"Secret shit": the uncertainty principle, lying, deviation, and the movie creativity of the Coen Brothers.

By David Lavery

(Originally published in Post Script 27.2 (2008): 141-153)

I. THE RUMPUS

Billy Bob Thornton: People ask me a lot of times in interviews, 'What have you learned as a director when you've worked with other directors,' and they most often ask me about you guys.... Ethan Coen: Well, there isn't anything, right? Remember we were kidding about that.... Joel Coen: I remember when we were shooting you were about to work with Barry Levinson [on Bandits (2001)], and Ethan was always admonishing you not to tell Barry any of our secret shit.... Billy Bob Thornton: Then I actually showed up on the set with this bag and told the crew that I had the Coen brothers' secret shit in it.

On the DVD of The Man Who Wasn’t There, Joel and Ethan Coen’s ninth film, Billy Bob Thornton (who plays Ed Crane, the film’s zero-charisma lead), engages in the preceding exchange with the filmmakers. Apparently, the Coens’ "secret shit’–with which, we presume, they have painted, in Freudian anal-stage fashion, their auteur signatures all over their twelve films (I mean this as a compliment)–is so secret, so idiolectic, so arcane that many critics find their movies as empty as Billy Bob’s bag. Even one of their admirers (he too means it as a compliment) has characterized their work as "intentionally bogus and daft and cool" (Halari 30).

On the DVD of The Man Who Wasn’t There, Joel and Ethan Coen’s ninth film, Billy Bob Thornton (who plays Ed Crane, the film’s zero-charisma lead), engages in the preceding exchange with the filmmakers. Apparently, the Coens’ "secret shit’–with which, we presume, they have painted, in Freudian anal-stage fashion, their auteur signatures all over their twelve films (I mean this as a compliment)–is so secret, so idiolectic, so arcane that many critics find their movies as empty as Billy Bob’s bag. Even one of their admirers (he too means it as a compliment) has characterized their work as "intentionally bogus and daft and cool" (Halari 30).

Few major contemporary filmmakers have been recipients of such wildly contrary vituperation and praise. (1) For every David Thomson, who finds Raising Arizona "close to unwatchable: unfunny, technologically impelled, showy, and not just empty, but condescending" (140), we find a Richard T. Jameson, who professes his love for Miller’s Crossing’s

fortitude to lay all its cards on the table in the first sequence and then demonstrate, with each succeeding scene, that there is still story to happen, there is still life and mystery in character, there is reason to sit patient and fascinated before a movie that loves and honors the rules of a game scarcely anyone else in Hollywood remembers anymore, let alone tries to play. (22-23) (2)

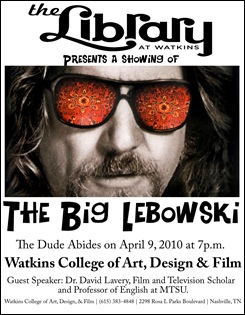

If Jonathan Rosenbaum, in a review of Barton Fink, derides the Coens’ "soulless," "crass consciousness" (248), R. Barton Palmer praises their "magical realism that does not demand verisimilitude or logical closure, but has the virtue … of permitting more stylization, more moments of pure cinema" (108). If Devin McKinney denounces Fargo as "a fatuous piece of nonsense, a tall cool drink of witless condescension," "a betrayal–of themselves, of their audience, of a human milieu" (31-32), Geoffrey O’Brien finds it "the Coens’ most successful film … because of the way Frances McDormand’s character asserted, for once, an independent life" (35). Stuart Klawans finds The Big Lebowski "an empty frame" (36), but Roger Ebert, as if in direct reply, counters that while "Some may complain The Big Lebowski rushes in all directions and never ends up anywhere," that "isn’t the film’s flaw, but its style." (3) For every Owen Gleiberman, who introduced O Brother, Where Art Thou? as the Coens’ "latest misanthropic flimflam" (49), a Charles Taylor, who–contrary to his usual opinion of the Coens–finds it a work of "dogpatch rapture," a case of the brothers "really cooking."

In the continuing rumpus over the Coens, while their extollers find them eccentric geniuses, their detractors characterize them as little more than cinematic grifters. Such radical disparity of opinion almost invites the creation of a critical uncertainty principle. So: what’s in the bag? Just what exactly is the Coens’ "secret shit"?

