By: Jimmy Brandt

Abstract

Dudeism was inspired by a film released in 1998 named The Big Lebowski, which recounts the adventures of a character called the Dude, the namesake of the religion. The Dude is an example of the (mostly) ideal practitioner of Dudeism, which Dudeists believe has existed throughout the ages, expressed differently by different systems of belief and behavior while retaining an essential Dudeistic spirit.

Dudeism was inspired by a film released in 1998 named The Big Lebowski, which recounts the adventures of a character called the Dude, the namesake of the religion. The Dude is an example of the (mostly) ideal practitioner of Dudeism, which Dudeists believe has existed throughout the ages, expressed differently by different systems of belief and behavior while retaining an essential Dudeistic spirit.

A superficial overlook of this system of belief and behavior finds many similarities to early Taoism, a parallel which Dudeism itself encourages, particularly in regards to the Tao Te Ching. It is also clear that many of Dudeism’s central concepts are inspired or borrowed from said work.

This essay explores the relationship between Dudeism and Taoism through comparison, focusing on the teachings of Tao Te Ching in relation to Dudeist thought and practice. It seeks to establish Dudeism’s religious history as a religion firmly rooted in both a modern motion picture and ancient Eastern thought. The essay concludes that Dudeism has adapted the teachings of the Tao Te Ching for a modern, Western audience through the language and imagery of The Big Lebowski, adding its own twists to ancient concepts.

Contents

1. Introduction p. 1

2. A Note regarding Taoism p. 6

2.1. The Western Perception of Taoism, through Daojia and Daojiao p. 6

3. Whence came Dudeism? p. 8

3.1. Dudeism as a religion p. 10

3.2. Film Analysis of The Big Lebowski p. 12

4. Daojia and Dudeism p. 17

4.1. The Way (Tao) and the Dude Way p. 18

4.2. Inaction (Wu Wei) p. 19

4.3. Yin-yang and the Dude-Undude p. 21

4.4. Dudeitation (Meditation) and Wu Wei p. 23

4.5. The Uncarved Block (P’u) p. 24

4.6. The Dude as a Sage and the Great Dudes of History p. 26

5. Conclusion p. 28

6. Discussion p. 28

Sources p. 30

1. Introduction

Dudeism was organized in its official form (the Church of the Latter-Day Dude) quite recently in 2005, and as such its number of followers are relatively few in comparison to other religions. As of the end 2015, dudeism.com boasted about 300,000 ordained priests around the world, which may or may not account for the majority of devoted dudeists.1

The religion was inspired by a film released in 1998 named The Big Lebowski, which recounts the adventures of a character called the Dude, the namesake of the religion. The Dude is an example of the (mostly) ideal practitioner of Dudeism, which Dudeists mean has existed throughout the ages, expressed differently by different systems of belief and behavior while retaining an essential Dudeistic spirit.

A superficial overlook of this system of belief and behavior finds many similarities to early Taoism, a parallel which Dudeism itself encourages. Lao Tzu is lauded as one of the first Great Dudes in history and the first real book presented by the Church of the Latter-Day Dude was a translation of the Tao Te Ching into Dudeist parlance. It is also clear that many of Dudeism’s central concepts are inspired or borrowed from said work. Beyond this, however, the Church of the Latter-Day Dude offers few specifics on exactly what its Taoist sources might be. The easy-going Dudeist parlance in which most of Dudeism’s literature is written does not exactly maintain an academic tone or any reliable form of source referencing.2

The reason for conducting this study was twofold. Firstly, it is a new religion that was inspired (in its current form) from a motion picture, which is regarded as a source and expression of said religion. It is an unstudied religion with unusual origins and the unstudied part needs to be amended.

Secondly, it is possible that Dudeism represents a Western reinterpretation of Taoist concepts, something which this essay will attempt to ascertain. If so, it might represent an interesting new direction for Taoist studies or entirely new field altogether.

Purpose & Query

The purpose of this study is to discern the relationship between Dudeism and Taoism. To do so, we must first determine what forms of Taoism are relevant and what view Dudeism has of Taoism (and by what perspectives this viewpoint may be have been formed). Thereafter, Dudeism’s religious history to what is inarguably its main source, The Big Lebowski, will be determined, particular in relation to such themes as appear relevant to Dudeism’s connection to Taoism. Finally, a comparison between the relevant elements of Taoism and Dudeism will clarify the latter’s religious history in relation to the former.

The scope of this study is limited to Dudeism and its relation to the Tao Te Ching and The Big Lebowski. The reason for this limitation is to maintain a clear and manageable focus in terms of purpose and query, as well as the process by which these shall be answered. Other influences that appear relevant to Dudeism’s religious history will not be extrapolated upon at any greater length in the essay; however, they will be mentioned in the discussion after the conclusion, along with further commentary regarding specific exclusions.

Query: What is the religious history of Dudeism in relation to its two main sources, the Taoistic text Tao Te Ching and the motion picture The Big Lebowski?

Method

In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in the Study of Religion, Stausberg describes comparison as an unavoidable and often unacknowledged part within the study of religion. The comparative method that will used in this essay follows the outline established by the historian Marc Bloch, quoted below in its succinct and efficacious form:

“…Marc Bloch described comparison as a four-fold project, namely (1) selecting, in one or several different social environments, two or more phenomena that, at first sight, show certain analogies; (2) to describe the lines of their evolution; (3) to observe their similarities and differences; which (4), as far as possible, should be explained (Bloch 1963: 17).” 3

The two phenomena selected here are Dudeism and Taoism, or more specifically, Dudeism and the Tao Te Ching. Since the purpose of this essay is to determine the relationship between Dudeism and Taoism – essentially, to determine Dudeism’s roots – the comparative method was chosen to structure the analysis of the material. Rather than engage in reductionism, however, this study will focus on ascertaining Dudeism’s place in history as a religion that appears both old and new, through its relationship to Taoism.

Comments regarding the Main Sources

The Big Lebowski is a film by the brothers Joel and Ethan Coen, released in 1998. The Coen Brothers had already made themselves known for their genre-bending movies and The Big Lebowski was no exception. At the time of its release, however, the film was not very profitable and received mixed reviews from critics. The cult following it eventually attracted will be explored below in 3: Whence came Dudeism?4

As far as directors go, the Coen Brothers are critically acclaimed but somewhat unconventional. They share several responsibilities such as directing, writing, and editing, but are not generally credited as such. The editor of all Coen Brothers films, for example, is the entirely fictional Rodrick Jaynes, an old and irritable character who does not particularly like their work. Practical jokes such as this can make it somewhat difficult to discern the validity or importance of anything the Coen Brothers have said in their often reluctant interviews. Consequently, this essay will not examine the makers behind The Big Lebowski at any greater length.5

Since it is part of the main focus of this essay, it will be explored in depth below. If one is not familiar with the film, it is advised that one views it before reading this essay. Films are much harder to quote and explain in words, for they rely so heavily on visual and audio components to relay information. If one is unable to view the film, however, a synopsis can be found as an attachment at the end of this essay.

Literature on Dudeism

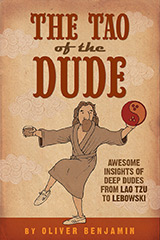

Oliver Benjamin, the Dudely Lama and founder of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, has written two books about Dudeism; The Tao of the Dude and The Abide Guide (the latter co-authored with Dwayne Eutsey). These books explain Dudeism’s ideas, practices and concepts about all manner of things in life, maintaining a light-hearted tone and a quintessential Dudeist parlance. Benjamin has also edited another book, called Lebowski 101:Limber-minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered. It is a collection of assorted essays about The Big Lebowski, many by self-proclaimed Dudeists, which offer different interpretations on the film’s many multifaceted themes. Two essays from this collection will be used extensively in one part of this study, namely “Takin’ It Easy For All Us Sinners: The Dude and Jesus Christ” by Masciotra, D. and “What Makes a Feminist, Mr. Lebowski?” by Gooch, C.

These books should not be viewed as academic works; indeed, the source referencing is notable in its absence and occasionally claims will be made that are less than correct. As books produced by Dudeists to explain Dudeism, however, these books are invaluable for understanding the religion and its history. Even so, when it comes to matters not directly related to The Big Lebowski or specifically Dudeist ideas or interpretations, one should treat the information from these books with a certain wariness.

