LEBOWSKI …it’s funny. I can look back on a life of achievement, on challenges met, competitors bested, obstacles overcome…I’ve accomplished more than most men, and without the use of my legs. What…What makes a man, Mr. Lebowski?

DUDE Dude.

LEBOWSKI …Huh?

DUDE I don’t know, sir.

LEBOWSKI Is it…is it, being prepared to do the right thing? Whatever the price? Isn’t that what makes a man?

DUDE That, and a pair of testicles.

LEBOWSKI …You’re joking. But perhaps, you’re right…

— From “The Big Lebowski”, Screenplay by Joel and Ethan Coen

INTRODUCTION

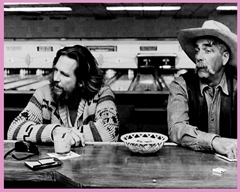

Testicles. This is the agreed upon definition of masculinity between two men named Lebowski. Jeffrey Lebowski, referred to as “The Dude”, is a long-haired, unkempt and shabbily dressed unemployed white male bachelor who spends his time drinking cheap beer at bowling tournaments while evading the rent collector. The Big Lebowski is a wealthy older white male who displays a multitude of plaques for civic achievements on the walls of his home office within his lavish estate. They seem like two estranged ends of the see-saw of male success, one socially powerful and the other socially powerless, but in the film The Big Lebowski we find that both Lebowski’s are wrestling with the white heterosexual male hegemonic identity and can root all of their personal conflicts and actions as an attempt to reclaim their male identity. Their territorial trouble together supposedly begins because of a rug, but behind the trouble is a woman, and as the film unfolds, the narrative reveals that the greatest threat to the male code is not other men, but other women.

CRITIQUING THE CRITICS

In the introduction to the screenplay there is an excerpt from a film review by Sir Anthony Forte-Bowell, the editor of the prominent film journal Cinema/Not Cinema, and he states with scholarly authority that:

In the introduction to the screenplay there is an excerpt from a film review by Sir Anthony Forte-Bowell, the editor of the prominent film journal Cinema/Not Cinema, and he states with scholarly authority that:

Repeated viewings of the movie have failed to clarify for me the genre-relevance of the themes of bowling, physical handicap, castration, and the Jewish Sabbath. But perhaps we should not dismiss the possibility that they are simply authorial mistakes. Certainly the script could not be held up as a model of artistic coherence (viii).

Forte-Bowell’s overwhelmingly negative criticism of the film is concurrent with popular opinion. The film has been described by mainstream critics as a contemporary film noir tribute to The Big Sleep, a nonsensical narrative of bowling and drug humor that has no plot or purpose, and overall an unsuccessful film by normally reputable directors, The Coen Brothers. The theatrical release in 1998 was met with mild box office attention and considered a “bomb”, to use the parlance of our times.

Yet, nearly a decade later, the film has become a cult phenomenon, with annual “Lebowski Fests” popping up in every state, where fans dress up as their favored characters to enjoy a night of bowling while knocking back White Russian cocktails (referred to in the film as a “Caucasian”) and mingling with actors who held supporting or minor roles in the film. The newfound popularity of The Big Lebowski is testament to the film’s ability to resonate with American audiences, and perhaps a calling to scholars and critics to re-examine the disappointment of their first impressions.

After days of academic research, I was only able to recover one serious examination of the film that thoroughly explored the themes of male mythology and conflict in the film. Todd Comer’s essay, “’This Aggression Will Not Stand’: Myth, War, and Ethics in The Big Lebowski” discusses Walter Sobchak’s (The Dude’s closest friend and bowling partner) aggressive behavior in terms of his lack of closure with his Vietnam war experience and his character parallels to President George Bush Sr.’s initiation of military conflict in the Persian Gulf as a response to his experiences as a veteran of World War II.

Comer’s argument is significant as Walter is constantly placing his civilian conflicts in terms of the Vietnam War, and references to the Persian Gulf War are peppered throughout the film. For example, the opening narration places the story in “the early nineties—just bout the time of our conflict with Sad’m and the Eye-rackies” and in the opening scene where The Dude is checking out at the grocery store, a television in the background broadcasts footage of President Bush’s response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait: “This aggression will not stand…This will not stand!” This line is repeated by The Dude when he speaks to The Big Lebowski, and returns again in recent history as the younger President Bush responds to the 9/11 attacks by stating, “Terrorism against our nation will not stand” (Comer, 111).