II. THE UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

They got this guy, in Germany. Fritz something-or-other. Or is it? Maybe it's Werner. Anyway, he's got this theory, you wanna test something, you know, scientifically--how the planets go round the sun, what sunspots are made of, why the water comes out of the tap--well, you gotta look at it. But sometimes, you look at it, your looking 'changes' it. Ya can't know the reality of what happened, or what 'would've' happened if you hadden a stuck in your goddamn schnozz. So there 'is' no 'what happened.' Not in any sense that we can grasp with our puny minds. Because our minds ... our minds get in the way. Looking at something changes it. They call it the 'Uncertainty Principle.' Sure, it sounds screwy, but even Einstein says the guy's on to something. --Freddy Riedenschneider, The Man Who Wasn't There (66-67)

In 1927, Werner (or is it Fritz?) Heisenberg proved definitively that, since it is impossible to accurately measure paired variables at the subatomic level–the act of measuring itself apparently altering the measurable–it appears necessary to conclude that the presence of an observer may actually change the reality of the observed. Under the sway of Heisenbergian indeterminacy, to cite its perhaps most celebrated implication, even the nature of light (the only constant, the [c.sup.2] of e=m[c.sup.2]) became indecipherable. Is it a wave? A particle? Only the observer knew for sure in a new, participatory universe.

In 1935, German quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger proposed a thought experiment intended as a reductio ad absurdum corrective to the Uncertainty Principle. Schrodinger apparently found Heisenberg’s thesis intolerable and therefore imagined his infamous feline to demonstrate his doubts. A character in Greg Bear’s "Schrodinger’s Plague," a science fiction story in which a mad scientist uses the famous paradox to unleash a potentially species-destroying designer virus, offers the following account of Schrodinger’s proceedings:

Schrodinger proposed linking quantum events to macrocosmic events. He suggested putting a cat in an enclosed box, and also a device which would detect the decay of a single radioactive nucleus. Let's say the nucleus has a fifty-fifty chance of decaying in an arbitrary length of time. If it does decay, it triggers the device, which drops a hammer on a vial of cyanide, releasing the gas into the box and killing the cat. The scientist conducting this experiment has no way of knowing whether the nucleus decayed or not without opening the box. Since the final state of the nucleus is not determined without first making a measurement, and the measurement in this case is the opening of the box to discover whether the cat is dead, Schrodinger suggested that the cat would find itself in an undetermined state, neither alive nor dead, but somewhere in between. Its fate is uncertain until a qualified observer opens the box. (478-79)

Now, assuming that you, having sat down to read an essay on the Coen brothers only to be ambushed by an amateurish discussion of quantum physics, are still with me, you’re perhaps wondering–and you have every right–what all this has to do with the Coens. The transition from the world of subatomic particles back to that of the brothers’ movies, though, will not be as difficult as you might think. For Heisenberg himself does something of a Coen cameo, as does Schrodinger’s cat–sort of.

In The Man Who Wasn’t There, fast-talking lawyer Freddy Riedenschneider explains his methodology to Crane and his wife Doris by way of the quintessentially Coenesque speech quoted as an epigraph to this section. Folksy, funny, erudite–just the sort of intellectualizing we might expect from a screenwriter who wrote his Princeton honors thesis on Wittgenstein’s later philosophy (4)–Riedenschnieder’s harangue both enthralls and distances the viewer. Freddy, whom the Coens themselves make fun of on the DVD commentary track, is, we realize, an unreliable narrator, but so are the Coens themselves (see below). He may be full of shit, but is it not secret Coen shit? Is not what he says really a metacommentary on film reception, a rebuke to those often blind critics, unable to take back their own projections from the on-screen Coen projection–those who have stuck their own goddamn schnozzes in the Coens’ shit, whose minds have got in the way of what Robert Warshow called the "immediate experience" of the movies themselves? Down the flaming hallway of the Hotel Earle we can hear "Madman" Mundt, prefiguring Freddy’s spiel, raving, "I’LL SHOW YOU THE LIFE OF THE MIND!" And what of Schrodinger’s cat?

In Barton Fink, traveling salesman/serial killer Charlie Meadows/"Madman" Mundt gives his neighbor in the Hotel Earle, the film’s pretentious, creatively constipated, eponymous "hero," a box for safekeeping. Though the box does not contain a perhaps living/perhaps dead cat, it may or may not contain the head–decapitation being a Mundt signature–of Audrey Taylor, whom Barton may or may not have murdered (Meadows/Mundt, we do know, befriends Barton by disposing of the body). In the film’s final scene, having overcome his writer’s block and completed the assigned Wallace Beery picture only to have it rejected by studio boss Jack Lipnik, Barton walks the beach beside the Pacific, still carrying his parcel. He meets a beautiful woman–the same enthralling figure depicted on the postcard over his desk at the Earle–and they talk:

Beauty: What’s in the box?

Barton: I don’t know.

Beauty: Isn’t it yours?

Barton: I … I don’t know…. (520-21)

As the movie ends, none of our questions about Barton’s guilt or his fate are answered, as Jameson explains in a largely negative review of the film:

Has Barton written 'the best thing I've

ever done,' or merely reduced his

own brief (implicitly dubious) legend

to hack formula, and unsalable formula

at that? The Coens rather fudge

that one, but at the end of the movie

Barton has the box Charlie gave him,

and it may have become his. He's

found the beach and the girl. "Are

you in pictures?" he asks. Is he? We

don't know whether he should look

in the box. We don't know whether,

if he does or doesn't, he could tell us

stories. ("What's in the Box?" 32)

Barton Fink–a film about writer’s block, itself a product of writer’s block, "burped out" (Bergan 131) while the Coens struggled with the screenplay of Miller’s Crossing (whose main character, Tom Reagan, lives at The Barton Arms)–leaves its protagonist as boxed in and indeterminate as Schrodinger’s cat. But the Coens themselves would not be boxed in. They would stick their own goddamn schnozzes into other narratives, would tell more stories, contrive more lies.