Literature on Taoism

In the field of Taoism, there is one book that this study has relied on to an outstanding degree: Taoism: Parting the Way, by Holmes Welch. As such, the motivation for choosing this book should be extrapolated. As for the other sources, Fabrizio Pregadio’s and Julia Ching’s works on Taoism have mainly been used to narrow down the field of study to the Tao Te Ching, while Arthur Waley translation has, of course, been used to read it and better understand its meaning.

Holmes Welch (1924-1981) was active within the fields of Buddhism and Taoism. He studied and researched both religions at various points in his life and appears to have held the respect of his contemporary peers.6

His first major work, Taoism: The Parting of the Way, presents a study of Lao Tzu and his work, the Tao Te Ching, as well as an overview of subsequent Taoist history. The reasons as to why Welch’s interesting but now somewhat dated study of Taoism was chosen as one of the main sources for this essay are threefold.

Firstly, it is quoted multiple times in The Tao of the Dude,7 which in and of itself may be insignificant; The Tao of the Dude contains a vast collection of quotes ranging from renowned philosophers to cartoon characters. Its mention is notable in relation to the content of the quotes and the chapters in which they appear. The assumption that some of Dudeism’s understanding of Taoism (specifically the message of the Tao Te Ching) may have been formed by Welch’s work warranted further investigation. It should be noted that it was not on this merit that Welch’s book was eventually chosen as an integral part of this study and that there appears to be no concrete relationship between Dudeism and Holmes Welch other than these quotes. If Dudeism’s understanding of the Taoism was significantly shaped by Taoism: The Parting of the Way is neither stated explicitly nor implied in any Dudeist literature.

Secondly, in correlation to a general overview of Taoism (aided by Pregadio and Waley), it became clear that Dudeism had focused mainly, if not solely, on the very first Taoists, specifically the Tao Te Ching. This rendered the greatest weakness of Taoism: The Parting of the Way partially irrelevant, namely its dated division between philosophical and religious Taoism, as well as the occasionally dismissive tone towards the latter. This dated division will be expounded on below in the section below, 2.1: The Western Perception of Taoism.

Thirdly, Welch’s study of the Tao Te Ching is comprehensive and detailed, thus providing a useful aid in elucidating the meaning of the oftentimes mystical and difficult text. This was essential for analyzing Dudeism’s ties with the Tao Te Ching, for it provided context and clarification for the central concepts of the latter.

Glossary

-

Lao Tzu/Laozi – “Old Master”. The author of the Tao Te Ching is often viewed as an important source and figure within Taoism (within the Taoist pantheon he appears as a sort of god). Who the historical Lao Tzu actually was is uncertain and debated. Most seem to agree that he lived during a turbulent time of war in between the quarrelling states of China, sometime around 300-400 B.C.

-

Tao Te Ching/Daodejing – “The Way and Its Power”. The short book written by Lao Tzu before he wandered west. Its tone is mystical and its meaning is elusive as it attempts to elucidate upon the Tao and how to best live in accordance with this unnameable way. In doing so, the book also touches upon politics and issues advice for how to best govern a kingdom or empire.

-

Tao/Dao – “The Way”. An impersonal, Supreme State or Force of the universe. The primary subject matter of the Tao Te Ching, but also a phrase in common usage throughout all Chinese culture and religion. The Tao of which Lao Tzu speaks need not even be the Tao which concerns Taoism, as we shall see more below.

-

Wu wei – “Actionless action” or “Inaction”. See more below.

-

P’u – “The Uncarved Block”. See more below.

-

Sheng jen – “The Sage”. See more below.

-

Yin-yang – See more below.

-

Daojia/Tao chia – “Lineage(s) of the Way” or “The Taoist School”. See more below.

-

Daojiao/Tao chiao – “Teaching(s) of the Way” or “The Taoist Sect”. See more below.

-

The Dude – Jeffrey Lebowski, a fictional character in the film The Big Lebowski. The main inspiration and the ideal “Sage” of Dudeism. See more below.

-

The Dude Way – The Tao, as interpreted by Dudeism. See more below.

-

The Dude and the un-Dude – Yin-yang (Dude=yin; un-Dude=yang). What is Dude is, of course, generally represented in the nature and behavior of the Dude. What is un- Dude is often the nature and behavior of the Dude’s friend and counterpart, Walter Sobchak. See more below.

-

Great Dude(s) – Various personages of any gender, fictional or historical, who clearly represented the Dude (i.e. Dude-like ideas and behavior) and in some way followed the Dude Way (as interpreted by Dudeism). See more below.

2. A Note regarding Taoism

Taoism may not be a familiar religion even among students and experts of the religious sciences and although it is central to this study, it is not its main focus. As such, this essay may not give the reader a complete or in-depth view of Taoism, focusing instead on such aspects of Taoism as has been found pertinent to the essay’s purpose. These will be explained throughout the text when relevant, often in comparison to Dudeism, since elucidating the connection between the two religions is the purpose of this inquiry.

2.1. The Western Perception of Taoism, through Daojia and Daojiao

The Chinese Taoists themselves have in the past made a (not always clear) distinction within Taoism, but this partition appears to not have been of any greater concern to its practitioners. The two terms, Daojia/Tao chia and Daojiao/Tao chiao, respectively translated as Lineage(s) of the Way and Teaching(s) of the Way, has been used by Taoists “…interchangeably to denote what we call ‘Taoism’, and sometimes separately to distinguish the teachings of the Daode jing (and a few other works including the Zhuangzi) from ‘all the rest.’”8

Instead, one can say that it has mostly been of interest to the Western scholars, who early on were keen to separate the Tao Te Ching and those few other works from “…those whom we can only regard as representatives of quaint, but moribund superstition”.9 This Western perspective of “Philosophical Taoism” and “Religious Taoism” appears to be a particular annoyance to contemporary Taoist scholars, whose focus seems to have shifted from the nascence of Taoism to the following 2000 years of beautiful tradition, as the Dudeists would say. Pregadio, in the foreword to his massive encyclopedia, puts it as such:

“Whereas in earlier times Taoism was deemed by Western scholars to be nothing but a philosophy, and any involvement in the domain of religion was either denied or classified as “superstition,” in the last few decades Taoist scholarship has shifted to the opposite extreme, sometimes even going so far as to deny any foundational role to a work like the Daode jing (the latter opinion has been held only by a few scholars working primarily in the broader field of Chinese religion rather than Taoism).”10

Since the purpose of this essay is mainly to discern the religious history of Dudeism, no particular stance will be assumed on what may or may not be Taoism. Daojia and Daojiao do, however, provide a useful point of departure in determining what kind of Taoism has informed the Church of the Latter-Day Dude.

Daojia denotes the works of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, as well as a few partisans who could be said to follow the same philosophy. This philosophy and its concepts will be expounded upon below, for underneath its venerable veneer it presents clear parallels to the easy-going gospel of Dudeism. This is perhaps not so surprising, since Dudeism regards the Tao Te Ching as one of the earliest examples of Dudeism in recorded history.

It should be noted that Daojia was by no means a formal “school”; according to Pregadio’s Encyclopedia of Taoism, syncretism combined the earlier scholars into one tradition.11

To fully summarize what Daojiao denotes would require an essay (and more) unto itself, for as Pregadio puts it, this more or less encompass “all the rest”. Apart from the works of Daojia, which are included in Daojiao’s vast canon consisting of over a thousand volumes, there are also concepts and practices concerning inner and outer gods, immortals, alchemy and rituals for both exorcism and healing.12

Welch means that Daojia includes “…all those groups that have taken immortality as their goal – alchemists, hygienists, magicians, eclectics, and in particular, the members of the Taoist church.”13 The Taoist church, as Welch summarizes it, consists of:

“… the science of alchemy; maritime expeditions in search of the Isles of the Blest; an indigenous Chinese form of yoga; a cult of wine and poetry; collective sexual orgies; church armies defending a theocratic state; revolutionary secret societies; and the philosophy of Lao Tzu.”14

This overview of Daojia and Daojiao is sufficient to determine what has not been passed onto Dudeism. According to Pregadio, Daojiao is mainly focused on establishing a relationship with the sacred.15 The sacredness of Daojiao, be it alchemy, immortality or various deities, is nowhere to be found in the profanely irreverent and intentionally “underachieving” religion of Dudeism. In the words of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude itself: “Probably the earliest form of Dudeism was the original form of Chinese Taoism, before it went all weird with magic tricks and body fluids.”16

As such, focus will be placed on a comparison between Daojia and Dudeism, especially to see how closely the different interpretations of the Tao Te Ching (also translated into Dudeist parlance as The Dude De Ching) are related. In the interest of time and space, the Chuang Tzu, will be not studied and compared to Dudeism in this essay. Focus will instead be placed on the Tao Te Ching and The Big Lebowski.

