By Adam Bertocci

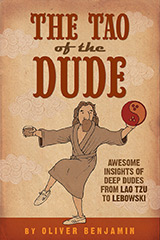

Our pal Adam Bertocci, of Two Gentlemen of Lebowski fame presents a most excellent analysis on what makes a good mashup. What if The Big Lebowski were mashed up with the work of various other authors instead of Shakespeare, perchance? Aye, there’s the rub. To see how it’s done right, go ahead and order his fine book, reviewed in the Dudespaper recently by Sir Chalupa of Lebowskipodcast. You can purchase it here for a modest sum and great rewards. To see how it could be done wrong, read on gentle reader…

There’s an entire cottage industry built around chronicling this, the age of the mashup. Whether we’re putting the lyrics from one song aside the music from another, or stirring together two unrelated movie trailers, or just having a little fun imagining the ‘pop culture clash’, if you will, of two franchises, we are in a thriving age of appropriation. We are a nation of people who enjoy getting peanut butter mixed in someone else’s chocolate.

Two Gentlemen of Lebowski wasn’t the first mash-up project to incorporate The Big Lebowski, nor was it the first to take from classic literature, and it sure as shit won’t be the last on either front. I decided to try and do the next generation’s work for them, and examine a few other authors in the British literary canon through the lens of a certain film. Here’s a few of the great writers across the pond that I don’t think have been given the Lebowski touch… and there’s probably a reason.

1. Oscar Wilde

1. Oscar Wilde

— It is better to be fascinating than to have a permanent income.

— No great Dude ever sees things as they really are. If he did, he would have lapsed in his strict drug regimen.

— All video artists are quite useless.

— Ah! That must be my beeper. Only achievers ever beep in that Wagnerian manner.

— Either that rug stain goes or I do.

Why doesn’t this work? I’m not calling Wilde a nihilist here (his first play aside…), but his trademark flippancy doesn’t gel well with The Big Lebowski. The narrator of the film admires the Dude; Wilde, or so he’d have you think, doesn’t really admire anyone or anything. And when the point of a gag in the film is that, well, life sucks, guess what—Wilde’s already said that.

What does this tell us about the film? A contemporary review of the movie from Andrew O’Hehir at Slate noted a lack of "a cold ironic core", that there was a humanistic tone to the whole thing under the cracks and the technicalities. This separates it from the irony-a-go-go independent comedies of its era and ours, no doubt, but also from Wilde, whose psychic distance from his characters could be measured in kilometers. The movie may sometimes act like it doesn’t care about its characters (if nothing else, consider the undignified hell it puts them through), but it does; the Stranger’s narration is the velvet glove on the occasionally iron fist. Wilde is simply Wilde through and through, and I wouldn’t have him any other way.

2. Charles Dickens

2. Charles Dickens

— The Lebowskis were a very highly achieving family, and a very large family. They were dispersed all over the public offices, and held all sorts of public places. Either Pasadena was under a load of obligation to the Lebowskis, or the Lebowskis were under a load of obligation to Pasadena It was not quite unanimously settled which; the Lebowskis having their opinion, Pasadena theirs.

— "What’s that?" said the Jew. "What do they schedule us on Saturday for? Are those fucks at the league office awake? What have they seen? Speak out, Donny! Quick—quick! for your life."

— "Why do you doubt your senses?"

"Because," said the Dude, "a little thing affects them, man. A slight disorder of the limber mind makes them cheat. You may be an undigested bit of cream, a blot of half and half… There’s more of Kahlua than of corpse about you, whatever you are!"

— For he was dead. There, upon the parking lot outside the bowling alley, he lay at rest. The solemn stillness was no marvel now.

He was dead. No sleep so beautiful and calm, so free from trace of pain, so fair to look upon. He seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God, and waiting for the breath of life; not one who had lived and suffered death.

His receptacle was modestly priced, and here and there some spring skies and green leaves, gathered in a spot he might well have used to favour. "When I die, put near me something that has loved the ocean, up to… Pismo.’ Those may well have been his words.

