manage to get along so well with such bizarre and often contrary characters? Was there something in ping pong which drew you together?

Yes, I call it the lingua franca of table tennis, spoken by the multi-ethnic Tribe of the United Colors of Table Tennis. I have often played with opponents who barely spoke English, or none at all. It didn’t seem to matter. We spoke… table tennis. The familiarity achieved almost instantly after a few rallies during warm-up is uncanny. It’s as if we had grown up together, and gone to the same school. In fact, my opponent may be from Madagascar, or from Mongolia, or from the Republic of Tajikistan—and where is that, exactly?

You’ve got quite the multi-cultural background which seems to inform much of your philosophy. In what way has that helped you make sense of the world? The world of ping pong you participated in was also very culturally, nationally and ethnically mixed. Did your broad heritage have something to do with your interest in the game and its players?

You’ve got quite the multi-cultural background which seems to inform much of your philosophy. In what way has that helped you make sense of the world? The world of ping pong you participated in was also very culturally, nationally and ethnically mixed. Did your broad heritage have something to do with your interest in the game and its players?

I don’t think so. When I embarked on my table tennis adventures, I had no idea that it was such a cosmopolitan sport. Also, the fact that the book is set in and around Washington, D.C., must have contributed to the number of foreigners I met and played with. Yes, I myself have a multi-cultural background, but table tennis seems to have expanded on it. For example, one tends to revaluate a whole nation if a player hailing from it happens to be adept. It sounds childish, but so be it. Case in point: my friend and teacher Jaime Álvarez. In his youth, he and his brother Mario happened to be world-class players from the Dominican Republic, of all places. Before meeting Jaime, I used to think of the Dominican Republic as a beautiful Island in the Caribbean with welcoming people and nice beaches. Now I think of it as one of the TT centers in the universe, which to me means a lot more than the sport itself.

What advice would you give to someone who wished to embark on a journey like yours? That is, mastering a sport or art later in life or with difficult odds of succeeding?

What advice would you give to someone who wished to embark on a journey like yours? That is, mastering a sport or art later in life or with difficult odds of succeeding?

The epiphany at the end of The Metaphysics of Ping-Pong is that form is not of the essence, form is the essence. In The Republic Plato writes beautifully about the World of Forms through his famous allegory of the cave. And perfect form, in any sport and indeed in any discipline (think of any performing art), is achieved by dint of repetitions. The East Asians, who remain the best table tennis players in the world, all consider calligraphy the greatest of all arts. And calligraphy of that level entails unlimited patience and practice, and so do martial arts, table tennis, playing a musical instrument, bowling—you get the picture. Repetition, therefore, must not be frowned upon, but cultivated. In fact, repetition is at the very core of alchemy (explaining how, though, is well beyond the scope of this interview). When I was in my teens, I put a lot of effort into learning to play the classical guitar. Thanks to a very good teacher and to my passion, I eventually managed to play—flawlessly—all of Heitor Villa-Lobos’s compositions for the guitar at age seventeen; in retrospect, too much, too soon. All that technique didn’t get me any closer to the World of Forms. In fact, I soon lost interest in the instrument. The mastering of a sport or of an art in life is probably best if achieved during our maturity, a time in which, beyond the technique, we can catch glimpses of an archetypal world. And the more we see of it, the more we want to know. Under normal circumstances, in other words, without the area rug emergency, the Dude, Walter and Donny would be shown practicing their bowling technique tirelessly. Typically, that is frowned upon by society, i.e., people like the other Lebowski. Playing is for children, we are told, not for adults. I have a whole chapter in The Metaphysics of Ping-Pong, entitled Homo Ludens, about this other dogma of western society. The thing that bothers “liberal” thinkers about adults playing is that play of any type is based on absolute laws—its rules—so that that other intellectual abstraction so dear to the western world, relativism, inevitably collapses. In The Big Lebowski the Coen Brothers make such a point very vividly: Walter nearly shoots a fellow bowler because he’s put his foot past the line by a few inches! It’s extreme, but it illustrates how dead serious rules of any game can be. My contention is that if adults spent a lot more time playing, there may be less hostility in the world, and possibly fewer wars.