Through Comer’s perspective, the rug appears to be military territory, where the Persian Rug is tied to the Persian Gulf. Unfortunately, Comer does not acknowledge that the rug actually belonged to Maude Lebowski as a gift from her mother, which significantly defines it as female territory. While Comer makes minimal reference to castration anxiety in the film’s dream sequences, he does not make any connection between the male mythology and the relationships of the male characters to their female counterparts. The themes of conflict in The Big Lebowski cannot be interpreted in isolation from the themes of male and female power, as I will demonstrate.

Through my perspective, the rug is tied to women, as “rug” is a common, although unflattering, slang term for female genitalia. Using scholars Chris Wienke, Bryce Traister, and Ronald Levant’s research on the crisis of masculinity as support for my argument, I will argue that the film strongly emphasizes the male crisis and its relationship to female power. Both perspectives acknowledge that on the surface, this is a comedic film about bowling and male bonding, but just below the celluloid surface, this is a serious film about male power and/or lack thereof. Traister writes in, “Academic Viagra: the Rise of American Masculinity Studies”:

That the men formerly (and still) regarded as paragons of normative masculinity stand revealed as anxious failures by the crisis theory of heteromasculine historiography may provide some comfort to the less successful, the less normative, the less erect—that is, the less ‘masculine’—among us (292).

The Big Lebowskibrings these “less normative” males to the foreground in the role of the narrative hero, allowing us a closer look at the environment and psychology that fuels their actions.

MAUDE AND THE ANATOMY OF BOWLING

The opening credits of the film roll to the sounds of Bob Dylan’s song (1970), “The Man in Me”, whose lyrics repeat in chorus: “Take a woman like you to get through to the man in me.” Here we find the first reference to a man defining himself in terms of his relationship to a woman. The woman that gets through to Jeffrey Lebowski (A.K.A. The Dude) is Maude Lebowski, an iconic figure of feminism, a successful painter who works in the nude and whose artwork has been applauded by critics as being “strongly vaginal.” Her dialogue is direct and confrontational as she states, “The word itself makes some men uncomfortable. Vagina.” The Dude responds with a passive silence as she continues, “Yes, they don’t like hearing it and find it difficult to say. Whereas without batting an eye a man will refer to his ‘dick’ or his ‘rod’ or his ‘Johnson’.”

This is a woman who demands linguistic equality with men, and who does not allow The Dude to keep the rug that he has stolen from The Big Lebowski to replace his own rug that was damaged by thugs who made their threats in the wrong apartment. The rug is important because The Dude initially laments that the rug, “really tied the room together–.” In a sense, it is a rug that completes his living space, and now as a missing element, he feels incomplete. As a bachelor, the rug has become a replacement for a woman in his life, as he yells at the thugs during their attack, “…You see a wedding ring? Does this place look like I’m fucking married? The toilet seat is up!” By taking back the rug, Maude insures that The Dude remains in this state of incompleteness.

This is a woman who demands linguistic equality with men, and who does not allow The Dude to keep the rug that he has stolen from The Big Lebowski to replace his own rug that was damaged by thugs who made their threats in the wrong apartment. The rug is important because The Dude initially laments that the rug, “really tied the room together–.” In a sense, it is a rug that completes his living space, and now as a missing element, he feels incomplete. As a bachelor, the rug has become a replacement for a woman in his life, as he yells at the thugs during their attack, “…You see a wedding ring? Does this place look like I’m fucking married? The toilet seat is up!” By taking back the rug, Maude insures that The Dude remains in this state of incompleteness.

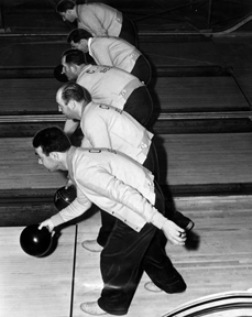

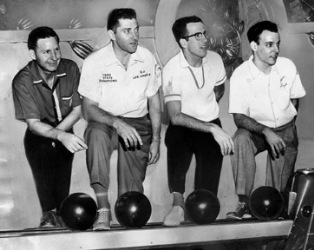

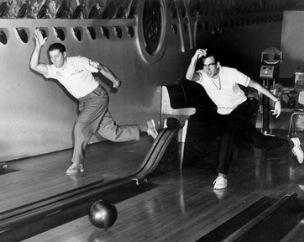

Another female surrogate employed by The Dude and his fellow bachelors is bowling. It is not a stretch to suggest that bowling pins are phallic in shape, and that roundness, like the bowling ball itself, is commonly associated with femaleness. The object of bowling is for the bowler to insert his fingers into the three holes of the bowling ball to control the