He was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Donny was dead.

— "I see the Dude who takes it easy for all of us, peaceful, unemployed, unprosperous and happy, in that California which I shall see no more… and I hear him tell the world ‘The Dude abides’, with a tender and a faltering voice. It is a far, far better sarsaparilla that I drink, than I have ever drank…"

Why doesn’t this work? Sentimentality. Not to bring Wilde back into the conversation, but his quote on the death of Little Nell remains the best piece of Dickens criticism I’ve ever read. No less a luminary than John Irving wrote an essay defending Dickensian sentimentality. I suppose Dickens is ripe for parody because of that very aspect, and you could probably have a lot of fun with it, but it wouldn’t quite fit, I don’t think. I’m not a sentimental creature myself, and I don’t think most people were, by the ’90s. This is why every sitcom that’s ever done a Christmas Carol episode just embarrasses themselves, except Black Adder.

What does this tell us about the film? It cares, but it doesn’t expect the universe to. Donny dies, but life goes on, Walter ruins the solemnities in a hoary old gag and even the Stranger, while he "didn’t like seeing Donny go," recognizes its place in the "whole durned human comedy."

3. C.S. Lewis

3. C.S. Lewis

— "And I say also this. I do not think the bowling alley would be so bright, nor the Caucasian so cold, nor coitus so sweet, if there were no nihilists under the bridge."

— We want, in fact, not so much a Father in Heaven as a grandfather in heaven—a senile benevolence who, as they say, "takes ‘er easy for all us sinners" and whose plan for the universe was simply that it might be truly said at the end of each day, "the Dude abides".

— "Are the nihilists fascists?"

"Oh no, Donny. What would become of us if they were?"

— Friendship arises out of mere companionship when two or more of the companions discover that they wish to enter a league game. The typical expression of opening Friendship could be something like, "What? You too? I thought I was the only one who couldn’t roll on Saturday."

— Once there were four bowlers whose names were Walter, Donnie, Jesus and… one called the Dude. This story is about something that happened to them when they were in California during the war against the camel-fuckers.

— When he had got to the last reel and come to the end, he said, "That is the most stupefying story I’ve ever heard or ever shall hear in my whole life. Oh, made me laugh to beat the band… It was about a bum and a rug and a ringer and a goldbricker, I know that much. But I can’t remember, and what shall I do?"

Why doesn’t this work? I know there’s an entire book on the matter, but I’m not sure I can reconcile Christianity with the philosophical viewpoints expressed in the film.

What does this tell us about the film? There’s ample room in the tradition of pop culture imparting the lessons of religious movements. I consider The Big Lebowski a worthwhile pop primer on Eastern religion, a gateway drug, if you will, and I’m not alone; Dudeism has used it to expound on the Tao Te Ching and Taoism. I imagine that C.S. Lewis was most kids’ first Christian allegory. I wonder how many college kids learned about some kinda Eastern thing from The Big Lebowski.

4. J.R.R. Tolkien

4. J.R.R. Tolkien

— On line at a Ralph’s there stood a Dude.

— "I wish it need not have happened on my rug," said the Dude.

— "Freely meddle in the affairs of nihilists, for they are amateurs and quick to fuck up."

— "I wonder if we shall ever be put into songs or tales… read out of a great big book with red and black letters, years and years afterwards. And people will say: ‘Let’s hear about the Dude and his rug!’ And they’ll say: ‘Yes, that’s one of my favourite stories. The Dude was very lazy, wasn’t he, dad?’ ‘Yes, my boy, the laziest in Los Angeles County, and that’s saying a lot.’"

Why doesn’t this work? The old saw of treating something small and blowing it up to epic proportions probably needs a rest. Casting the Dude in the hobbit mold is cute, but the consciously high style of Tolkien’s world is at odds with the calculated no-style style of Dudely verbiage.

What does this tell us about the film? Nothing you didn’t already know, I suspect. No, the way to do this right would be to cast Lewis and Tolkien (friends not above a little bickering and private dispute) as the Dude and Walter and get them into an argument about each other’s fantasy stories.