In the book you point out that metaphysics originally regarded "what underlies everything" but now has come to mean "anything beyond the physical." What do you think this says about the current popularity of "spiritual" movements which often co-opt this term? In ferreting out the metaphysics of ping pong (in the traditional sense of the word) do you think that this approach could or should be applied to other pastimes?

In the book you point out that metaphysics originally regarded "what underlies everything" but now has come to mean "anything beyond the physical." What do you think this says about the current popularity of "spiritual" movements which often co-opt this term? In ferreting out the metaphysics of ping pong (in the traditional sense of the word) do you think that this approach could or should be applied to other pastimes?

The “spiritual” movements that often co-opt the word “metaphysics” don’t really know what it means, and they take it literally for “beyond the physical.” Scholars usually offer a list of what the term meant from its earliest appearance – the writings of Aristotle that came after his writings on physics, in the arrangement made by Andronicus of Rhodes about three centuries after Aristotle’s death – to the differences between “old” and “new” metaphysics, ending with the startling question: Is metaphysics possible? (Indeed, metaphysics was proudly declared dead by western philosophers early on in the last century, particularly by those in the Vienna Circle.) One might have a better answer if they knew what metaphysics is in the first place. Traditionally metaphysics is a branch of philosophy whose objective is to understand the nature of first principles, be they visible or invisible. It concerns itself with being as being and the first causes of things. As noted, a traditional metaphysician is one who tries to discover what underlies everything. And yes, I do think that this approach could be applied to other pastimes, bowling included.

You delineate a fascinating difference between the "metaphysicians" and the "empiricists" in the world of ping pong. Can you briefly summarize the difference between the two? Do you see the same division in our cultural world at large.

You delineate a fascinating difference between the "metaphysicians" and the "empiricists" in the world of ping pong. Can you briefly summarize the difference between the two? Do you see the same division in our cultural world at large.

Briefly, in table tennis the metaphysician strives to achieve — Platonic, whether (s)he realizes it or not — perfect form by adopting contemporary TT’s most metaphysical element: spin, and loads of it. The empiricist, on the other hand, rejects spin because (s)he can’t cope and/or deal with it, doesn’t try to learn its secrets, and buys instead tricky rubbers that either neutralize it (anti-spin), or reverse it and send it back with weird trajectories (long pips). The shortcut to the occasional victory against not-so-advanced-opponents becomes the infinite longcut to the mastering of the art of table tennis: such players shall never learn it, nor shall they ever catch a glimpse, even, of the world of forms. Yes, our cultural world is still in the hands of empiricists. Quickly put, in the West we live in an all-pervasive and compulsory Euclidean/Aristotelian/Cartesian/Newtonian/Darwinian nightmare, which is taught at school and enforced at every turn. Such a worldview is a pernicious abstraction that has nothing to do with real life, but we are made to comply with it. Some, however, will put up a form of civil disobedience, be it by living in a tiny cabin by a pond, by saying “f…k it!” to odious people like the other Lebowski, or by spinning a little ball across a table. This kind of gentle subversion promotes a sense of well-being.

You point out that "embracing chaos is a saner approach" than trying to engineer the outcome of our lives via deterministic efforts. Certainly our hero The Dude lived his life that way. How did you apply it to your ping pong studies? Or even, to your life?

The Dude is a prime example of a sane approach to life, even under duress. He really is transcendental. As for how I apply that in my life, well, I’ve finally understood that making plans is God’s favorite form of comic relief—don’t even try! There seems to be a lot in life that is counterintuitive (for our left side of the brain, that is, which unfortunately has become dominant). For example, when I lived in Miami our neighbor, a kindly old man, one day told me: “If you want it to rain, turn on the sprinklers.” That seems just right.

THE METAPHYSICS OF PING-PONG is available at the following links:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.