by Rev. Oliver Benjamin

When writers look for a way to inject gravitas into a subject, they often resort to the common ploy of examining the origins of words, or etymology. A critic of democracy might say, for instance: “Politics comes from the Greek word for “city”, which is why people living out in the countryside should not be allowed to vote.” Don’t object –- the great thing about etymology is that you can use it to make any point you like.

When writers look for a way to inject gravitas into a subject, they often resort to the common ploy of examining the origins of words, or etymology. A critic of democracy might say, for instance: “Politics comes from the Greek word for “city”, which is why people living out in the countryside should not be allowed to vote.” Don’t object –- the great thing about etymology is that you can use it to make any point you like.

Yet etymology is only the presumed history of a word, and history is always a flawed interpretation. As feminists sometimes facetiously point out, history itself comes from the words “his” and “story.” Thus, not only is etymology an inexact science, but it’s easily co-opted by those with political (from the Greek: poly = many, tickle = irritating sensation) interests. What’s your story, dude?

Fickle as they might be, the histories of individual words can shed illumination on, if not on the truth, then on what we might imagine truth to be like. This is why words with controversial etymologies are the most interesting of all: They are lightning rods for the mass imagination. “Dude” is one such term that carries with it not only rich historical baggage, but has also produced a broad Diaspora of meanings.

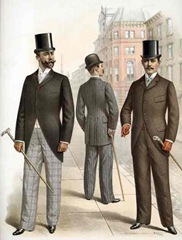

According to that monolithic temple to English etymology, The Oxford English Dictionary, the word “dude” was birthed in New York in 1883, as a way to describe a certain fad of the time, an exaggerated foppishness among young men which was seen as an attempt to appear “British.” This sudden fad may have been precipitated by the fact that Oscar Wilde visited New York in 1882 and was at that time the Western world’s most celebrated author and pre-eminent fop. This is not to say that he or they were mere narcissists. Just as today’s rock personalities manufacture affectations and overdoses of style, Oscar Wilde was the Puff Daddy of 19th century literature and the New York dudes fans and imitators of his “outsider art.”

According to that monolithic temple to English etymology, The Oxford English Dictionary, the word “dude” was birthed in New York in 1883, as a way to describe a certain fad of the time, an exaggerated foppishness among young men which was seen as an attempt to appear “British.” This sudden fad may have been precipitated by the fact that Oscar Wilde visited New York in 1882 and was at that time the Western world’s most celebrated author and pre-eminent fop. This is not to say that he or they were mere narcissists. Just as today’s rock personalities manufacture affectations and overdoses of style, Oscar Wilde was the Puff Daddy of 19th century literature and the New York dudes fans and imitators of his “outsider art.”

These embryonic dudes were emulators of what was once referred to as “the leisure class,” a state once seen as the goal mankind’s evolution – from caveman to farmer to merchant to man of leisure, where a society’s economic surplus has become so great that one hardly need work at all. It was the pot at the end of the rainbow, one which until very recently everyone thought was just around the corner. Sadly, we now know better. There may never be a perpetual motion machine, a robot underclass, or even a free lunch. Even Bill Gates still works his ass off.

But where did the word itself come from? Most linguists seem to think it was a variation on “dandy.” Changing the “a” sound for an “oo” sound had long been a common way of humorously playing with word sounds: the slang word skeedaddle (to exit rapidly) was often changed to skeedoodle, as it still is today. Thus dandy became “doody” and even “doodle,” the latter making it into the British song “Yankee Doodle Dandy” which was popular just prior to the revolutionary war in 1776. The song was meant to make fun of poor colonists whose provincial fashions were no match for British sartorial might. They were too low-class to be true doodles, as the song goes, sticking feathers in their modest caps and undeservedly calling it “macaroni” (slang for Italian tailoring, which was just as highly regarded then as it is today).