movement of the bowling ball in order to knock over the standing pins at the end of the lane. As bowling is popularly the past time of white males, we can conclude that symbolically bowling is the act of a male figure exerting his control over the female figure to establish dominance over other male forms. The three holes can be referred to as the three physical holes in a woman’s genitalia (vagina, urethra, and anus) or the three holes of male penetration (vagina, anus, and mouth). In either instance, the bowling ball is a sexual object, and therefore the dominance that a man must exert is now focused on sexual dominance.

While the theory of woman as bowling ball may seem like a ridiculous academic reach for symbolic association, let us look closely at the evidence for this notion in the film. When Maude reclaims her rug from The Dude’s apartment, her bodyguards knock The Dude unconscious leading into an extensive dream sequence that plays out over the repetition of the opening theme song, “The Man in Me”. The Dude is flying over Los Angeles, following an elusive woman on a magic carpet who is always just out of arm’s reach. As The Dude recognizes that his hand is in a bowling ball, the dream unites the primary symbols of bowling ball, woman, and rug in the Dude’s subconscious. As the bowling ball affects his  dream gravity, The Dude is hurtled towards the city and finds himself on the bowling lane in miniature standing in the path of a giant rumbling bowling ball. In his shrunken size, he has become the pin about to be overpowered by the ball. As the ball overtakes him, he falls through the hole and the point of view is, “that of someone trapped in the thumb hole of the rolling ball.”

dream gravity, The Dude is hurtled towards the city and finds himself on the bowling lane in miniature standing in the path of a giant rumbling bowling ball. In his shrunken size, he has become the pin about to be overpowered by the ball. As the ball overtakes him, he falls through the hole and the point of view is, “that of someone trapped in the thumb hole of the rolling ball.”

This sense of the interior space of the bowling ball is repeated when The Dude visits Maude’s loft. At the opening of the scene, the sound direction reads: “We hear a rumble like that of an approaching bowling ball” and the shot centers The Dude in a large darkened room framed by light entering through the doorway far in the background. Maude’s dark loft then is the interior of the bowling ball, and the lit doorway the thumb hole through which he entered. Maude sails naked over The Dude as the sounds of the rumbling ball grow louder, as she is attached to a sliding sling mechanism that allows her to fly over her canvas while splattering paint onto her “vaginal” art. Her movements simulate the action of a bowling ball gliding down the lane, and instead of pins, there is the completion of her art that has lead to her social and economic success, making her significantly more powerful than The Dude.

CRACKING THE MALE LEBOWSKI CODE

As bachelors, The Dude and his bowling team demonstrate a complete lack of dominance over women, and therefore their masculinity is in question as long as they subscribe to the white male heterosexual hegemonic code that supports the concept that to be manly, a man must be more powerful than a woman. Levant argues in, “The Masculinity Crisis” that the rise of women’s economic power due to the progress of feminism has displaced the male role as the primary provider to whom women had been previously dependent:

The loss of the good-provider role brings white, middle-class men closer to the experience of men of color and the lower class, who (albeit for very different reasons) have historically been impeded from being the economic providers for their family, and consequently, have experienced severe gender role strain (3).

Men, recognizing that a woman no longer needs a man financially to raise a family, has yet to find a new role to replace this out-dated provider role because he still clings to the traditional concepts of manhood, unable to find a suitable alternative. Levant also states that the role of Fathering has yet to gain importance as a primary provider role replacement because men still consider the stay-at-home father who is present and involved in the lives of his children to be a man taking on a female gender behavior, therefore considered an emasculated male.

Maude understands and takes advantage of this male psychology by engaging sexually with The Dude for the sole purpose of conception, telling him: “Look, Jeffrey, I don’t want a partner. In fact I don’t want the father to be someone I have to see socially, or who’ll have any interest in rearing the child himself.” To this, The Dude again responds with passive silence and acceptance, thereby acknowledging that he still adheres to the white male heterosexual male code, despite his overwhelming “failure” of meeting the expectations of this mythological standard.

