[An excerpt from Jorge Guerra’s (a.k.a. Todo Duderado) book “Acidhead and Stories”]

The next day we tripped all day and into much of the night. I’m not sure if it was from exhaustion or paranoia, but at some point in the trip I lost my sense of touch. I pinched myself and felt like I was pinching something dead. I felt on the verge of a bad trip, and I calmly and gently explained to Annie that I was about to freak out.

We found a water-fill station, and I put the back of my neck under the spout. The water revived me. I wanted to stay under the current forever, but some hippies started yelling at me about water conservation so I had to leave.

Annie and I decided to look for the lake, which proved hard under the conditions, and my sense of touch started wandering off again. Eventually we did find it, by stalking some still-dry hippies with towels and swimsuits. I went in the water and came around. Annie didn’t want to miss the music. I told her to go ahead and I’d meet her later that night at Yonder Mountain String Band. I stayed at the lake till sundown. I was still tripping fairly hard when I walked off and got lost in a forest. The forest had secret playgrounds where pixies with pointy ears were dancing with LED hulahoops like career experts.

One pixie with a hulahoop was holding a clipboard and trying to register people to vote. The lights attracted people to register, but they couldn’t get close to the clipboard because she refused to stop dancing.

One pixie with a hulahoop was holding a clipboard and trying to register people to vote. The lights attracted people to register, but they couldn’t get close to the clipboard because she refused to stop dancing.

There were glowing geometric shapes hanging from the trees. I came out of the forest into a bazaar. Throngs of people were going each way in the bazaar. It was loud, and I could hear the music from all the stages mixing above me. Hippies tried to sell me drugs as I walked past them. Golf cart taxis were trying to get through, and the cabbies were yelling. Golf cart ambulances were coming through with passed-out hippies and they were blowing horns and whistles. I felt a need to run away from there, but there was no way. I looked around and found a big tarp tent between two tie-dye freaky ones. Inside there were skinny folding chairs and particleboard tables. A few hippies were sitting on the chairs listening to a man with a round black hat and a big wiry beard with curls for sideburns that reached his jaw. I thought it was Matisyahu. I decided at once to go there and ask if I could take a rest.

It wasn’t Matisyahu. It was a Hassidic rabbi reading the Torah. When I came up he said, “Shabbat Shalom!”

It wasn’t Matisyahu. It was a Hassidic rabbi reading the Torah. When I came up he said, “Shabbat Shalom!”

I told him I loved his set with The Wailers. He laughed and twirled his curly sideburns; then he offered me a chair. He was teaching about the holiday of Purim, the one where Jews dress in costumes and eat and drink.

There was a man called Haman, who was like a biblical Hitler. He was a henchman to the Persian king Xerxes. Xerxes had a harem, and among the women there was a Jewish girl named Esther. When Haman cast the Pur and tried to kill all the Jews in Xerxes’ empire, Esther intervened on behalf of her brother Mordecai. Xerxes was so in love with Esther that he reversed the order and gave leave to all the Jews to kill their persecutors. When this was done, all the Jews celebrated, and that celebration was called Purim.

The rabbi rocked back and forth and played with his beard as he taught. This is what I remember him saying: “After they realized they’d been saved, they became acutely aware that they existed. The mere fact of their existence had to be celebrated, so they got together and did it. Because to exist collectively is to celebrate, and to celebrate is to elevate existence. To celebrate another’s existence is to celebrate your own existence. To celebrate another’s existence is also to toast, and to toast is to drink wine and break bread.

“To hand yourself over to the celebration is also to forgive debts, because he who owes you is your neighbor, and so he would be at your celebration, your block party.

“To hand yourself over to the celebration is also to forgive debts, because he who owes you is your neighbor, and so he would be at your celebration, your block party.

“In this way men redeem themselves through the celebration, and in complete redemption men know God. That’s what Purim is: Whenever men gather for the sake of gathering, it is Purim.”

When a hippie asked him why they dressed up in costumes during Purim he said, “By putting on a costume we’re taking off a costume. We’re making a conscious decision to declare war on any superficiality. And there’s no limit to how far this can be taken in Purim, because if men constantly know themselves superficially they don’t know themselves inside. To know yourself deeply and to know your neighbor is to know God. To not know is to be sick. The stronger the sickness the stronger and even dangerous the antidote must be. So we must wear costumes and drink and eat in excess.”