But where did the word itself come from? Most linguists seem to think it was a variation on “dandy.” Changing the “a” sound for an “oo” sound had long been a common way of humorously playing with word sounds: the slang word skeedaddle (to exit rapidly) was often changed to skeedoodle, as it still is today. Thus dandy became “doody” and even “doodle,” the latter making it into the British song “Yankee Doodle Dandy” which was popular just prior to the revolutionary war in 1776. The song was meant to make fun of poor colonists whose provincial fashions were no match for British sartorial might. They were too low-class to be true doodles, as the song goes, sticking feathers in their modest caps and undeservedly calling it “macaroni” (slang for Italian tailoring, which was just as highly regarded then as it is today).

Distilled from “doodle” (dandy), the shortened form “dude” makes its first appearance in print in a poem by one Robert Sale Hill in 1883 which lampoons the new breed of idle, fashion-conscious males. Despite this hard evidence, alternative ideas still abound, most plausibly that it comes from “duds” or nice clothes. Another idea is that it comes from “Duke” the ruler of a provincial state, or even a rustic German word meaning “fool.”

In any event, dudes did ultimately take the path of foolhardy, provincial royalty by heading out into the countryside. As members of the re-engineered idle class, they were obligated to venture forth and enjoy the fruits of their leisure, and they did so by becoming landed gentry in a land where doing so was far cheaper and easier than it was in England. Forced to mix with the threadbare locals, they soon warmed to the pioneering ways and word got back to the city that the romantic living atop a horse was preferable to the filthy industrialized New England cities, even if only for a few weeks at a time. This resulted in the famous “dude ranches,” where city-slickers traded their top hats for early prototypes of the ten-gallon variety and learned to shout “yippie kai yay!” without sounding overly effete.

In any event, dudes did ultimately take the path of foolhardy, provincial royalty by heading out into the countryside. As members of the re-engineered idle class, they were obligated to venture forth and enjoy the fruits of their leisure, and they did so by becoming landed gentry in a land where doing so was far cheaper and easier than it was in England. Forced to mix with the threadbare locals, they soon warmed to the pioneering ways and word got back to the city that the romantic living atop a horse was preferable to the filthy industrialized New England cities, even if only for a few weeks at a time. This resulted in the famous “dude ranches,” where city-slickers traded their top hats for early prototypes of the ten-gallon variety and learned to shout “yippie kai yay!” without sounding overly effete.

As decades passed and those landed gentry became tougher and more authentically rural, “dude” became an old wild-west term for “big boss.” And there it remained until re-adopted in the mid-20th century by American Blacks looking to describe the “big bosses” of their own ghettos, their answer to the British dandy of decades earlier, namely the eminently-outfitted and admired (at least by young males) street-corner pimps. It is hard not to notice here an earthward vector for the once-frilly dude of late 1800s New York: From cravat to cowboy boots to capped teeth, this is a vector that has neatly mirrored the entire calculus of outsider cool throughout modern American culture.

Around the middle of the 1900s the greatest source of this calculated coolness for US Anglos was blacks themselves, and so, in a manoeuvre that would come to characterize most black-white cultural exchange, the whites stole “dude” from the blacks. This time it didn’t matter as the blacks stole it from the whites in the first place. Finally, completing the circle, dude made it to Britain in the 70s, where it became a popular term of endearment in the gay and foppishly glam-rock communities, and enshrined in David Bowie’s tune “All the young dudes.”

Around the middle of the 1900s the greatest source of this calculated coolness for US Anglos was blacks themselves, and so, in a manoeuvre that would come to characterize most black-white cultural exchange, the whites stole “dude” from the blacks. This time it didn’t matter as the blacks stole it from the whites in the first place. Finally, completing the circle, dude made it to Britain in the 70s, where it became a popular term of endearment in the gay and foppishly glam-rock communities, and enshrined in David Bowie’s tune “All the young dudes.”