3. Whence came Dudeism?

Dudeism, in the form of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, began in the year of 2005, when its founder – Oliver Benjamin, the Dudely Llama – watched The Big Lebowski in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and had a transformative experience. Benjamin, born in 1968, was and remains a freelance journalist and author. He appears to have had some objections to the pressures and expected lifestyle of modern day society even before founding modern Dudeism. In an interview with CNN, he states:

“I grew up in the 1980s, which was a very ambitious and materialistic time – the era of the Yuppies. Even as a youth, I found it frightening and false. The reason I embarked on a 10-year backpacking journey was so I could avoid being brainwashed by the machine of industry, and find the space and freedom to indulge my imagination.”17

While Benjamin may have officially founded Dudeism in the form of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, it can be said to previously have existed in two forms. The first form, as argued by modern Dudeists, is that the core philosophy of Dudeism has existed throughout the ages, expressed differently by different systems of belief and behavior while retaining an essential Dudeistic spirit. As expressed on their webpage:

“The idea is this: Life is short and complicated and nobody knows what to do about it. So don’t do anything about it. Just take it easy, man. Stop worrying so much whether you’ll make it into the finals. Kick back with some friends and some oat soda and whether you roll strikes or gutters, do your best to be true to yourself and others – that is to say, abide.”18

The second pre-existing form of Dudeism would be as the cult following that The Big Lebowski had attracted. The fans of the film may not be cultists in the religious sense, but the internal language (based off quotes and the particular parlance of the film) coupled with the events to celebrate the film and its characters certainly established The Big Lebowski’s fandom as a distinct community.

The biggest of these events is Lebowskifest. According to lebowskifest.com, since the first Lebowski Fest in Louisville, Kentucky, in the year of 2002, the festival has been held in 30 cities both in and outside of the U.S.19 Actors and others involved with the film have attended. As for the festival itself:

“Lebowski Fest is typically split into two days starting with the Movie Party which usually includes a band or two and a screening of The Big Lebowski. The next day is the Bowling Party which includes unlimited bowling, costume, trivia and other contests.”20

Dudeism, one might say, thus comes from these two things: the fan following of The Big Lebowski and the Dudeistic idea of an ahistorical, persistent philosophy. But what religious ancestry has The Big Lebowski and this philosophy? The Dudeists connect it at its furthermost historical end to the Tao Te Ching and the relationship between the two shall be explored below. First, however, due attention will be given to explaining modern Dudeism and examining The Big Lebowski and those of its themes that are directly relevant to this study.

3.1. Dudeism as a religion

In the Take It Easy Manifesto of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, an effort is made to extrapolate the ethos of Dudeism. This is done in a comparison to Buddhism, which remains included below for greater clarity.

“From what is Buddhism trying to liberate us? Suffering To what state of being is Buddhism trying to bring us? Nirvana By what means does Buddhism attempt do this? The Noble Eightfold Path. Isn’t that fucking interesting, man?

Now let’s apply it to Dudeism:

From what is Dudeism trying to liberate us? Thinking that’s too uptight. To what state of being is Dudeism trying to bring us: Just taking it easy, man. By what means does Dudeism attempt do this? Abiding.”21

The Take It Easy Manifesto goes on to apply “the seven dimension of religion identified by one Ninian Smart”22 to Dudeism. Since it would be difficult to summarize their points more succinctly (but perhaps not more academically) than the authors of the Manifesto, the text is quoted in full below. This also provides an excellent example of Dudeism’s idiosyncratic parlance, based so heavily on references to the mode of speech or direct quotes from The Big Lebowski (as well as the occasional pun), which appears to integral to Dudeism as a mean of self-expression. It should be read with this in mind, lest one misinterpret the text as purely facetious.

- Doctrinal (the systematic formulation of religious teachings in an intellectually coherent form): Like Zen, Dudeism isn’t into the whole doctrinal thing; we prefer direct experience of takin’er easy, and often contemplate two indiscernible Coens to achieve that modest task. Perhaps the closest Dudeists come to having a systematic formulation of our religious teachings is: “Sometimes you eat the bear, and, well, sometimes the bear, he eats you.” Is that some sort of Eastern thing? Far from it, Dude.

- Doctrinal (the systematic formulation of religious teachings in an intellectually coherent form): Like Zen, Dudeism isn’t into the whole doctrinal thing; we prefer direct experience of takin’er easy, and often contemplate two indiscernible Coens to achieve that modest task. Perhaps the closest Dudeists come to having a systematic formulation of our religious teachings is: “Sometimes you eat the bear, and, well, sometimes the bear, he eats you.” Is that some sort of Eastern thing? Far from it, Dude.

- Ritual (forms and orders of ceremonies): Dudeists are also not into the whole ritual thing, but there are some things we do for recreation that bring us together, like bowling, driving around, the occasional acid flashback, listening to Creedence. Some Dudeists are Shomer Shabbos, and that’s cool.

- Ethics (rules about human behavior): Although this isn’t ‘Nam, there aren’t many behavioral rules in Dudeism, either. However, we do recognize that we may enter a world of pain whenever we go over the line and we are forever cognizant of what can happen when we fuck a stranger in the ass.

- Experiential (the core defining personal experience): Abiding and takin’er easy.

- Myth (the stories that work on several levels and offer a fairly complete and systematic interpretation of the universe and humanity’s place in it): The Big Lebowski is our founding myth; just as the Christian Gospels, based on the Jesus of history, provide a portrait of the mythical Christ of faith who “died for all us sinners,” the film, based on the Dude of history (Jeff Dowd), presents the mythical Dude of film (Jeff Bridges) who “takes it easy for all us sinners.”

- Material (ordinary objects or places that symbolize or manifest the sacred or supernatural): That rug really tied the room together, did it not?

- Social (a system shared and attitudes practiced by a group. Often rules for identifying community membership and participation): Racially we’re pretty cool and open to pretty much everyone… pacifists, veterans, surfers, fucking lady friends, vaginal artists, video artists with cleft assholes, dancing landlords, doctors who are good men and thorough, enigmatic strangers, brother shamuses… And proud we are of all of them.

Those we consider very un-Dude include: Rug-pissers, brats, nihilists, Nazis, human paraquats, pederasts, pornographers, fucking fascists, reactionaries, and angry cab drivers. Friends like these, huh, Gary?23

To better understand the picture that the above text seeks to paint of Dudeism, one must understand the heart and source of its means of expression, i.e. The Big Lebowski. A synopsis can be found as an attachment at the end of this essay. To conclude this section on Dudeism as a religion, it must be made abundantly clear that even its organized form, as the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, Dudeism is a decidedly disorganized religion, which makes it difficult to grasp. The reason for this lack of structure and authority may be directly related to its roots in The Big Lebowski, which will be analyzed here below.

3.2. Film Analysis of The Big Lebowski

The Big Lebowski is a multifaceted movie with many themes. Not all these themes will be explored here below, for while matters such as the film’s take on the genre of neo-noir may be interesting, it is ultimately not pertinent to the purpose and query of this essay. Furthermore, to make a full analysis of the movie would be to merely echo experts and critics with far more experience in the field of film studies. What concerns us here are matters of religion and aspects of the film that has influenced and helped shape Dudeism.

This analysis will as such focus on two things: religious themes in the film and the emasculation of the American male. This will aid us in understanding what has had the most evident and perceptible role in shaping Dudeism as a religion.

Religious Themes in The Big Lebowski

The Big Lebowski is rife with religious motifs, both the inevitable by-products of being made in a culture rooted in Judeo-Christian thought (“What in God’s holy name are you blathering on about?”) as well as deliberate symbolism. The presence of various major world religions will be determined and evaluated, then separately considered in relation to Dudeism.