When they asked him why then did the Jews fast and become solemn during Yum Kippur the rabbi answered, “There’s a solitary pursuit of God and there is a communal pursuit of God, and both are important. We pursue and create God through fasting, meditation, and study, and this is a vertical pursuit of God; and we pursue and create God through good deeds toward people and by celebrating with them, and this is a horizontal pursuit. To discover God in ourselves we must create a cross; that is, an X and Y axis.

“That is to say — ha! — that is to say that we must work hard and play hard; that is, we must ’fight for our right to party!’ as the Beastie Boys would say.”

“That is to say — ha! — that is to say that we must work hard and play hard; that is, we must ’fight for our right to party!’ as the Beastie Boys would say.”

When he said that he showed a lot of white teeth through his beard and as he laughed he rocked back and forth like he did when he read from the Book.

I felt much better after resting in the tent with the rabbi. He gave me and some other hippies food and water. I wished Annie could have met him. I’d never seen a Hassid at a festie. I’d never talked with a man who made spiritual knowledge his life calling. The speech seemed fitting, like from Providence or something. It seemed fitting that I should wander into the tent just when I’d come down enough from my trip to have a coherent conversation, while still high enough to get my mind blown. But then I’m sure all the other hippies felt exactly the same way.

This rabbi, Nebbish, wasn’t like any of the Jews I’d met. He was more essential, but I could see some of that essence in all of them. They’re a people of the herb and of the getty; of the plate like the Italians, and of the jest, and also of the book. Somehow all those inclinations seem to go hand in hand. They’re what attract me to Jews, especially their affinity for the herb. Nearly every Jew I’ve ever met likes to smoke reefer.

I decided to head for Yonder Mountain String Band. I looked for Annie and Jenn, though my search was cut short by the distraction of the music. Finally I decided it was good enough to know they were witnessing it too, somewhere in the crowd. It turned out to be the best show of the festival.

I decided to head for Yonder Mountain String Band. I looked for Annie and Jenn, though my search was cut short by the distraction of the music. Finally I decided it was good enough to know they were witnessing it too, somewhere in the crowd. It turned out to be the best show of the festival.

A kid named Ryan Sollier smoked me out in the crowd, and my trip was rebooted. I had my second big peak of the day when they played Midwest Gospel Radio. It was so much string music I felt like my body was softly breaking off in fractals along with my mind, and I was inhabiting everything, like in the fifth panel of Nature of Mind. Ryan Sollier was in front of me, and that was the painting on the back of his t-shirt. I thought the blueness of it was everywhere.

There’s a reason hippies love bluegrass, aside from the angelic nature of string music. There’s a reason this music lends itself to live play and to festivals more than the recording studio. Bluegrass is hoedown music, so it has to have a crowd. It’s hill music, and hill people are always fiercely independent. Even though Yonder is made up of stoner college kids from the Midwest, they’re still plucking the same strings the Appalachian descendents of poor indentured servants have been plucking these last two centuries.

These hill peoples and their music and moonshine are part of the foundation to the counterculture that stands now, which is based on the type of independence that would rather be poor if it means being free. This poverty of the earth is so tied into that independence that it’s synonymous with it, so that to be dirt poor is to be free. And bluegrass is the artistic expression born out of that dirt, and it comes from the dirt in the same way that our cannabis and our mushrooms come from the dirt.

These hill peoples and their music and moonshine are part of the foundation to the counterculture that stands now, which is based on the type of independence that would rather be poor if it means being free. This poverty of the earth is so tied into that independence that it’s synonymous with it, so that to be dirt poor is to be free. And bluegrass is the artistic expression born out of that dirt, and it comes from the dirt in the same way that our cannabis and our mushrooms come from the dirt.

This was my Shroom revelation during Midwest Gospel Radio, and till now and maybe forever I’ve thought of it as one of the most perfect pieces of music that exist. Though of course, stoned aesthetic impressions have a tendency to spill over into your sobriety.

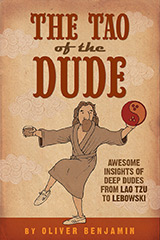

Dig Todo Duderado’s style? Acidhead and Stories can be purchased at Amazon.com

Far fucking out, man!

I aint never seen no rabbi at a damned “festie”, so the fella says, but I have seen Hare Krishna monks feeding lots of people at various hippy fests. Those are good prasadam, Walter!

I’ll have to check out your book, El Duderado

Thanks, Monk. If you wanna check out the book and give me notes, the website is http://www.authorhouse.com

Catch you later on down the trail