On these economic terms, The Dude and The Big Lebowski have been equalized. Maude reveals that despite his social status, The Big Lebowski has no real money of his own and lives on an allowance from his late wife’s wealth and administering the charities under his daughter. She states, “We did let Father run one of the companies, briefly, but he didn’t do very well at it.” Therefore his wall of plaques and honors were made possible by his late  wife’s success as the family provider. Nevertheless, he spouts the rhetoric of male social achievement as he describes the ineptitude of his second wife’s supposed kidnappers: “As you can see, it is a ransom note. Sent by cowards. Men who are unable to achieve on a level field of play. Men who will not sign their names. Weaklings. Bums.”

wife’s success as the family provider. Nevertheless, he spouts the rhetoric of male social achievement as he describes the ineptitude of his second wife’s supposed kidnappers: “As you can see, it is a ransom note. Sent by cowards. Men who are unable to achieve on a level field of play. Men who will not sign their names. Weaklings. Bums.”

Bunny Lebowski, his second wife, is also tied to the rug trouble because her debt to known pornographer Jackie Treehorn is what prompted the thugs to land at The Dude’s apartment to begin with. She is a young porn starlet whom the Big Lebowski has clearly married because of her sexual power over him, and she uses this sexuality as means for economic gain, again removing the male from the role of primary provider. As The Dude and Walter confront The Big Lebowski on his false masculine pretenses, he screams through his tears, “Stay away from me! You bullies! You and these women! You won’t leave a man his fucking balls!” Here we return to the theme of testicles, suggesting that this physicality is all that remains of The Big Lebowski’s claim to male identity.

MEN’S BODIES, MEN’S SELVES (A.K.A. PHALLUS ANALYSIS)

In the essay, “Negotiating the Male Body: Men, Masculinity, and Cultural Ideals,” Wienke interviews a selection of men on their perspectives of the ideal male physicality and the relationships of their own bodies to this ideal. He states that in response to recent political gains by women, there has been a “remasculinization of America” as evidenced by “the on-screen visual presentation of the male body, as bulging muscles, rock-hard physiques, and a fusion of male bodily power with machines (weapons, mostly)” as “celebrated features of some of Hollywood’s most extravagant productions” (3). His respondents commonly refer to this hyper-masculine image as the cultural ideal to which they compare and judge themselves and others, with the majority of males feeling that they fell short of these standards.

In the essay, “Negotiating the Male Body: Men, Masculinity, and Cultural Ideals,” Wienke interviews a selection of men on their perspectives of the ideal male physicality and the relationships of their own bodies to this ideal. He states that in response to recent political gains by women, there has been a “remasculinization of America” as evidenced by “the on-screen visual presentation of the male body, as bulging muscles, rock-hard physiques, and a fusion of male bodily power with machines (weapons, mostly)” as “celebrated features of some of Hollywood’s most extravagant productions” (3). His respondents commonly refer to this hyper-masculine image as the cultural ideal to which they compare and judge themselves and others, with the majority of males feeling that they fell short of these standards.

The men in The Big Lebowski embody symbolic opposites of this iconic male: Walter is excessively overweight, Donny is excessively underweight and sickly, and The Dude resembles a man whose abdomen perhaps was once ideal in his youth but now resembles a shirt-stretching beer belly. The Big Lebowski is a senior with a war injury that has left him physically disabled and resigned to a wheelchair. In Wienke’s research, men who feel that they do not meet the cultural standard find ways of compensating for this difference in other areas of their lives:

For example, if an individual cannot meet the masculine ideals of physical strength and toughness, he can at least distance himself from these standards by placing value on mental strength or emotional toughness, standards that may reflect what he is actually capable of accomplishing. A third response is to reject actively the dominant masculine model, and either view masculinity as having little importance in their lives or construct an alternative masculine identity (5).

Walter’s coping strategy is to respond to challenges with excessive violence and military aggression, while The Big Lebowski, also a war veteran, compensates for his physical shortcomings by being abnormally active in civic life: “I didn’t blame anyone for the loss of my legs, some Chinaman in Korea took them from me, but I went out and achieved anyway.” The Dude responds to the male role by dismissing its importance and abiding by a slacker anti-social non-participatory mentality. Donny, the most non-muscular and  therefore the most effeminate of the males, dies of heart failure when Walter and The Dude engage in physical combat with the Nihilists in the parking lot of the bowling alley.

therefore the most effeminate of the males, dies of heart failure when Walter and The Dude engage in physical combat with the Nihilists in the parking lot of the bowling alley.