Judaism has a very clear representative in Walter Sobchak, the angry Vietnam veteran who converted to Judaism from his native Polish Catholicism when he married his ex-wife. He values his adopted Judaism highly, to an almost fanatical degree, seemingly as a way to remain close to his ex-wife. This is entirely in line with his character; Walter is someone who lives in the past, be it the Vietnam War or his failed marriage. When the Dude questions the authenticity of his adopted religion near the end of the film, Walter responds, “Three thousand years of beautiful tradition, from Moses to Sandy Koufax… YOU’RE GODDAMN RIGHT I’M LIVIN’ IN THE FUCKIN’ PAST!”24

Walter, in short, clings to tradition. This is something that the Dude derides, adding yet another parallel to a robed, bearded, long-haired and sandal-shod pacifist. The observation that the Dude might be a modern day Christ figure is hardly new or unique, but it becomes interesting when compared to the appearance of another Jesus.

Jesus Quintana is an overtly sexual bowler with a criminal record as a pederast. This exceptionally sacrilegious character appears only briefly in the film as a member of an opposing bowling team and his few lines of dialogue serve only to insult the Dude and Walter. In a very Christian manner, the Dude turns the other cheek and responds with the now famous line, “Yeah, well, you know, that’s just, like, uh, your opinion, man.”25

The Christian themes of Jesus Quintana and the Dude are contradictive. The Dude, as previously mentioned, can easily be likened to a Christ-figure. In the collection of essays called Lebowski 101: Limber-minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered, a thoroughly Dudeist work, an essayist by the name of David Masciotra draws several parallels between the lives of Jesus Christ and the Dude.

Both were pacifistic political activists and even though the Dude has left that life behind, he still refuses to behave deferentially towards authority. As Masciotra notes, an interesting parallel can be drawn between the Big Lebowski as the Jewish Pharisees and the Sheriff of Malibu as Pontius Pilate. When the Dude and Jesus are insulted or accused of a crime, in each respective circumstance, both respond in a non-aggressive, non-deferential manner.26

Unlike most in their environment, both Jesus and the Dude willingly lead lives of poverty; the former took an explicit vow, while the latter rejects capitalism, employment and materialistic achievement for a more humble life. Both show little concern for the future; worrying about what they shall eat or how they are going to pay their rent would only cause undue stress.27

Finally, Masciotra argues that American Christianity has lost its way, to a point where the Dude is a better representative of Christian living than the average American. Masciotra states that what Jesus preached, such as “…love and forgiveness of enemies, hospitality to strangers, and compassion to the poor…” is not a message reflected in American society. The U.S. has the largest and most powerful military on earth and Masciotra means that it favors the rich over the poor in addition to a growing hostility towards immigrants. Furthermore, Masciotra notes that “…the American government carries out all of their atrocities via the mandate, through either apathy or lustful excitement, of its people.”28

So what of Jesus Quintana? If the Dude can be said to practice the teachings of Gospels more accurately than self-proclaimed Christians, then Quintana might be said to represent this hypocrisy, especially that of a traditional Christian establishment such as the Catholic Church. Jesus Quintana is clearly meant to be of Latin descent; disregarding his name and appearance, his leitmotif is a Spanish cover of “Hotel California” and he speaks with a strong accent, emphasized by the phrase “Dios Mio.” In addition to a purple jumpsuit (purple being a color associated with Catholic Bishops), Quintana’s dress includes ostentatious gold rings set with jewels. This paints a very negative and prejudiced portrait of Catholicism: a Catholic character (evinced by the name Jesus, the Latin descent, and the purple jumpsuit), who is a known pederast (prejudice towards priests of the Catholic Church may involve pedophilia) and who ornaments himself with ostentatious jewellery (as opposed to the Gospels’ message of poverty). Assuming Masciotra is correct about American Christianity having lost its way, then Jesus Quintana may represent how Christianity as a whole has lost its way. The Dude becomes the counterpoint to the established, institutionalized religion.

This is not altogether surprising, however, or out of line with the idea of the Dude as a modern day Jesus. The Dude staunchly opposes tradition for tradition sake. The Dude forces Walter to break the law of rest on the Sabbath and derides his commitment to Jewish tradition. The Catholic Church is a major representative of tradition within Christianity; to juxtapose the Dude with a caricature of Catholicism thus enforces his character as being anti-establishment and opposed to tradition. The prejudiced and offensive portrait of Catholicism is not entirely out of place in the film, considering the depiction of Walter’s Judaism.

Islam is an ever-present undercurrent throughout the film, even though it only makes a direct visual appearance in one the Dude’s hallucinatory dream sequences, in the form of Saddam Hussein. The Gulf War is the backdrop of the entire film; it is one of the very first things referred to in the opening lines by the narrator. In its implied form of Iraq and Saddam Hussein, Islam comes to play its usual role in Western media and storytelling: “the Other.” It is not central to the plot of the film, other than as an “unworthy” adversary for Walter, a precursory neo-conservative whom one might describe as a walking metaphor for Bush the Elder’s administration.29

Buddhism, along with Taoism, only has an implied presence in the film as the religion of the Dude. It is clear the Dude is into “some kind of Eastern stuff”, as evinced through his tai-chi, meditation, and various snippets of dialogue. He does not display, however, the discipline inherent to many forms of Buddhism. Furthermore, he consistently contradicts many of the Buddha’s teachings: he consumes drugs in the form of alcohol and marijuana, he lies through his teeth at several points throughout the film, and finally, although misguided, it is clear that he has attachment to certain material things, such as his rug, his car or his Creedence mix tapes.

The Dude is by no means an ideal practitioner of any major form of Buddhism or Taoism; he is inherently flawed. However, he may represent a Western adaptation of many Far Eastern concepts, which he practices in his own peculiar way. As such, while Buddhism and Taoism may be important to the Dude, it is not necessarily essential to the film, especially compared to Judeo-Christian thought or 20th-century American culture.

This is interesting in regards to Dudeism as a Western movement inspired by Eastern thought: its means of expression is thoroughly Western, for it is in and of the West. After all, the main intended audience of the film would be rooted in Western thought and praxis: much the same can be said of the intended audience of Dudeism. Much like the film, it is firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian thought, even though it rejects major parts of it (be it God, salvation, or tradition) for an Eastern ideal portrayed by the Dude. The religious themes in the film deconstruct Western religion and, subversively, presents as Western reinterpretation of Eastern religion as an alternative.

The Emasculation of the American Male

Feminism runs parallel with the theme of the emasculation of the American Male throughout the film. The former is clearly represented by Maude, a self-identified feminist; she both represents a feminist as a character and ideas of feminism as a theme. This will be discussed briefly, for it is relevant, albeit perhaps not central, to the emasculation of the American Male and its significance to Dudeism.

Maude Lebowski is a major character in The Big Lebowski and what she symbolizes has been a much debated topic. In the collection of essays called Lebowski 101: Limber-minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered, a thoroughly Dudeist work, an essayist by the name of Cate Gooch argues against the dismissal of Maude as a “stereotypical ‘Radical Feminist.’”30 According to Gooch, Maude represents an interesting middle-ground between Third Wave Feminism and Post-feminism, in that she does not seem to be concerned with the generalized issues of the former, while staunchly refuting the latter by clearly calling out the enduring gender inequality and double-standards in today’s society.31 Maude is a powerful character and certainly capable of exerting that power over her environment. She is consistently portrayed as superior to many of the other men in the film, such as her father, her employees, and the Dude himself.

As such, her interactions with the Dude becomes interesting, for he does not seem to mind this at all. The Dude has no objections to a woman being equally or more powerful than him and although Maude’s demeanor can be seen as confrontational in their first scene, Gooch argues that this was merely as test for the Dude to pass. In much the same way that the Dude was the man for his time and place, Gooch means that Maude becomes the woman for her time and place: a middle-ground between Third Wave Feminism and Post-feminism, powerful and capable in her own right.32

Understanding Maude’s role is essential for understanding the consistent theme of the emasculation of the American Male that runs throughout the film. It should be noted that this emasculation is not to be viewed as negative; rather, it deconstructs American masculinity and poses the question what remains once the shroud has been pulled aside. Maude is relevant, for the implied culmination of her story arch – becoming pregnant and having a child, an all too common trope for women in film – serves to illustrate the redundancy of men as nothing more than a pair of testicles.