III. CINE-MENDACITY

Someone who knows too much finds it hard not to lie. --Wittgenstein, Culture and Value (64e)

Revealingly, the films of the late Federico Fellini, another notorious movie liar, have provoked critical antagonism similar to that directed at the Coens. Fellini, who began his career as one of the founding members of the neo-realist movement devoted to capturing on film, simply and with minimal artifice, quotidian postwar Italy, would declare in a 1966 Playboy interview the need for a "cine-mendacity" to replace "cinema-verite" because "a lie is always more interesting than the truth" (Pepper 58). inheritors of Fellini’s predilection for the forged, (5) the Coens are inspired confidence men (I mean this as a compliment). (6)

An essential ingredient in their secret shit, Coen lies have ranged from the obvious to the subtle and intricate. Their creation, in the best Allen Smithee tradition, of a fictional editor for their films, the Brit Roderick Jaynes (of "Hayward’s Heath, Surrey"), for whom they posited an entire professional career and a cantankerous personality, was exposed only after his nomination for all Oscar for Fargo. (He would later make a comeback, however, writing the introduction to the first volume of Coen screenplays in 2001). The Coens’ claim in their introduction to the published screenplay of The Big Lebowski that it won "the 1998 Bar Kochba Award, honouring achievements in the arts that defy racial and religious stereotyping and promote appreciation for the multiplicity of man" (vi) probably fooled no one. (7) Nor are we likely to be deceived when Ethan Coen tells Terry Gross on Fresh Air that he and Frances McDormand were surprised that her Marge Gunderson was a favorite with audiences–"I thought she was the bad guy," he explains with seeming sincerity; or when he and his brother told all interested parties that they had never read Homer’s The Odyssey (on which O Brother, Where Art Thou? is loosely based).

Their mendacity is not just movie-based. In The Drunken Driver Has the Right of Way, a collection of his often witty, often profane poetry, (8) Ethan Coen offers the following "ABOUT THE AUTHOR" gloss:

Ethan Coen lives outside of Marfa, Texas, on the ranch he won arm wrestling Lady Bird Johnson in a cantina in Ensenada in 1962 (the ensuing love story was celebrated in his memoir Don't Tell Lyndon). He is an expert on the poetry of Walter Savage Landor and many other subjects which he travels the world to lecture upon, unsolicited. Coen is Poet-in-Residence at the University of Big Bend and hosted its "Fire in the John" poetry readings until they changed the open bar policy. Under the pen name G. Willard Shunt, Coen is the author of the Moe Grabinsky mystery stories, detailing the adventures of the wily toll-taker/sleuth. In his spare time he is shot from cannons.

Coen was, of course, only five years old in 1962 and probably could not have been victorious in a contest (or an affair) with our 36th First Lady; the University of Big Bend has not turned out a single graduate; there are no Moe Grabinsky detective fictions. But there was a Walter Savage Landor, (9) and it is revealing in itself that Ethan Coen knew that. Both Coens are much more knowledgeable than they want us to believe.

Famous for their send-ups of film genres, the Coens parody other forms as well with a panache that belies their media personas as unassuming, sometimes anti-intellectual kids in a candy store. In the delightful introduction they co-wrote for the screenplay of The Big Lebowski, for instance, they offer an excerpt from a supposed scholarly assessment of the film entitled But Is It Funny? Its purported author, the British critic Sir Anthony Forte-Bowell–"editor of Cinema/Not Cinema, a journal of movie semiotics’–begins with a convoluted analysis of Three Stooges slapstick that, since Perry and Walker have not seen fit to include it here, I quote in its entirety:

Humor may ... derive from the distribution of pain among characters whose buffoonery precludes the viewer's, reader's or listener's identification. To cite a familiar example, Moe raises two fingers in a horizontal V-shape and impels them toward the eye-socket of Curly, who interposes his upraised hand and catches the V at its apex, thereby inhibiting the fingers from achieving their end. After expressing his satisfaction through the repealed utterance of a laugh-syllable commonly rendered 'nyuk', the attention of Curly is diverted by the right hand of Moe as it flutters up to and above eye-level while the audience, though presumably not Curly, hears a high-pitched tweeting sound. While thus distracting Curly with one hand, Moe strikes him sharply in the abdomen with the other, at which the audience, though presumably not Curly, hears a strike upon a tympanum. The final 'nyuk' of Curly is thus interrupted so that he may retrieve his forcibly ejected breath, and this new breath's more gradual expulsion is so operated upon by his larynx as to form the sound commonly rendered 'ooo'. When Curly meanwhile drops the hand formerly used to parry the assault upon his eyes in order to massage his insulted midriff, Moe avails himself of the opportunity to renew his digital attack upon the unprotected eyes, and succeeds in poking him, upon which success the audience, though presumably not Curly, hears a sound commonly associated with the release of a bent-back spring and usually rendered either 'doing' or 'ba-doing' (which sound, curiously, bears no relation to the sound the eyeballs actually give out upon being forcibly compressed). Moe will in some cases, if sufficiently angered either by Curly's smugness or by some previous evasion of a punishment deemed appropriate by Moe, so far press his advantages as to quickly and repeatedly slap both of Curly's cheeks, alternately forehand and backhand, while the audience and perhaps, in this instance Curly himself (the convention here being ambiguous) hears the slapping sound amplified to an unnatural degree. The pulling of Larry's hair will not be considered here. I will pause to note, however, the whimsy implicit in the very name given Curly either in wry acknowledgement or in absurd refusal to acknowledge what is striking about his physical appearance, videlicet his want of hair, et ergo afortiori his want of curly hair. Analysis reveals no comparable whimsy at work in the assignment of names to Larry and Moe, and an historian might here note that Lawrence and Morris were the given names of the actors by whom they were respectively depicted. All agree that these operations, or more to the point, their depictions, are 'funny'. What is more obscure and what even a frame-by-frame analysis of the films fails to reveal is wherein the nature of the humour resides. A similar difficulty attends analysis of the film under consideration. The Big Lebowski harks back to films of the early 1970s that deal with certain issues attendant to a presumed Generation Gap. In them, a youth who wears bell-bottomed trousers, beads, a shirt with a printed pattern and octagonal glasses, frequently tinted, is bedeviled by an older man wearing straight-bottomed trousers, a solid shirt, a tie with a printed pattern and curviform glasses, untinted, who 'just doesn't understand'. The more supple and intuitive intelligence of the youth is contrasted with the more linear and unimaginative intelligence of the older man, and in the end prevails over it, with the older man frequently arriving at grudging appreciation of the youth's superior values. If the movie is of the subgenre wherein the older man will not concede the youth's superiority, then the older man shall be revealed to be a fossilized if not corrupt representative of a doomed order. The Big Lebowski appears to be some sort of 'spoof' upon this genre. (vi-viii)

At the end of this pitch-perfect parody of academic obscurity, pomposity, and pretension, Forte-Bowell admits that

repeated viewings of [The Big Lebowski] have failed to clarify for me the genre-relevance of the themes of bowling, physical handicap, castration and the Jewish Sabbath. But perhaps we should not dismiss the possibility that they are simply authorial mistakes. Certainly the script could not be held up as a model of artistic coherence. (viii) (10)

In the introduction to Collected Screenplays I, the Coens even lampoon their own screenwriting–which, by all reports, is so polished, overdetermined, and letter-perfect that the decidedly anal pair will permit almost no deviation during shooting–by ventriloquizing the reborn Roderick Jaynes, who reluctantly agreed to introduce the volume. One of Jaynes’ first principles as an editor, we learn, is that he never be required to read the script of the film he is about to cut. "It is the organization of moving images," he insists, "that is the very art of cinema, and true authorship resides in the hand that wields not the pen, but the razor" (viii). (Conveniently, we are told, Jaynes agreed to write the introduction only after the Coens had agreed not to read it prior to publication.) Not surprisingly, Jaynes finds the screenplays for Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, and Barton Fink all disappointing. "Whatever else you say about the Coens," Kenneth Turan has admitted, "they do have a knack for anticipating criticism." (11)

We cannot always be certain, though, that we are not being had. When Joel Coen comments on the DVD of The Man Who Wasn’t There that he often responds to critics’ questions about their cinematic influences by citing significant auteurs and films (because that’s what they want to hear), we are more than ready to believe him, but when he then insists that he and his brother are as influenced by and indebted to less-appreciated genres like the "high school hygiene" film, we are not completely certain that we are not being put on. (12) In "The Making of The Big Lebowski," available on the DVD of the 1998 film, the Coens recall on camera, but without once making eye-contact with the lens, how a woman from Floor Covering Weekly had sought and been granted an interview concerning their new film. Since, in the opening scene of Lebowski, a thug urinates on a carpet in The Dude’s apartment, thereby setting in motion the film’s Chandleresque plot, we find it mostly credible. Details of the interview follow: the FCW representative, we are told, was the only interviewer they have ever encountered who couldn’t wait to get away from the usually reticent pair; the Coens offered to be photographed for the cover of the magazine; mysteriously, the interview never appeared. Suspicious, they claim, that the interviewer might actually have been a previously snubbed critic, and dubious of the existence of a weekly magazine dedicated to flooring, they confess that they came to wonder if the whole affair might have been a hoax. Floor Covering Weekly, however, does exist (see http://www.floor coveringweekly.com/), and it seems entirely likely that the actual flimflam, in whole or in part, might have been the handiwork of the Coens themselves.

