By Barry Popik and Gerald Cohen

Reprinted from Comments on Etymology, October 1998 Vol. 28, #1

Appears monthly October-May; Cost: $13.00 per year (Libraries, Institutions: $17.00 per year)

Edited by Gerald Cohen Department of Applied Arts and Cultural Studies University of Missouri-Rolla, Rolla, Missouri 65401

CONTENTS

1. Etymology of dude finally seems clear

2. Another supposed pre-1883 attestation of dude bites the dust

3. Reprinting of Charles E. Hammet Jr.’s The Natural History Of The Dude

4. Etymology of dude in The Century Dictionary, 1914

5. Dudes as an inexhaustible source of humor: items from the 1880s humor magazine The Hatchet

______________________________________

MORE ON DUDE 2

The search for the elusive etymology of dude–perhaps now successful, at last–has led Barry Popik and me to the broader task of compiling material on the remarkable dude phenomenon of the 19th century.

1. ETYMOLOGY OF DUDE FINALLY SEEMS CLEAR: ‘YANKEE DOODLE DANDY’ PRODUCED A BLEND OF DOOD(LE) AND DANDY TO ‘DOODY’IN SOME NEW ENGLAND TOWNS PRIOR TO 1883; SHORTENED TO DUDE (ONE SYLLABLE) BY 1883.

The key to the etymology of the long troublesome dude lies in the May 1883 article in Clothier and Furnisher, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 27-28—already reprinted in Com, on Et., April 1997, pp. 2-3. Here is that article once again.

‘DEFINITION OF THE WORD DUDE

‘In answer to a correspondent, the editor of the New York Journal of Commerce says that it is impossible to give an “exact definition” of the word “dude” that shall express the various ideas in the minds of those who use it. It is not exactly slang, but has not rooted itself in the language[1] and has not, therefore, a precise and accepted meaning. The word pronounced in two syllables as if spelled “dood-y” has been in occasional use in some New England towns for more than a score of years.[2] It was probably-born as a diminutive of dandy,[3] and applied to the feeble persona-tors of the real fop.[4] It was employed to describe a young man who had nothing particular in him but an alimentary canal, but who was very careful of his exterior adornment, especially in the tie of his cravat, the selection of his watch chain and appendages, the curl of his hair, and the fit of his trousers; one who eschewed not only all useful occupations, but also any violent exercise; who was too languid in his manner to speak with anything but a drawl or a lisp; who affected special refinement, but lacked the chief essentials of manliness. In the last year or two[5] the name, now generally sounded to rhyme with rude,[6] has been applied to one who, in addition to the characteristics we [p. 28] have described, makes a feeble attempt to imitate the manners of some effeminate young nobleman about whom he has read in a foreign novel, but turns out to be only an emasculated penny edition of the despicable character he is trying to copy. The name is doubtless applied in familiar speech and in the press to some who have not all the essential features we have drawn; whatever may be the variations, there is one attribute common to all — they exist without any effort to recompense the world for their living.’

2. ANOTHER SUPPOSED PRE-1883 ATTESTATION OF DUDE BITES THE DUST: THERE’S NO DUDE IN THE 1858ff. THE ADVENTURES OF MR. VERDANT GREEN PRIOR TO 1883.

Dude clearly burst on the scene in Jan. 1883 with the publication of Robert Sale Hill’s poem ‘The Dude,’ and so Popik and I look with great skepticism on any pre-1883 accounts that treat dude as a standard lexical item known to the reading public. Thus far we acknowledge only dude in Mulford 1879.

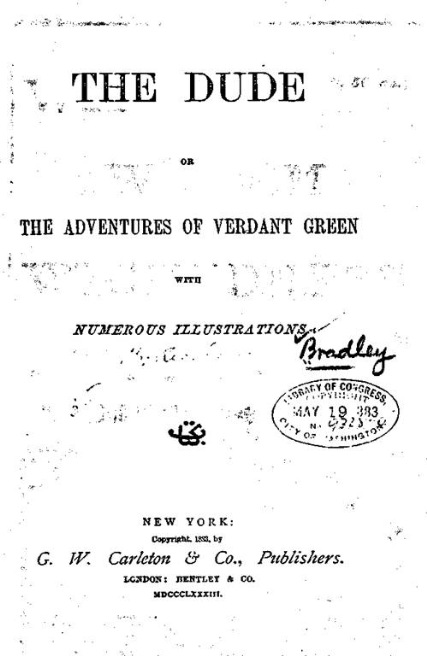

It is now with pleasure that we set aside the supposed pre-1883 attestation of dude in Edward Bradley’s (pseudonym: Cuthbert Bede) The Adventures of Verdant Green, 1858 with later reprint-ings. Volume 1 was also published under the title ‘The Dude, or, The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green,’ and it is easy to get the impression that this title existed already in the pre-1883 printings. For example, WorldCat presents the 1866 edition of The Adventures…, and under the same entry says: ‘Vol. 1 published also under the title: The dude, or, The adventures of Mr. Verdant Green.

It turns out, though, that volume 1 was first reprinted with its ‘The Dude…’ title only in 1883, and the date marked on the Library of Congress copy is specifically May, 1883. Clearly, the publishers were trying to capitalize on the 1883 dude craze by bringing the new term into the title of their book, even though the main character was neither a dandy nor a dude; he was dressed as a young Englishman because he was a young Englishman.