Maude’s goal, stereotypical though it may seem, actually opposes traditional gender roles. To Maude, the Dude ultimately functions as a sperm bank; a necessary factor for pregnancy. She does not intend to settle down and form a family with the Dude as a supremely miscast patriarch. The reason she is having a child is entirely for her own sake, which becomes a strong self-expression of her own female power. She does not have to abandon a career to become a mother and her choice to enter that role will in no way be controlled by the father of her child or, for that matter, her own father.

Maude’s view of the Dude is one that he appears to possess himself. When the Big Lebowski pompously ponders what makes a man, the Dude’s straightforward reply is “a pair of testicles.” The idea that a man is nothing more than a pair of testicles contradicts the myth of what the American Male should be: something more, an ideal usually depicted by a muscle-bound, red-blooded action hero of the sort that appears in Hollywood productions every year, often juxtaposed to a woman in the role as a damsel in distress and a love interest. In the opening lines of the film, the narrating Stranger is careful to mention that the Dude is not a hero, but merely the man for his time. In short, the Dude is not the typical masculine hero. His entire masculinity is confined to possessing a pair of testicles.

Dudeism has been sly enough to pick up on this theme and it seems to be thoroughly incorporated into the religion, something which will be discussed in greater detail below in comparison to Yin-yang. In regards to the film and the testicles, however, their reasoning is rather simple. To paraphrase Oliver Benjamin: due to increased equality in today’s society, it has become apparent that women are just as capable as men at any task. Consequently, the male role of a protector or a hero is no longer necessary and there is no longer anything special to being a man other than a pair of testicles.33

The men in The Big Lebowski try to compensate for their redundancy in different ways, often by attempting to recapture former glory days of either war, wealth, or sexuality, which generally end in some form of failure. There are two men, however, who do not strive towards masculinity: the Dude and Donny. The latter is as meek as to be self-annihilating, desperately fighting for a chance to say something even as he chokes to death in Walter’s vainglorious shadow. The Dude is merely passive, at a state of absolute rest: he dropped out of society and any role of greater responsibility. He was the man for his time and place in that he appears to have had no need or desire of ever being a man beyond the possession of his testicles. The Dude is content to simply be the Dude.34

4. Daojia and Dudeism

The Tao of Lao Tzu and the Tao of the Dude

There appears to be many similarities between the Tao of Lao Tzu and the Tao of the Dude. With the help Holmes Welch’s commentary on the Tao Te Ching and various books on Dudeism, we shall try to discern the nature of these similarities. Simultaneously, we will also examine another key focus of Dudeism – the Dude himself. This section will illustrate that the Dude and The Big Lebowski appear to embody many of the concepts that Lao Tzu presents in the Tao Te Ching. Many of these concepts have thus helped shape the very heart of what is called Dudeism.

4.1. The Way (Tao) and the Dude Way

The Tao Te Ching opens with a line that is usually translated, with some variation, as “The Tao that can be named is not the Tao”.35 In essence, this means that trying to explain the Tao through words is hopeless. Consequently, what we know of the Tao is delivered in a mostly apophatic format, i.e. in terms of negation.

The Dude Way is not easily defined in words either (especially since the consistency of the phrase appears to vary in relation to its use as a situational pun contra permanent descriptor). Looking at The Big Lebowski, the Dude never clarifies his philosophy in words beyond proclaiming himself a pacifist and misquoting Cicero as Lenin. Dudeists themselves admit that “… at first glance, the Dude seems to have no lucid political philosophy… nothing beyond pacifism, anyway.”36 It is to his actions that Dudeism has looked for inspiration – the Dude in The Big Lebowski is the embodiment of the Dude Way.37

To define the Dude Way by other words, one could say that it is “the natural way of things”. According to The Abide Guide, humans forgot the Dude Way when “… their thinking about the purpose of life became too uptight.” When society arose with its rules and demands, its notions of success and wealth, The Abide Guide states that humans who were simply being became overachieving humans.38

Welch attempts to make a distinction between what he perceives as the Manifested Tao of the universe and the aspect of Tao that we cannot define, the Nameless Something Else of Non-being from whence everything came.39 He tries to compare Lao Tzu’s descriptions of the Tao with other mystical experience, to see “… how Lao Tzu supported his claims to valid trance experience, how he knew that it was anything more than his imagination.”40 After many examples, he arrives at no conclusive answer, and states that it is beyond our ability to do so.

Dudeism makes no greater claim on the metaphysical realm, focusing more on the practical aspect of how to enact their teachings than contemplating their abstract potentials. The Dude Way is described in a meandering manner as the source of the universe, but it is no metaphysical, higher power to be beseeched and no font of miracles.41 Welch says the same about Lao Tzu’s Tao: “Tao is impersonal, ‘unkind’, and beyond the reach of prayer. It is real, but no more real than the universe it governs.”42 The Dude Way, much like the Tao, is a name for the state of being which, when one lives in accord with it, ensures well-being.43

According to The Tao of the Dude, practicing inaction is at the heart of the Dude Way. The life of the Dude is one blissfully free from worry precisely because it is an uncomplicated, “empty” life devoid of strivings for societal gain or materialism.44 What inaction – wu wei – and its practice means will be explained below.

4.2. Inaction (Wu Wei) and the Dude Way

Wu wei does not exactly mean “do nothing” – it is usually translated as “actionless action”. According to Welch, what Lao Tzu means is that one must act without aggression:

“Wu wei does not mean to avoid all action, but rather all hostile, aggressive action. Many kinds of action are innocent. Eating and drinking, making love, ploughing a wheat-field, running a lathe – these may be aggressive acts, but generally they are not. Conversely, acts which are generally aggressive, like the use of military force, may be committed with such an attitude that they perfectly exemplify wu wei. The Taoist understands the Law of Aggression and the indirect ways that it can operate. He knows that virtuousness or non-conformity can be as aggressive as insults or silence. He knows that even to be non-aggressive can be aggression, if by one’s non-aggressiveness one makes others feel inferior. It is to make another person feel inferior that is the essence of aggression.”45

One of the first subjects expounded upon in the book The Tao of the Dude is Taoism and “Woo Wee”, wherein the author gleefully makes note of a curious detail regarding the desecration of the Dude’s rug (a thug named Woo wees on the rug) while also advocating the practice of wu wei in that very particular Dudeist parlance.46 “This aggression will not stand”, originally uttered by the Dude in the film (and before that by George Bush Senior), is recycled unrepentantly within the Dudeist scriptures as is of course the concept of “Abide” or rather “Abiding”. Indeed, what is abiding if not actionless action? In the Dude de Ching, however, “to abide” appears to be their translation of pity, love or compassion, i.e. the first of the Three Treasures mentioned in Chapter 67.47 This does not seem to be an entirely consistent expression, like so many things in Dudeism.

In The Tao of the Dude, on the matter of practicing wu wei, Benjamin notes that “… even a skilled Taoist like the Dude repeatedly got it wrong.”48 Indeed, in the film the Dude often panics or gets riled up by Walter. Even so, he is usually able to quickly bounce back from these traumatic or stressful events that most of us would worry about for days, usually through what Dudeists term dudeitation, which will be expounded upon below.

Water is a common metaphor or likeness used in the Tao Te Ching as an element one should emulate. It is praised for being low and yielding, thus enabling it to conquer the high and hard.49 Dudeism embraces this idea and as such one might call it the religion or philosophy of going with the flow. The Dude’s goal in the film is merely to re-establish status quo – i.e. get his rug back – and in The Tao of the Dude this is compared to “water seeking its level”, an expression that echoes the Tao Te Ching.50 Indeed, the film’s plot might not even have taken place if it had not been for the aggressive, self-righteous Walter urging the Dude to seek repairs from the Big Lebowski. In the end, he does not even get his rug back, which Benjamin describes as “…the price he pays for going against the flow.”51

It can be fairly conclusively stated that Dudeism adopted Lao Tzu’s wu wei without much alteration, except a minor coat of paint and translation into Dudeist parlance. Indeed, Benjamin claims that “His [the Dude’s] story is a perfect illustration of the mechanics of wu wei, or a as some of us Dudeists like to call it, ‘Dude Way’.”52

4.3. Yin-yang and Dude-Undude

Both Lao Tzu’s wu wei and Dudeism wholehearted acceptance of the concept is related to yin-yang and Dudeism’s aversion to the traditional American male gender role, as discussed above in the film analysis. Yin-yang – The Female-Male – commonly depicted as a black and white fish entwined in a circle, is viewed by many as a symbol of Taoism. The two forces are one; they complement each other and exist within each other; yin is dark and passive, yang is bright and active. Lao Tzu focuses on how one should emulate the yin, the female, which practices wu wei as opposed to yang’s male aggression. As Welch puts it: “…the symbol of the Female, who, like the Valley, is yin, the passive receiver of yang; who conquers the male by attraction rather than force; and who without action causes the male to act.”53

That Lao Tzu so greatly emphasizes that one should cleave to the female throughout the Tao Te Ching54, thus emulating the passive, yielding nature of yin55, becomes a prominent theme in Dudeism. It is clearly connected to the emasculation of the American male as nothing more than a pair of testicles. One could posit that to fill the void left by the absence of masculine identity, Dudeism followed the Dude’s example and embraced the way of yin as a practice to emulate.