IV. STARTLEMENTS

Why make one movie when you can make twelve at the same time? [The Coens'] restless inventiveness revels in narration but chafes at the restrictions and inevitabilities of linear plotting; superb storytellers, they often seem to tell a story to death, as if to denaonstrate that it really wasn't about anything at all. --Geoffrey O'Brien, "O Brothers, Where Art Thou?" (35)

Storytelling, as J. Hillis Miller showed long ago, early in the Age of Deconstruction, tends by, its very’ nature to kink, to succumb to the basic narratological tendency to "trouble or even to confound … straightforward linearity: returnings, knottings, recrossings, crinklings to and fro, suspensions, interruptions, fictionalizings" (68). (13) Lying, especially the cine-mendacity the Coens practice, complicates our understanding of their auteurhood, and, again and again and again, the Coens’ movies kink. Laced–I’m not sure whether I want to create a shoe-tying metaphor or to evoke tampering with a concoction–with dialogue, images, repetitions, moments which we might call, in keeping with the inspiration of Freddy Riedenschneider, "indeterminacies," or, to use the term preferred by O Brother’s Tiresian old man, "startlements," Coen narratology forbids the straight and narrow. In so-called real life, the proven lies of a speaker (say a politician) may lead me to doubt the efficacy’ of anything and everything he or she might say. But the lies of the artist are of a different nature, as the great Jean Cocteau recognized when he insisted that "I am a lie who always speaks the truth." "Startlements" are movie knots, conundrums, lies that speak the truth of the impossibility of narrative and its obsessive need to carry on.

A brief guided tour of Coen startlements might stop, though not always willingly, at a number of locales:

* the Escheresque (see Drawing Hands, 1948) moment in Blood Simple in which sleazy P. I. Loren Visser has to punch through an apartment wall to remove the knife with which Abbv has nailed his hand to a windowsill

* the headache-inducing exchange in Raising Arizona between H. I. and the parole board discussing his honesty:

Chairman: You’re not just tellin’ us what we wanna hear?

H. I.: No Sir, no way. Second Man: ‘Cause we just wanna hear the truth.

H. I.: Well then I guess I am tellin’ you what you wanna hear.

Chairman: Boy, didn’t we just tell you not to do that?

H. I.: Yessir.

Chairman: Okay then. (124)

* the equally paradoxical, race-bending exchange from O Brother, when Everett, Pete, Delmar, and Chris try to convince a blind radio station owner to record their music:

Everett: Well sir, my name is Jordan Rivers and these here are the Soggy Bottom Boys outta Cottonelia, Mississippi–Songs of Salvation to Salve the Soul. We hear you pay good money to sing into a can.

Man: Well that all depends. You boys do Negro songs?

Everett: Sir, we are Negroes. All except our a-cump- uh, company-accompl- uh- uh, the fella that plays the gui-tar.

Man: Well, I don’t record Negro songs. I’m lookin’ for ol’-timey material. Why, people just can’t get enough of it since we started broadcastin’ the ‘Pappy O’Daniel Flour Hour,’ so thanks for stoppin’ by, but–

Everett: Sir, the Soggy Bottom Boys been steeped in ol’-timey material. Heck, you’re silly with it, aintcha boys?

Pete: That’s right! Delmar: That’s right! We ain’t really Negroes!

Pete: All except fer our a-cump-uh-nust! (28-29)

* all those moments of mistaken identity/ identity exchange: Mink’s corpse being mistaken for Bernie’s, and Tom’s masquerade as Johnny Caspar’s new advisor in Miller’s Crossing; "Madman" Mundt, serial killer, passing himself off as Charlie Meadows, insurance salesman, in Barton Fink; Jeff Lebowski being mistaken for The Big Lebowski; escaped convicts pretending to be the Soggy Bottom Boys; Doris Crane imprisoned for the murder her husband commits and Ed Crane executed for murdering Big Dave Brewster’s victim

* the many Coen repetitions, already catalogued by Horowitz and Robertson: howling fat men, acts of extreme violence, "blustery titans," peculiar haircuts, doppelgangers, hats, the Hudsucker Corporation, vomiting, the head vs. heart theme …

* those astonishing tracking shots: of a beer sliding along a bar in Blood Simple; down a road, across a yard, over a fountain, up a ladder, and into Florence Arizona’s mouth in Raising Arizona; literally down the drain in Barton Fink; of plummeting characters Waring Hudsucker (forty-four floors–forty-five, counting the mezzanine) in The Hudsucker Proxy and The Dude, while attached to a bowling ball, in The Big Lebowski

* all those endlessly moving/rolling objects: the Hula Hoop with the mind of its own and the elaborate pneumatic tubes in Hudsucker, the tumbling tumbleweed in The Big Lebowski, the hubcap from Ed Crane’s car in The Man Who Wasn’t There