5. Brontë sisters

5. Brontë sisters

— "I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and tore my mind; they’ve gone through and through me, like vodka through Kahlua, and altered the condition of what condition I was in."

— "I can so clearly distinguish between the Chinaman and his crime; I can so easily declare the first not the issue while I abhor the last."

— Reader, I abided.

Why doesn’t this work? Can you reconcile a female voice with the decidely male atmosphere of the film? There’s only two women of note in the movie, one a weird parody of feminism and one so far from the idea as to make no odds. Where’s the voice of reason? Would a proper English lady stand for flashing a piece on the lanes?

What does this tell us about the film? It’s a man’s world, and maybe that’s why everyone keeps fucking up. The Dude may hold women at arm’s length, but he might have done well to feminize his life a bit, maybe invite one onto the bowling team.

6. William Wordsworth

6. William Wordsworth

— I wandered lonely in the Ralph’s…

— The world is too much with me; nihilists

Believing in nothing have laid waste my rug:

Little I see in Nature that I’ve dug

As much as that rug washed away; a sordid piss!

Why doesn’t this work? It almost could; I think some of Wordsworth’s melancholy is echoed in the weariness of our protagonist. There’s an anecdote that he had concerns about being named Poet Laureate, until Robert Peel assured him that he would not be made to produce anything. Maybe Wordsworth’s feelings on achieving had taken a decidedly Dudely turn in the very height of his achievement.

What does this tell us about the film? Some call Wordsworth a metaphysical poet, but the Dude’s generation had broader meanings for the term. Evidently even being metaphysical was exhausting before the 1960s.

7. P.G. Wodehouse

7. P.G. Wodehouse

(I must pause here. Oh, if I had to, I could probably knock together a funny little series of quotes about ‘vodka and K.’ and ‘what ho, nihilist’ trying to escape an engagement with Maude and the Dude giving up his rug because Walter disapproves of it… but, you know what, I just don’t want to. I wasn’t afraid to tackle Shakespeare, but imitating Wodehouse is a man’s game, and even for the sake of bad parody, I’m just not up to it.)

Why doesn’t this work? You’re combining one stylized text with an author whose style defies containment. It would be like two shockwaves crossing and reinforcing each other, with a subsequent explosion and possible rift in the space-time continuum.

What does this tell us about the film? The filmmakers like to drag their characters through the mud, really make their lives difficult and plagued with obstacles; Wodehouse, by contrast, wrote of an idealized, idyllic England that never existed any more than the idealized 60s the Dude is stuck in existed. Are there issues of economic and social class in The Big Lebowski? Bertie Wooster is no less a slacker than the Dude, but he has the money to do so. What if both Lebowskis in the film had been millionaires, and the protagonist’s rug was all the more valued? Would he have laughed off the problem, or pursued the issue on the grounds of checking aggression? In short—are the Dude’s problems worse because he is so poorly off, or does he only make them worse because he’s the kind of unemployed bum who has time to pursue this shit to the bitter end?

8. William McGonagall

8. William McGonagall

— Beautiful rug that tied together my room

Alas! I am very sorry to fume

That you were pissed on to your ugly doom

On September 11th of 1991

Which shall be remembered as not much fun.

Why doesn’t this work? Have you actually read this guy’s stuff?

What does this tell us about the film? Nothing, but it tells me something about the art of writing: it’s easier to imitate a good writer than a bad one. That’s sort of a relief, actually.

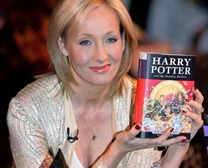

9. J.K. Rowling

9. J.K. Rowling

I’m sorry, I’m not touching this with a ten-foot pole.

Well, I think we’ve all learned something. Maybe you can’t really just mash up anything with anything. I’m just relieved no one tried to make me explain James Joyce.

Love it!

Great Literature review. Very heavy indeed. I need an oat soda about now….