In Dudeism, the concept of yin-yang is relayed through the relationship of the Dude and Walter, i.e. the Dude and the Undude (sometimes also spelled Un-Dude). Throughout the course of film, Walter excellently portrays aggression and hostility, speaking of worthy adversaries and drawing his weapon to enforce his perception of the rules. It is only through his urging, or as The Tao of the Dude puts it, “Walter’s aggressively Confucian ‘giving a shit about the rules’”,56 that the misadventure of The Big Lebowski even takes place. It never even occurred to the Dude to seek recompense for his rug, even though he lamented its loss.57

In addition to his unchecked aggression, Walter almost always acts in an authoritarian, dominant way. The main exception is after having scattered Donny’s ashes, when he softly asks the Dude for forgiveness and hugs him. In short, as a representation of the Undude, Walter acts with aggression and bombastic pride, trying to take control of every situation he finds himself in and through intimidation or violence enforce his will.

In the final chapter of Taoism: The Parting of the Way, Welch has a hypothetical Lao Tzu comment on the state of present-day U.S.A. (in 1957). To give Taoistic context to Walter’s behavior, we turn Welch’s hypothetical Lao Tzu’s advice and commentary:

“’Your foreign troubles are grave indeed. Soon they will be graver. That is because your statesmen want America to play the role of the male. They would have America, like the stag, rush forward through danger, expecting that because it is strong and handsome all the other nations will follow. But nations are not a herd of deer, and leadership is not won by physique alone.”58

This excellently describes Walter’s ethos and behavior. The Tao of the Dude draws a clear parallel between the aggressive demeanor of Walter Sobchak and American foreign policy. Walter is a neo-conservative who preceded the neo-conservatism of the early 21th-century, seeking a worthy adversary to righteously fight and conquer. Despite his prowess in combat, Walter rarely wins: when vandalizing what he believes to be Larry Sellers’ car, he provokes its real owner who assaults the Dude’s vehicle; in the fight with the nihilists, he emerges victorious but Donny loses his life from a coincidental heart attack. A running theme in The Big Lebowski is the presence of the Gulf War in the background, as mentioned above in the film analysis. The Tao of the Dude means that the military situation the U.S. faced and still faces in the Middle-East during the early 21th-century to no small extent is a consequence of that war.59

The Tao of the Dude also means that The Big Lebowski presents Walter’s relationship to his ex-wife and Judaism as a parallel to American foreign policy:

“First of all, when The Big Lebowski was released in 1998 there was little indication that America would suffer any serious backlash from the first Gulf War, nor an unflinchingly, religiously sentimental support for Israel (lampooned in Walter’s clinging to the adopted Orthodox Judaism of his ex-wife Cynthia).”60

We have at great length explored the character of Walter and his representation of the Undude as an aggressive, dominant force. What is the Dude and how does it relate to Dudeism embracing the emasculation of the American male? Welch’s commentary on how he believes Lao Tzu would view American society provides context:

“For him [Lao Tzu] improvement of character means better suiting man to not fighting wars. A noble man can fight wars: a brave man can fight them: a strong man can fight them. Our ideals of character resemble those by which primitive societies raised their children to be hunters, warriors, and kings. In raising our children to become warriors and kings at school, in the factory, on the political platform, and in the bomber cockpit, we teach them strength and courage. We excite their ambition, giving them – if we can – an indomitable will to get to the top. We show them that they must always be ready to sacrifice themselves or others for the good of the tribe, for a moral principle, or for a difference of opinion. The result is inevitable. They cannot leave one another at peace. Kings will have kingdoms and warriors wars.”61

The Dude is a pacifist who asks very little of life. Through his practice of wu wei, he cleaves closer to yin and its passivity. When insulted by the Jesus, the Dude merely replies “Well, yeah, that’s just, like, uh, your opinion, man”. He does not strive or seek to take control – he goes with the flow, an antithesis of aggression and ambition. The Big Lebowski represents, for the Dude, an unusual, very stressful chapter of his life. Occasionally he acts very “un-Dude”, as Dudeists duly acknowledge, such as when he panics about failing the ransom handoff or allows himself to get riled up by Walter.62 Despite this, the Dude can be said to never try to take control of or attempt to dominate a situation. Welch’s interpretation of wu wei and its objection to aggression is that “It is to make another person feel inferior that is the essence of aggression.”63 Whereas Walter revels in oppressing Donny and his general environment by verbal or physical abuse, the Dude does not. It does not even appear to entail much of an effort; in fact, given the Dude’s laziness, it only natural that it does not. If, as Welch says, “Kings will have kingdoms and warriors wars,”64 then the Dude will have peace and nothing more. Not even a rug.

4.4. Dudeitation (Meditation) and Wu Wei

Dudeism is rife with puns and wordplay attempting to reference The Big Lebowski in any manner, way, shape or form. So of course their version of meditation would be called Dudeitation. Hidden behind the groan-inducing pun, however, there is a relevant connection to Taoism.

Dudeitation, like most elements of Dudeism, is firmly grounded in the practice of wu wei. According to The Abide Guide, dudeitation entails making yourself comfortable (in the bathtub, lying on a rug, doing tai chi with a White Russian in hand) and letting your mind go limber. There is no required amount of time one must dudeitate, but it is recommended that one practice often. It is supposed to be an antidote to the stress and demands of society, which constantly screams “Do something!”, something that The Abide Guide states is very “un-Dude”; one should just go with the flow.65

Apart from the obvious connection of a form of meditation, what Dudeism and Taoism share is the opinion of why meditation is needed; the stressful, demanding nature of human society. For context, we turn to Welch’s hypothetical Lao Tzu once more.

“’I say to you, your success is failure and your competition drives half your people mad with praise while it drives the other half mad with blame. You justify this by calling it the way to produce the greatest quantity and highest quality of goods and services – as though any goods and services were more important than the people to whom they are supposed to give a happy life, but do not!’”66

This criticism is much in line with Dudeism’s concerns about modern day society, which center on the evils of desire, generally status and wealth.67 The Dude is, through the practice of wu wei in his daily life and through dudeitation, someone who has opted out of the expectations of society without becoming a hermit living alone out in the woods. Happiness and peace of mind are best achieved, according to Dudeism, by not achieving. When life gets stressful, on should dudeitate to calm one’s troubled waters. The Dude does this regularly; dudeitating on his rug while listening to old bowling recordings or dudeitating in the bathtub to the sound of whale-song. It is what enables him to bounce back from the stressful events that occur during the film.

4.5. The Uncarved Block (P’u)

P’u is the Uncarved Block; a piece of wood untouched by the chisel and hammer of society and the world. According Lao Tzu, mankind should return to this original, this natural state; to the state of the Newborn Child (ying erh), when she had fewness of desires (moderation, lack of ambition; no unnatural desires) and knew no morality or aggression. Like Rousseau, Lao Tzu argues that society makes humankind evil. To hold the Uncarved Block is to “know oneself”. The Sage is one who holds the Uncarved Block.68

In Dudeism, the Uncarved Block is mentioned and its mind-set praised, but there appears to be no direct translation. Although it is not as prevalent as the concept of wu wei, Dudeism appears to recognize it as a central feature of the Dude to be emulated. In their own words:

“Since he’s [the Dude] never angling from any fixed position, he can examine each new conceptual element without trying to chisel it into some concrete pillar of belief… Of course, if you questioned every single thing at every moment you’d never be able to get out of bed. A truly uncarved block is as dumb as the proverbial post. The Dude’s method of finding a tipsy balance between open-mindedness and idiocy is just not to care so much about being right all the time.”69

The Dude’s uncomplicated way of thought certainly represents fewness of desires and as evinced above, he is not inclined to aggression. Morality, however, is a trickier question. Those times when the Dude displays some concrete, overt moral sentiment are usually related to Walter. Seeking recompense for his soiled rug; calling Walter out on his behavior; worrying about have caused the death of Bunny; confronting the Big Lebowski about stealing money from the foundation for inner city children. Unlike Walter, however, he is not concerned with being right. Walter constantly asks “Am I wrong?” during the course of the film, convinced of his own point of view and seeking enforce it upon others.