* Hudsucker’s impossibly/incredibly thick appointment book, complex mailroom, huge office of Sidney J. Mussberger, immense clock

* The Big Lebowski’s shelf of infinite bowling shoes (tended by Saddam Hussein) and endless Busby Berkeleyian steps

* the barber pole as Mobius strip in The Man Who Wasn’t There

* Norville Barnes’s paradoxical mangling of a cliche in Hudsucker: "Genius they say, genius is 99% perspiration, and in my case it’s at least twice that" (36)

* the preposterous prophecy of the Old Man in O Brother–which, of course, comes true:

You seek a great fortune, you three who are now in chains. And you will find a fortune--though it will not be the fortune you seek. But first, first you must travel a long and difficult road--a road fraught with peril, uh-huh, and pregnant with adventure. You shall see things wonderful to tell. You shall see a cow on the roof of a cottonhouse, uh-huh, and oh, so many startlements. I cannot say how long this road shall be. But fear not the obstacles in your path, for Fate has vouchsafed your reward. And though the road may wind, and yea, your hearts grow weary, still shall ye foller the way, even unto your salvation. (8-9)

* Ed Crane’s account of Freddy Reidenschneider’s Clarence Darrow-meets-the-Uncertainty-Principle summation to the jury in his trial in The Man Who Wasn’t There: "He said I ‘was’ Modern Man, and if they voted to convict me, well, they’d be practically cinching the noose around their own necks. He told them to look not at the facts but at the meaning of the facts, and then he said the facts ‘had’ no meaning" (100-01).

In The Man Who Wasn’t There, in a seemingly insignificant shot, we find Ed Crane sitting in the barbershop reading Life Magazine. A story called "Drycleaning: The Wave of the Future" attracts his attention first. Then he turns the page to find a story on the contemporaneous UFO incident at Roswell, New Mexico. For just a moment we glimpse the text in a close-up that enables us (if we freeze-frame the DVD) to read it: "Imponderable absolutes provide a foundation for examination of forays into these realms." Since this is not the original text of the Life article, since, in fact, no such article ever appeared in the magazine, since the Coens have carefully planted it there–what exactly are we to make of the visual presence of such secret shit in the film? How many similar startlements are there, like the Easter eggs in a video game, hidden in the Coens’ films?

V. DEVIANTS

Writing in Film Quarterly, in the largely negative review of Fargo quoted above, McKinney makes such discerning observations about the Coens that it would no doubt help all future adjudication of their work if critics could simply agree to stipulate their validity. The Coens, he insists, walk "a tightrope of their own devising, flirting with the nihilism and ex-cathedra contempt for the poor materials of reality that are the marks of the gifted undergraduate," but the flirtation does not lead to consummation. For their deliverance "from hipsterism," McKinney shows, lies in a variety of factors, often completely ignored by their harshest critics: "a sense of irony that is not merely ironic, a consistent faith in the power of controlled craft to open up holes of chaos in content," a "study of the quirk so monastic and intent it yields ambiguities not retrievable by looser methods," and "an artistic personality which, in opposition to many of their vaunted peers in the film school generation, is less a commercial trademark, a promise of the familiar, than an organizing impulse in the movies themselves" (31). (14)

Though well aware of the common characterization of the Coens "as pastiche artists, as mavens of the literary swipe and the cinematic in-joke," McKinney refuses to accept the accuracy of such pigeonholing. "Certainly the comic contemplation of genre tropes is a player in their game," he writes, "but they have used the in-joke (or, in polite society, intertextuality) not as a self-justifying end but as a springboard to touch depths mostly unplumbed by the purveyors of either pulp fiction or Pulp Fiction" (31; italics mine). Certainly Coen cinematic plumbing does not ignore the plumbing–the dripping pipe that ends Blood Simple, the drain down which Barton Fink’s career departs, the toilet into which The Dude’s head is plunged. There is a method to Coen madness, McKinney would have us believe.

Howard E. Gruber’s exhaustive study of historically significant creative individuals has revealed that every noteworthy life’s work has at its core a "deviation amplifying system’–a proclivity for making new, a self-perpetuating desire to be "never at rest," to reject the homeostatic (176; italics mine). Now, at the end of the first decade of a new century, with twelve films in the can and four more in the works, the now middle-aged Coens, are multiple-Oscar winning filmmakers (for No Country for Old Men [2007]) and will need to dip into that bag of tricks again if they are to retain their status as independent film auteurs. Still bad boys, deviants, their own creative lives as filmmakers are their secret shit.

Works Cited

Barton Fink. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Twentieth Century Fox, 1991.

Bear, Greg. "Schrodiner’s Plague." The Norton Book or Science Fiction. Ed. Ursula K. LeGuin and Brian Attebery. New York: Norton, 1993. 477-84.

Bergan, Ronald. The Coen Brothers. London: Phoenix, 2000.