However, the explosive growth of the term, fueled by US Anglos, would come to contradict its earlier aesthetic. In the US, “dude” travelled among the beatniks of the ‘50s to the hippies of the ‘60s, and ultimately to the surfers of the ‘70s, until it became slowly purged of all its pretentiousness, ultimately describing virtually anyone, male or female, as long as they weren’t uptight, square, or enslaved to the system. The dude was still an outsider, of course, but a powerless, impoverished and consequently an increasingly egalitarian one. “The Dude” character in The Big Lebowksi is of course the torch-bearer for the tradition, a man who retains all the laziness of the fop with absolutely none of the cash, something that should please both dedicated capitalists and couch potatoes equally.

Dudeism has come to the end of the road. Today, at long last, we are all of us dudes, probably because rich or poor, right wing or left, nearly everyone considers themselves outsiders to the “system.” Even old fashioned conservatives who call themselves the “moral majority” see themselves as embattled by intellectual media and international opinion and show their rebellion by forming shriekingly bad Christian heavy metal bands. Everyone is dudelier-than-thou now, and for good reason. The more multifarious fashions and pastimes and tastes and opinions become, the more chances we all have to literally wear our hearts on our sleeves, and the greater the importance of finding a way to distinguish ourselves amongst the muddle of population, information and amplified ululation.

Dudeism has come to the end of the road. Today, at long last, we are all of us dudes, probably because rich or poor, right wing or left, nearly everyone considers themselves outsiders to the “system.” Even old fashioned conservatives who call themselves the “moral majority” see themselves as embattled by intellectual media and international opinion and show their rebellion by forming shriekingly bad Christian heavy metal bands. Everyone is dudelier-than-thou now, and for good reason. The more multifarious fashions and pastimes and tastes and opinions become, the more chances we all have to literally wear our hearts on our sleeves, and the greater the importance of finding a way to distinguish ourselves amongst the muddle of population, information and amplified ululation.

Proceeding even further in its emancipation, the word “dude” has come to the point where it no longer even requires a subject – it has become a wholly ethereal entity with no fixed meaning at all, like God. This is proved in a pivotal scene in the 1998 comedy BASEketball where Trey Parker and Matt Stone (of South Park fame) engage in a hilarious minute-long conversation employing only different inflections of “dude.” Oscar Wilde, it may not be, but the scene goes a long way to show how meaningless words can be in and of themselves. (Later, Bud Light took the same idea and employed it in an effective commercial.*)

Proceeding even further in its emancipation, the word “dude” has come to the point where it no longer even requires a subject – it has become a wholly ethereal entity with no fixed meaning at all, like God. This is proved in a pivotal scene in the 1998 comedy BASEketball where Trey Parker and Matt Stone (of South Park fame) engage in a hilarious minute-long conversation employing only different inflections of “dude.” Oscar Wilde, it may not be, but the scene goes a long way to show how meaningless words can be in and of themselves. (Later, Bud Light took the same idea and employed it in an effective commercial.*)

What the history of “Dude” shows is that what matters is what words mean to you at this moment in time. And perhaps more than any modern word, dude shows us that words change, ideas change, opinions change, and that we have to respect this. Ironically, this notion happens to be central to the core of Dudeist philosophy.

Etymology is often nothing more than a history of fashion, an ancient armoire full of self-regarded, outdated duds. Like Lebowski, the true Dudeist recognizes this and plays with both words and attitudes, trying them all on for size until ultimately stripping them off, jumping in the tub and listening to tape recordings of whale sounds instead.

Now that’s what you call “leisure class.”

(Note: credit for the discovery of the Robert Sale Hill poem as well as some additional aspects of Dude Etymology go to linguist Barry Popik. Papers about the etymology of “Dude” by Popik and colleagues will soon be posted at Dude University.)

* Years ago, Ford Focus came out with a similar ad to the Bud Light one mentioned above, though it looks a little dated compared with the Bud Light one.

That is interesting, man. Not sure how I missed this one before. Shows how much time can change things often into complete opposites. I mean if Dudes today where the same Dudes of yesterday, they would be more like metro-sexuals, not a handle anyone would self apply where I come from, rather then mid day awakening, robe wearing, half and half sniffers – a world of difference with the only real factor being time.

Oscar Wilde invented public relations! He was a true dude . . .