Incidentally, too, I read carefully through volume 1, and the text contains no dude or even dandy.

So, with dude absent in pre-1883 editions of Bradley’s/ Bede’s book, we can set aside the possibility that dude originated in Britain and was imported to the United States. Such a possibility would be very troubling, since the term’s pre-1883 obscurity would be difficult to explain.

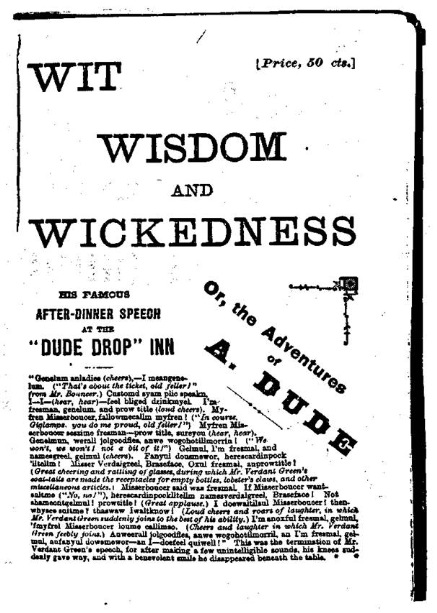

Here now are two pages from Bradley’s/Bede’s book containing ‘Dude’ in the title. Note the 1883 date. And on the second page, note how the publishers play on the dude craze of that year with two puns: ‘Adventures of A. Dude’ and ‘His Famous After-Dinner Speech At The “Dude Drop” Inn.’

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

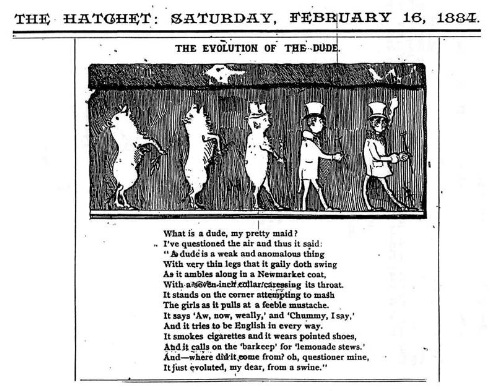

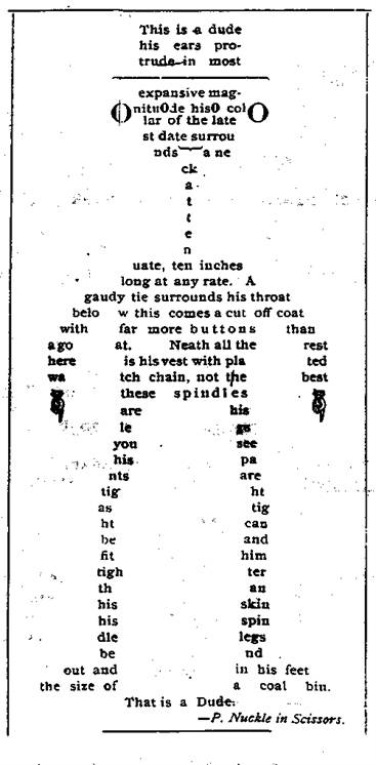

What follows are all from the 1880s humor magazine The Hatchet:

_____________________________________________________

April 5, 1884, p 8/2

TO THE GIRLS.

Flirt with me, play with me,

But don’t be wude,

Wemember I am a

Washington Dude.

_____________________________________________________

April 12, 1884, p. 2/4.

New Name for a Dude.

A theatrical troupe that had been advertised to play “Lady Audley’s Secret” in an Indiana town had among its “artists” a well-defined dude. Inasmuch as nothing of the kind had ever before inhaled the ozone of that particular portion of Hoosierdom, “it” raised great commotion. An old resident, after eyeing “it” closely, asked a bystander what the curiosity was.

“Why,” was the reply, “that’s Lady Audley’s Secret.”

“How do you make that out?”

“Because nobody, with the exception of Lady Audley, knows what it is!”

— Dick Slocum

_____________________________________________________

April 26, 1884, p. 6/3

Navigate to:

Part 1: “Material for the Study of DUDE”

Part 2: “More Material for the Study of DUDE”

Part 3: “More on DUDE”

FOOTNOTES

[1] (B. Popik) my underlining. The remark points to a recent

origin of dude.

[2] (G. Cohen) my underlining. ‘dood-y’ — This points to a connection with dandy, also made directly in the article’s next sentence. ‘occasional use’ — This explains why doody was previously unattested. ‘in some New England towns’ — i.e., the home turf of the Yankee Doodle song. ‘for more than a score of years’ — i.e., well before dude burst onto the scene in 1883.

[3] (G. Cohen) my underlining. ‘diminutive of dandy’ — Yes! But rather thank thinking of a diminutive -oo-, it is better to think of blending, with -oo- coming from Dood(le).

[4] (G. Cohen) my underlining. ‘feeble impersonators of the real fop.’ — This describes Yankee Doodle quite nicely. He was the country bumpkin who stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni; i.e., by sticking a feather in his cap, he imagined himself to be fashionable like the young men of his day known as ‘macaronis.’ Webster III says of macaroni: ‘a member of a class of traveled young Englishmen of the 18th and early 19th centuries that affected foreign ways.’

[5] (B. Popik) No. Make that the last month or two.

[6] (B. Popik) my italics.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.