The Big Lebowski. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. 1997. DVD. Polygram USA Video, 1998.

Blood Simple. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Circle Releasing Corporation, 1984.

Coen, Ethan. The Drunken Driver Has the Right of Way: Poems. New York: Crown, 2001.

–and Joel Coen. The Big Lebowski. London: Faber & Faber, 1998.

–. Collected Screenplays I: Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink. London: Faber & Faber, 2001.

–. The Man Who Wasn’t There. London: Faber & Faber, 2001.

–, and Sam Raimi. The Hudsucker Proxy. London: Faber & Faber, 1994.

Ebert, Roger. Rev. of The Big Lebowski. Chicago Sun-Times 6 March 1998. 12 Feb. 2007 <http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/ apps/pbcs.dll/article? AID=/19980306/ REVIEWS/803060 301/1023>.

–. Rev. of The Hudsucker Proxy. Chicago Sun-Times 25 Mar. 1994. 12 Feb. 2007. <http: //rogerebert.suntimes.com/ apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19940 325/REVIEWS/403250301/1023>.

Fargo. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Gramercy Pictures, 1996.

Gleiberman, Owen. "Coen Toss: In O Brother, Where Art Thou? Joel and Ethan Coen Go Dud Simple." Review of O Brother, Where Art Thou? Entertainment Weekly 5 Jan. 2001: 49.

Gross, Terry. Interview with Ethan Coen. Fresh Air. WHYY Public Radio. Wilmington, DE. 22 Dec. 2000.

Gruber, Howard E. "From Epistemic Subject to Unique Creative Person at Work." Archives de Psychologie 54 (1985): 167-85.

Hajari, Nisid. "Beavis and Egghead." Rev. of Barton Fink. Entertainment Weekly 1 Apr. 1994: 30.

Horowitz, Mark. "Coen Brothers A-Z: The Big Two-Headed Picture." Film Comment Sept.-Oct. 1991: 27-28, 30-31.

The Hudsucker Proxy. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Warner Brothers, 1994.

Intolerable Cruelty. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Robert Ramsey, Matthew Stone, Joel Coen, and Ethan Coen. Universal, 2003.

Jameson, Richard T. "Miller’s Crossing." They Went Thataway: Redefining Film Genres. Ed. Jameson. San Francisco: Mercury House, 1994: 19-23.

–. "What’s in the Box?" Film Comment Sept.-Oct. 1991: 26, 32.

Klawans, Stuart. "The Big Lebowski." Rev. of The Big Lebowski. The Nation 30 March 1998: 35-36.

The Ladykillers. Dir. Ethan and Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan and Joel Coen. Wr. William Rose, Joel Coen, and Ethan Coen. Buena Vista, 2004.

Lavery, David. "’Coming Heavy’: The Significance of The Sopranos." This Thing of Ours: Investigating The Sopranos." New York: Columbia UP, 2002. xi-xviii.

–. "Major Man: Fellini as an Autobiographer." Post Script 6.2 (1987): 14-28.

–. "O Lucky Man! and the Movie as Koan." Literature/Film Quarterly 8 (1980): 35-40.

The Man Who Wasn’t There. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. USA Films, 2001.

McKinney, Devin. "Fargo." Rev. of Fargo, dir. Joel Coen. Film Quarterly 50.1 (Autumn 1996): 31-34.

Miller, J. Hillis. "Ariadne’s Thread." Critical Inquiry 3 (1976): 57-77.

Miller’s Crossing. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Twentieth Century Fox, 1990.

O’Brien, Geoffrey. "O Brothers, Where Art Thou?" Rev. of The Man Who Wasn’t There. ArtForum International 40.2 (Oct. 2001): 35.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Buena Vista Pictures, 2000.

Palmer, R. Barton. "Joel Coen." The St. James Film Directors Encyclopedia. Ed. Andrew Sarris. Detroit: Visible Ink P, 1997: 106-09.

Pepper, Curtis. "The Playboy Interview: Federico Fellini." Playboy Feb. 1966: 55-66.

Raising Arizona. Dir. Joel Coen. Prod. Ethan Coen. Wr. Joel and Ethan Coen. Twentieth Century Fox, 1987.

Robertson, William P. "Joel and Ethan’s Does and Don’ts." American Film Aug. 1991: 33.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. Berkeley: U California P, 1995.

Taylor, Charles. Rev. of O Brother, Where Art Thou?. Salon 22 Mar. 2000. 12 Feb. 2007. <http: //archive.salon.com/ent/movies/review/2000/12/22/o_brother /index.html?CP=IMD&DN=110>.

Thomson, David. A Biographical Dictionary of Film. 3rd ed. New York: Knopf, 1994.

Turan, Kenneth. "The Big Lebowski: Nutcase Noir and Geezer Noir." Rev. of The Big Lebowksi. Los Angeles Times 6 Mar. 1998. 12 Feb. 2007. <http: //www.calendar live.com/movies/reviews/cl-movie 980305-8,0,5350785.story>.