Furthermore, this is in line with Welch’s interpretation of Lao Tzu: society breeds morality in humans, for the benefit of no one, for Lao Tzu means that human nature is inherently good. Someone who holds the Uncarved Block has returned to humanity’s inherently good, natural state. In the words of Welch: “… it is part of man’s nature to feel compassion and because he feels it, not because he wants to do what is right, he will help the man who fell among thieves.”70

Dudeists do acknowledge, however, that the Dude’s actions during the course of the film may not be constantly exemplary. The entire caper is a result of “… Walter’s incessant prodding which impels him [the Dude] to lose his way, to briefly “kidnap himself” as it were.”71

Does Dudeism have anything to add to the idea of the Uncarved Block? In fact it does, for through something called evolutionary psychology an effort is made to justify the principles of the Uncarved Block with the backing of modern science.

As familiar, Dudeism is skeptical of modern society and its influence on humanity’s wellbeing, specifically happiness. It argues that everything from ancient religions to Enlightenment philosophers, modern ideologies like capitalism and socialism or post-modernism have tried to solve this issue of happiness and, ultimately, failed (although some philosophers and religious leader did succeed, temporarily: see Great Dudes of History below).

Evolutionary psychology, however, is apparently some relatively new field of study that holds that humankind was content once, more than 20,000 years ago during the Stone Age. According The Tao of the Dude, evolutionary psychology argues that humanity was content before the invention of agriculture and society; that our brains are still Stone Age brains poorly adjusted for modern society. The Dude is someone who has managed to recreate a Stone Age lifestyle suitable for a more civilized age, because he has learnt how to listen to his brain, which knows best how to make you happy.72

As it is entirely beyond my field of expertise, I will not vouch to the accuracy of this description evolutionary psychology, nor for the field’s validity and relevance. In relation to this study, however, what matters is that Dudeism has made an attempt to modernize Lao Tzu’s

Uncarved Block, for the impetus behind the two ideas appears to be very similar. Welch even writes: “Lao Tzu believed that the evolution of the individual parallels the evolution of the race. In his opinion, the earliest man did not belong to a complex social organization.”73 Although Welch is skeptical of Lao Tzu’s assumption of humanity’s original nature as one free from hostility or aggression, he goes on to provide example of contemporary “primitive” societies that, in his examples, exemplify behavior much like that of the Uncarved Block.74

4.6 The Dude as a Sage and The Great Dudes of History

The Sage is the sum of all the concepts from the Tao Te Ching explained above. He is the one who holds the Uncarved Block, who practices wu wei and who cleaves to the female, to the yin. Consequently, one could suggest that the Dude shares many qualities with the Sage, as the latter is described in the Tao Te Ching.

To reduce the Sage to these mere components, however, would be to do the ideal a disservice. The Sage’s relation to the Tao and his view of the world (and the world’s view of him) could be expounded upon at great length, although it would quickly come to echo previous points. As such, only a few new key points will be brought up here.

Welch describes the Sage with the aid of two verses from the Tao Te Ching.75 In these, the Sage states that “Mine is indeed the mind of a very idiot; So dull am I” and “All men can be put to some use; I alone am intractable and boorish.”76 These are hardly flattering self-descriptions, but they would also seem to apply to the Dude. It is stated by Dudeists themselves that the Dude walks a fine line between open-mindedness and idiocy and he is quite purposely not very useful, i.e. a productive member of society.77

The Dude is the Sage of Dudeism, the example to be emulated if one is to live in harmony with the Tao or the Dude Way. He is not the only Dudeist example of this, however; one of the central ideas within Dudeism is the concept of the Great Dudes of History. Among their ranks, Lao Tzu, Buddha Gautama, Jesus Christ, Mark Twain, Emily Dickinson, Bob Marley, and even Jeff Bridges78 himself can be found.79

The prerequisite for someone to be identified as a Great Dude of History is vague: as the Dudeists say, it may just be your opinion, man. Such examples as have been publically announced, however, have broadly speaking been proponents of peace and happiness who can be interpreted as having lived in harmony with the Dude way. Whether these individuals be deities or mortal human beings, they are usually brought to down to the Dude’s level. This is not to say that they a devalued. Instead, one can consider the Dude’s level to be that of still water: equal and at rest. This necessitates “… stripping away all the halos and heavenly choruses…”, as The Abide Guide puts it.80 To live according to the Dude Way in an exemplary manner is ultimately a very human experience; if nothing else, human examples are easier for other humans to emulate.

Welch makes a similar interpretation of the Sage. In a discussion concerning the Sage’s (a- ) morality, in that he regards humanity with the same ambivalence as Heaven and Earth, Welch reminds us that the Sage himself is a part of humanity: the Sage recognizes that he is not exempt from nature’s kindness or its cruelty.81 This makes the Sage relatable as an example to emulate; it appears to be the same way with the Dude and the Great Dudes of History.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, the main influences on Dudeism come from The Big Lebowski and the Tao Te Ching. Together, the two works are the supporting pillars of Dudeism’s religious history.

Concerning the film, its influence can be likened to a coat of paint; the parlance, the quotes, the characters, and the themes of the film help to mediate the ideas and concepts of the ancient text. While religions are depicted in The Big Lebowski, Judeo-Christian thought takes up more space on the screen than Taoism, for while the Dude can be interpreted as a practitioner, this is never explicitly stated. The particular parlance of the film, such as direct quotes, was originally a hallmark of the fan following, but can now also be found in Dudeism’s religious texts, granting them a special and often comedic flavor.

An important theme of The Big Lebowski is manhood: what makes a man, Mr. Lebowski? Dudeism has adopted the Dude’s answer: a rejection of the American masculine ideal. Instead, Dudeism turns to the Tao Te Ching and its concepts of cleaving to the female, wu wei, the Uncarved Block, Yin-yang, and the ideal of the Sage.

In some cases these concepts have been adapted to fit either our modern times, Western society, or The Big Lebowski, often mediated through various characters (mainly the Dude and Walter) to put theory into practice. The Dude can be seen to embody several of these concepts, albeit it not always to perfection, as Dudeist themselves will admit. In many ways, the Dude can be seen as a very human representation of the Sage in our modern world; Dudeism reflects this by making the Dude its ideal practitioner.

Dudeism represents an exciting new form of religion that marries popular culture, in the form of a cult film, with ancient religious and philosophical concepts. I have no doubt in my mind that this religion has an interesting future both behind and ahead of it.

6. Discussion

Nothing new will be added here in regards to the conclusions of the essay above. This discussion will clarify a few points regarding the process of writing this essay, why certain avenues were not explored, and finally in what areas further research about Dudeism may be conducted.

This essay was supposed to have been written and finished in spring of 2015; due to personal reason, it was delayed and the process was stretched out over summer and autumn. Consequently, it was finished in early 2016. The study suffered from long intermissions in between intense periods of writing as well as what originally was a far too ambitious scope: to not only conduct a comparative study of Dudeism and the Tao Te Ching, but also all its other potential influences. The scope was scaled down and focused in the end, but I would still like to make a mention of the other potential influences, in the interest of future research.

Zen Buddhism is the Japanese form of Chan Buddhism, which originated in China through the meeting of Buddhism and the indigenous Chinese cultures and religions, one of which was Taoism. I believe that a comparative study between Zen Buddhism and Dudeism might yield interesting results, for (in my opinion) Zen Buddhist thought figures heavily in Dudeism. This would, however, also necessitate extrapolating the connection between Chan Buddhism and Taoism. I swiftly found this would make for a digression from the main focus of the essay – Dudeism – and in the interest of time and space this line of research was abandoned and excluded. For anyone interested in examining this further, I would recommend the works of Alan Watts. He was a major influence regarding Western perception of Zen Buddhism during the 20th-century and offers an easy introduction to those not intimately familiar with the subject.