Donny significantly dies without throwing or receiving a single punch, suggesting that those males without a coping strategy or alternative cannot survive as men. When The Dude expressed fear of castration by the Nihilists by exclaiming, “I need my fucking Johnson!” Donny responds by asking, “What do you need that for, Dude?” His inability to relate to the importance of the male body in defining masculinity is a predecessor to his demise. In contrast, the women in the film both maintain idealized feminine physicalities, reinforcing the concept that physical beauty is associated with access to power.

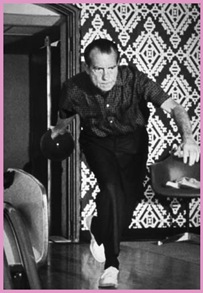

There are a few other notable references in the film that reinforce the significance of the phallus as essential to any interpretation. In The Dude’s apartment there is a large poster of Richard Nixon bowling presented altar-like on the wall above the bar.

There are a few other notable references in the film that reinforce the significance of the phallus as essential to any interpretation. In The Dude’s apartment there is a large poster of Richard Nixon bowling presented altar-like on the wall above the bar.

Nixon has been historically nicknamed “Tricky Dick” and his impeachment, or fall from power, resonates with the themes of emasculation. When The Dude confronts a man that has been following him, he discovers that the man is Da Fino, a private investigator hired by Bunny’s family. He tells him that he is “a dick, man!” and that The Dude is a dick as well. Jackie Treehorn absurdly sketches a penis on a pad of paper when The Dude visits his party. And Walter uses a suitcase full of his dirty underwear, the fabric that protects and supports his loins, as the ringer for the payment to the kidnappers.

THE STRANGER AND THE DUDE

What places this narrative in the context of the white heterosexual male is the framing of the story by the narration of a cowboy, portrayed by Sam Elliot, an actor popular in Hollywood Westerns. The typical cowboy stereotype is a tough, white male bachelor who fights for alpha male dominance in the Wild West. As The Big Lebowskiopens by panning contemporary Los Angeles to the country tune of Tumbling Tumbleweeds, the audience finds that we are still in the Wild West, but the dude that used to rope horses, is now The Dude in the form of Jeffrey Lebowski, and the archetypal cowboy is his mythological male ancestor.

In fact, the only people with whom the cowboy exchanges dialogue is The Dude, and the viewing audience. This mythical male symbolizes the origins of the American male hegemonic code, and although it is antiquated, it remains the essential ideal and therefore problematic:

Thus some men cling to a version of reality that is becoming increasingly mythical as time goes on. I think this goes to the heart of the matter, namely, that men identify so strongly with the code of masculinity that they are more likely to distort reality than to question the code. Why do men do this? Certainly the power and prerogatives that come with being a man in a patriarchal society would make it advantageous to cling to the code (Levant, 3).

The Dude is a heroic distortion of this historical male identity, and the emphasis on race as part of this identity is presented through his constant ordering of a White Russian cocktail which he refers to as a “Caucasian”. The White Russian is a drink named after the losing army in Russia’s October Revolution, therefore The Dude’s beverage of choice is the drink of social failures, a subtle reference to The Dude’s passive acceptance of his social shortcomings.

The character of The Dude is based on real-life Jeff Dowd, who is reputed to “drink people a third of his age under the table” according to Lebowski Fest organizers (Edelstein, New York Times). Both Jeff’s prefer to be referred to as “The Dude” as one Lebowski explains to the other: “I’m not Mr. Lebowski; you’re Mr. Lebowski. I’m the Dude. So that’s what you call me. That, or Duder. His Dudeness. Or El Duderino, if, you know, you’re not into the whole brevity thing—.” The repetition of the term “Dude” is important to the hegemonic male code because of its equalizing intent; dude is expressed from one peer to another, therefore neither male is considered to have power over the other, eliminating the need for conflict or competition. In Scott Kielsling’s thorough linguistic analysis of “Dude”, he concludes that the term is primarily used in male/male interactions to establish cool solidarity, strict heterosexualty, and nonconformity:

Dude helps men maintain this balance between homosociality and hierarchy. It is not surprising, then, that dude has spread so widely among American men because it encodes a central stance of masculinity (298).