Warshow, Robert. The Immediate Experience: Movies, Comics, Theatre and Other Aspects of Popular Culture. New York: Doubleday, 1962.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Culture and Value. Ed. G. H. Von Wright. Trans. Peter Winch. London: Blackwell, 1980.

Notes

(1) I have written elsewhere of the possibly Orwellian implications of such perversely contrary critical disagreement (Lavery, "’Coming Heavy’" xiii). But the root cause of such disputes, as I argue here, may not be political or even ideological.

(2) Jameson is thinking of Miller’s Crossing’s opening scene, in which Johnny Caspar asks Irish mob boss Leo O’Bannon for permission to whack Bernie Bernbaum. Leo denies his request, a decision criticized by consigliere Tom Reagan, setting in motion the film’s entire narrative.

(3) Ebert finds himself so split on the subject of the Coens that he proffers a schizophrenic review of The Hudsucker Proxy with opinions by both his "angel" (four stars) and his "devil" (zero stars).

(4) In The Coen Brothers, Ronald Bergan quotes the following passage from Ethan Coen’s thesis, "Two Views of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy":

Is it a matter of the believer's operating with a more sophisticated conceptual apparatus, which he might bring us (nonbelievers--hello out there) to share by means of some fancy dialectic? No--this isn't how people become religious. Is the believer smarter than we are? No. I'm not saying that he's stupid. I'm saying that I can't imagine what sorts of distinctions he could draw to make his statement make sense for me. And the Catholic's insistence that it is literally the blood and body of Christ that he eats--he wants to emphasize that he gives those words no special sense, that he didn't 'have recourse' to them for want of better--underscores the point that here we haven't to do with some quasi-scientific insight. (63)

(5) Both on and off the set, il poeta was a fabulous liar. (Fellini’s wife, Giulietta Masina, once observed that "Federico only blushes when he tells the truth.") During the filming of La Dolce Vita (1960), for instance, Fellini warned the paparazzi that the famous American actress Dolly Grande would be on set for the next day’s filming. The press, of course, showed up in force only to discover that, true to its name, Dolly Grande was a large dolly needed for a particular shot. On another occasion, when caught by an interviewer anxious to prove him a liar, Fellini defended himself by insisting that, as a professional storyteller, it was his duty to tell such tales (Lavery, "Major Man" 17). Needless to say, such a stance did not sit well with certain critics. In The Biographical Dictionary of Film, to cite but one example, Thomson, with even more ire than he showed the Coens, assaults Fellini as "a baroque inauthentic fantasist, an egotistical purveyor of self-indulgent, needlessly enigmatic visions … [an] obsessional vacuous poseur … a half-baked, play-acting pessimist, with no capacity for tragedy," whose films are a "doodling in chaos" (236).

(6) As confidence men, the Coens are part of a distinctly American literary tradition as well. The classic fictional portrait of the flimflam man as an American type is, of course, Herman Melville’s 1854 novel The Confidence Man. Major American literary figures from Mark Twain to William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor likewise depicted him, and Twain and Faulkner themselves engaged in literary cons, often intended to deceive and mislead critics.

(7) The director of the Bar Kochba, Rabbi Emmanuel Lev-Tov, we also learn, edits the quarterly journal "T’keyah and wrote a memoir entitled You with the Snozz.

(8) Representative of Ethan Coen’s poetry is the short piece "Retirement Plan":

Someday I'll set aside my pen And have the time to practice Zen, Reflect, read Proust and Moby Dick And Heidegger, and pull my prick. (96)

(9) Landor (1775-1864) was a British Romantic writer and poet, author of Imaginary Conversations of Literary Men and Statesmen (1824-1829).

(10) The Coens also spoof academic excess in the introduction to the Hudsucker Proxy screenplay, purportedly the work of the utterly fictional Dennis Jacobson, professor of cinema studies at the University of Iowa, who in turn interviews the utterly real (though larger than life) Joel Silver, the blockbuster-driven Hollywood mogul who bankrolled the big-budget Hudsucker.

(11) Turan’s favorite example comes from The Big Lebowski, when The Stranger, a cowboy who has somehow stumbled into the film-noirish comedy out of his proper home in a Western, says, "It was a pretty good story, don’t you think? It made me laugh. Parts of it anyway" (140).

(12) This comment comes upon the moment, described by Billy Bob Thornton as his "first gay scene," in which Ed Crane stands in the doorway of the hotel room of Creighton Tolliver.

(13) For a more detailed explanation of Miller’s theory of the mise-en-abyme, see my "O Lucky Man! and the Movie as Koan" (35-36).

(14) The Coens, McKinney notes, "are darker-souled than Tarantino and also less obsessed with fun at any cost, and though they are temperamentally incapable of aggressively confronting an audience as Spike Lee does, they are still too involved in the oddities of their imagination to affect the Jarmusch shrug" (31).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.