On that note, New Age should be mentioned. The Dude was obviously a product of the 1960’s counterculture and possibly certain New Age elements imported from the East. I found it difficult to identify elements of New Age in Dudeism, which in of itself is not unremarkable. Dudeism was founded in 2005, almost half a century after the decade that saw the rise of New Age. The elements of Eastern thought that are present in Dudeism does not appear to have arisen because of a sudden influx of Taoism into Western culture; rather, it was extrapolated from The Big Lebowski. Unless the definition of New Age has expanded to include new religions based of film and popular culture (such as Judaism), I would not categorize it as such.

Western philosophy is mentioned and quoted at several points in Dudeist literature, Epicureanism makes an appearance, as does various forms of Humanism. The extent of the potential influence has been difficult to ascertain, however, and it was deemed that their inclusion might prove a fruitless digression. Therefor it was not examined at great length.

On a final note regarding other potential influences, language must be mentioned. The Big Lebowski has a very particular parlance and it appears to have shaped Dudeism to a significant extent. Furthermore, Ethan Coen, who studied philosophy at Princeton, wrote his senior thesis on Wittgenstein (whose philosophy focused heavily on language). I am, however, not a linguist, and as such I lack the expertise required to scientifically evaluate the meaning and impact of Dudeism’s distinctive dialect. To include Wittgenstein and the intricacies language would have been far removed from the limited scope of this essay. I have no doubt that the language of Dudeism holds great significance for the religion. Whether or not it will prove a fertile field for meaningful study, however, I cannot say.

This discussion was mainly intended as a means to take a step back and regard the essay from the outside. It was also meant to offer a look back at the process behind it all, as well as a glance forward at areas for future research. It should be noted it is entirely separate from the query and conclusions of the essay above.

Footnotes

1. http://dudeism.com/ http://dudeism.com/

2. The particular parlance of Dudeism utilise specific quotes and/or frequent expressions from The Big Lebowski, often in such a way that anyone not intimately familiar with the film might find it difficult to understand a Dudeist text. In regards to source referencing, Dudeism lives up to its namesake: in the film, the Dude misquotes Cicero as Lenin multiple times. Dudeist literature is somewhat better at sourcing specific quotes; general claims and information, however, is an entirely different matter.

3. Stausberg, Michael, 2012. The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in the Study of Religion. Routledge Ltd, p. 21

4. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ http://www.coenbrothers.net/

5. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/ http://www.indiewire.com/

6. http://www.nytimes.com/ http://journals.cambridge.org/

7. Benjamin, Oliver, 2015. The Tao of the Dude. www.aui.me/press: Abide University. p. 16, 23, 57, 78, 97, 191.

8. Pregadio, Fabrizio, 2008. Encyclopedia of Taoism: Volume I. First published 2008 by Routledge. p. xvi

9. Welch, Holmes, 1966. Taoism – The Parting of the Way – Revised Edition. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 163

10. Pregadio, F., 2008. p. xvi

11. Pregadio, F., 2008. p. 5

12. Welch, H., 1966. p. 88; Pregadio, F., 2008. p. xiv

13. Welch, H., 1966. p. 163

14. Welch, H., 1966. p. 88

15. Pregadio, F., 2008. p. 7

16. http://dudeism.com/

18. http://dudeism.com/

21. http://dudeism.com/takeiteasymanifesto/

22. http://dudeism.com/takeiteasymanifesto/

23. http://dudeism.com/takeiteasymanifesto/ 23 http://dudeism.com/takeiteasymanifesto/

24. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0118715/quotes 24 http://www.imdb.com/ Note: Caps Lock is part of the original quote.

25. http://www.imdb.com/

26. Masciotra, D. “Takin’ It Easy For All Us Sinners: The Dude and Jesus Christ.” Lebowski 101: Limber-minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered. Benjamin, O., ed., 2013. www.aui.me/press: Abide University, p. 45

27. Masciotra, D. “Takin’ It Easy For All Us Sinners: The Dude and Jesus Christ.” Benjamin, O., ed., 2013, p. 46

28. Masciotra, D. “Takin’ It Easy For All Us Sinners: The Dude and Jesus Christ.” Benjamin, O., ed., 2013, p. 44

29. An interesting note: Islam appears at the end of the film, when the Dude wears a shirt with the words “Medina Sod” written on the back. The city of Medina is important and holy to Islam. This is not, however, likely to be an intentional reference.

30. Gooch, C. “What Makes a Feminist, Mr. Lebowski?” Lebowski 101: Limber-minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered. Benjamin, O., ed., 2013. www.aui.me/press: Abide University, p. 151

31. Gooch, C. “What Makes a Feminist, Mr. Lebowski?” Benjamin, O., ed., 2013, p. 152

32. Gooch, C. “What Makes a Feminist, Mr. Lebowski?” Benjamin, O., ed., 2013, p. 152-153

33. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 175-176

34. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 176

35. ”The Way that can be told of is not an Unvarying Way”. Waley, Arthur, 1964. The Way and Its Power – A Study of the Tao Tê Ching and Its Place in Chinese Thought. New York: Grove Press. p. 141

36. “The Tao that can be known is not the Tao”. Church of the Latter-Day Dude, The Dude Ching, p. 13

37. Benjamin, Oliver & Eutsey, Dwayne, 2011. The Abide Guide – Living Like Lebowski. Berkley: Ulysses Press. p. 131

38. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 12

39. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 12

40. Welch, H., 1966. p. 55-58 Welch, H., 1966. p. 79

41. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 12; Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 148

42. Welch, H., 1966. p. 58

43. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 11-13; Waley, Arthur, 1964. p. 162, 165, 183, 186

44. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 12-13

45. Welch, H., 1966. p. 33

46. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 12

47. Dude De Ching, p. 103

48. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 99

49. Waley, Arthur, 1964. p. 151, 197, 224, 238

50. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 100

51. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 101

52. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 14

53. Welch, H., 1966. p. 35

54. Waley, Arthur, 1964. See Chapter I/1; Chapter VI/6; Chapter X/10; Chapter XX/20; Chapter XXV/25; Chapter XXVIII/28; Chapter LII/52; Chapter LIX/59; Chapter LXI/61

55. Waley, Arthur, 1964. See, for the more obvious examples: Chapter VII/8; Chapter XXII/22; Chapter XXVIII/28; Chapter XL/40; Chapter XLIII/43.

56. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 100

57. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 21, 100

58. Welch, H., 1966., p. 169

59. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 109-110

60. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 110

61. Welch, H., 1966. p. 176

62. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 205

63. Welch, H., 1966. p. 33

64. Welch, H., 1966. p. 176

65. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 202-204

66. Welch, H., 1966. p. 167-168

67. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 26-27, p. 54-56, p. 62-63, p. 91

68. Welch, H., 1966. p. 35-36, p. 38-39, p. 41, p. 46

69. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 185

70. Welch, H., 1966. p. 38, p. 46

71. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 100

72. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 91-92, p. 177

73. Welch, H., 1966. p. 35

74. Welch, H., 1966. p. 35-37

75. Welch, H., 1966. p. 48-49; Waley, Arthur, 1964. p. 160, 168-169

76. Welch, H., 1966. p. 48-49; Waley, Arthur, 1964. p. 168-169

77. Benjamin, O., 2015. p. 185

78. The actor who portrayed the Dude in The Big Lebowski.

79. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. P. 77-106

80. Benjamin, O. & Eutsey, D., 2011. p. 78

81. Welch, H., 1966. p. 43-46

Far out, man. Far fucking out!

Like.wow dude

Well, that was really, really fucking interesting, man. Bravo, brother. Bravo.

Jimmy,

This work represents a lot of time, effort and care. And I think you’ve managed to help elevate Dudeism in the direction of more serious consideration as a legitimate religion or way of living. Some Dudeists enjoy the hilarity of the characters, or the laid back notions they represent. Others appreciate the updated takes on Taoism, and the way Dudeism kind of distills those ideals into today’s world. And a few, here and there, help us gain deeper insights and connections to the past through genuinely scholarly efforts. Thanks, man.

Dude,

This is good stuff.

I have, since my teen years, considered the fundamental basics of Taoism, Zen, and essential Yoga philosophy, to be interconnected pillars of common sense living. Many call these things religion, but I don’t. I rather call them ancient psychology and cognitive therapy.