When Lebowski requests to be referred to as The Dude, he is demanding non-confrontational yet equal social status with other males, including the elitist Big Lebowski. While Kiesling acknowledges that dude is used by young women, its occurrence in female speech is minimal compared to its lopsided presence in male dialogue.

FORTHCOMING RESEARCH

I realize my discussion has left out further exploration of the role of masculinity in Walter’s relationship to his ex-wife and his conversion to Judaism, as well as the themes of castration anxiety in The Dude’s second dream sequence.

There is also much to be discussed regarding the character of Quintana, their bowling nemesis and known sexual predator of children. The unsolved mystery of Larry Sellers’ homework in The Dude’s car, and the significance of his father, an admired writer for the television series Branded, being kept alive in an iron lung are also of importance.

Comer does give attention to the relationship between Branded and the effects of the war experience on male identity, but makes an unconvincing argument for a symbolic connection between the characters of Larry and Donny. I would like to steer further analysis to the connection between my gendered perspective and Comer’s military perspective by suggesting Vaheed Ramazani’s essay, “The Mother of All Things: War, Reason, and the Gendering of Pain”. Ramazini demonstrates a connection between war and childbirth through their linguistic parallels:

It might then not be entirely inaccurate to say that revolutions ‘are’ the labor pains preceding the birth of new societies. Relative to certain purposes, contexts, or outcomes, it might not be inaccurate to describe war as the ‘mother’, the ‘matrix’ of a given culture, or to find historical evidence for the philosophical adage that, in the absence of occasional military conflict, nations lie ‘fallow,’ turn ‘barren,’ or fall ‘sterile’ (30).

Because war and feminine sexuality are both tied into the rug at the center of The Big Lebowski, we must conclude that there is a relationship between the themes and a topic worthy of further research.

CONCLUSION

The cult of Lebowski grows up along with masculinity studies as the increase of non-normative males take lead roles in popular narratives. Invincible male icons such as James Bond and Batman are steadily being displaced by unlikely heroes like Frodo, a timid hobbit of small stature, or Harry Potter, the visually impaired yet prolific child magician. The alternative masculine heroes, even flawed ones as in The Big Lebowski, give important attention to the construction of a new male identity:

The cult of Lebowski grows up along with masculinity studies as the increase of non-normative males take lead roles in popular narratives. Invincible male icons such as James Bond and Batman are steadily being displaced by unlikely heroes like Frodo, a timid hobbit of small stature, or Harry Potter, the visually impaired yet prolific child magician. The alternative masculine heroes, even flawed ones as in The Big Lebowski, give important attention to the construction of a new male identity:

Like the countless men whose erections, we are now finding out, have been for some time anything but firm and energetic, American masculinity emerges in the pages of heteromasculinity scholarship as troubled, distracted, counterfeit, constructed, masked, performative, flaccid, domestic, tender, and feelingful (Traister, 284).

As the myth of manhood continues to be deconstructed, men may be able to release the steady grip on their testicles that they have held for centuries, thereby allowing healthy circulation to the weak phallus of male identity, mapping out new male territory where they can be both confident and erect.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coen, Ethan and Joel. “Introduction: Lebowski Yes and No”. The Big Lebowski Screenplay. London: Faber and Faber, 1998.

Comer, Todd. “’This Aggression Will Not Stand’: Myth, War, and Ethics in The Big Lebowski.” SubStance #107 34.2 (2005): 98-117.

Dylan, Bob. The Man in Me. Big Sky Music, 1970.

Edelstein, David. “You’re Entering a World of Lebowski.” New York Times 8 Apr. 2004, late ed., sec. 2: 21+.

Kiesling, Scott F. “Dude.” American Speech 79.3 (2004): 281-305.

Levant, Ronald F. “The Masculinity Crisis.” The Journal of Men’s Studies 5.3 (1997): 221+.

Ramazani, Vaheed. “The Mother of All Things: War, Reason, and the Gendering of Pain.” Cultural Critique 54 (2003): 26-66.

The Big Lebowski. Dir. Joel Coen. Perf. Jeff Bridges, John Goodman, Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi, and John Turturro. Polygram/Filmed Entertainment, 1998.

Traister, Bryce. “Academic Viagra: the Rise of American Masculinity Studies.” American Quarterly 52.2 (2000): 274-304.

Wienke, Chris. “Negotiating the Male Body: Men, Masculinity, and Cultural ideals.” Journal of Men’s Studies6.3 (1998): 255+.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.